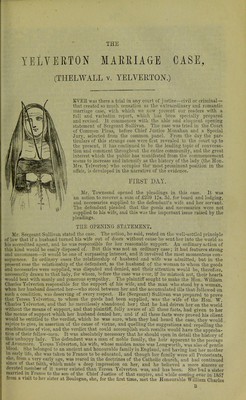

The Yelverton marriage case : Thelwall v. Yelverton : comprising an authentic and unabridged account of the most extraordinary trial of modern times, with all its revelations, incidents and details : specially reported.

- Avonmore, William Charles Yelverton, Viscount, 1824-1883.

- Date:

- 1861

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The Yelverton marriage case : Thelwall v. Yelverton : comprising an authentic and unabridged account of the most extraordinary trial of modern times, with all its revelations, incidents and details : specially reported. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by Royal College of Physicians, London. The original may be consulted at Royal College of Physicians, London.

14/198 page 10

![Telverton. Their acquaintance was of a most passing and fonnal character, and the slightest incident in that journey led to a friendship which relined into love. When she reached London her sister, Mrs. Bellamy, whose husband lived at Abergavenny Castle, in Wales, delayed going or sending to meet her on tho arrival of the steamer, and the Honourable Mr. Telverton, seeing her alone, volunteered his assistance, and called a cab for her, in which she went home. In a day or two afterwards Major Telverton called at her sister’s house and paid his respects, and nothing followed except the interchange of civilities. In 1853 Miss Teresa Long- worth was sent to complete her studies in the south of Italy, for she was a most accomplished woman, and being in Naples, and being desirous of sending a letter to a cousin, who was a Eoyal Commissioner at Montenegro, she was told by a banker at Naples that it would be necessary to have her letters sent to Malta, to be re-posted, and he volunteered to send her letters to his cousin through a friend of his, an officer in Malta. The officer was Captain, now Major, Telverton. This small circumstance led to a correspondence, spread over many years, between the Hon. Major and Miss Longworth, without either laying eyes on the other during the time the correspondence continued; yet letter after letter passed betw'een them, displaying on the face of them great afl'ection, couched in terms of the most Platonic endearment. Miss Longworth retumod from Italy to Franee in May, 1855. They' would all remember the interest that was excited by a baud of heroic women leaving England and France, and volunteering their miuistering ;ud in the hospitals of the Crimea. From France there went a body of the Sisters of Charity, and they associated with themselves ladies of rank in France, who accompanied them, without vows, on the mission of mercy. One of this band was Teresa Longworth. At the time she left France to go to the Crimea, Major Telverton was on his way from the Crimea, where he had been serving as an officer of artillery, to England, and did not retvun to the Crimea until September, 1855. Miss Longworth remained for five or six months at the hospital at Galata, and when Major Telverton returned he found her out, and visited her, and that was the first time he had seen her since he saw her in her sister’s house in 1852. He then professed an ardent attachment for her, and asked her to marry him. She assented, and agreed to leave the occupation at which she was employed to become his wife, but he accompanied his pro- posal with a proposition to which she could not assent—that it should be a secret marriage, cele- brated there oy any priest whom he could find. Consequently the marriage was defeired until they should arrive in England. An armistice took place in the Crimea, and Miss Longworth, who always moved in the first society, was invited by the wife of one of the general officers of the British army on a visit to the Crimea. She went, and during her stay of five or six weeks, the Hon. Major Telverton was constant in his visits. He renewed his professions of attachment and offers of marriage, and spoke of the happy times in store for them in England ; and so “ court- ship’s smiling day” passed off. When m-ging the secret marriage. Major Telverton suggested that they should get married by a Greek priest in one of the churches of Balaklava, and he said that a Greek priest was as good as a Catholic priest; but she was firm in her resolve—her moral principle and sense of religion were so strong, that no inducement could make her yield from her determina- tion that a priest of that religion wnich she professed should unite her in marriage. The reasons which the defendant gave for deshing a secret marriage were, that in circumstances he was not very well off; that he had an uncle on whose bounty he very much depended, who would be annoyed if he married, but he vowed to her that nobody but she should be his wife. Miss Long- worth returned to England in the autumn of 1866, and went on a visit to her sister in Wales, where she remained until February, 1857. From that she went on a visit to Edinburgh, where she moved, as she always did, in the first society. She was then a lovely and accomplished girl; he believed as lovely a woman as ever breathed the breath of life. They should not expect to see her so now. She was changed. Her cheek was paler and thinner than it-should be for one so young. She had gone through years of sufi'ering which a soul of heroism alone could endure, and when they had heaid her story from herself, they would ask themselves how great must have been her mind, how fresh the sense of her own character, to enable her to bear up against the infamous treatment to which she had been subjected. Major Telverton was stationed at Leith in 1867, and the moment he heard of her arrival in Edinburgh he renewed his visits to her and bis vows as be- fore. He laid before her the reasons why she should accede to his wish about the secret marriage. He told her that a Catholic priest in Scotland could be got to marry them, and there was no reason why she should not agree to it; that other women had done the same before, and that there was no breach of morality in it. But she was firm in her resolve. She refused to agree to a secret marriage. Everything that influence and artifice could do—everything that man could do he did to persuade her to be married in secret, but she refused. On all occasions he professed himself a Boman Catholic to her. Ho attended with her the celebration of mass in a Catholic cluipel in Edinburgh, and she always urged-upon him that it would be a violation of his opinions, as a Catholic, to have a secret marriage, but his proposal always was a secret marriage or a postponement of the ceremony. He (Sergeant Sullivan) would say, from looking through the coires])ondence of tho parties, that notions of dishonour Lad not, pernaps, token root in the mind of Major Telverton—that he had not for his object the ruin of the lady'. On the contrary, tho correspondenco would lead to tho belief that his feelings towards her were those of a gentleman and a man of honour at the time. At this time an incident occurred in Edinburgh te which ho would ask the attention of the jury. Having proposed the secret marriage, and urged it, he, in April, 1867, induced her to hear him read tbo marriage ceremony from a Church of England prayer book in tho house of a Mr. Gamble, at Edinburgh, llo told her that, by tho law of Scolliind, marriage by a priest was not neccssarj—that mutual consent and promise made](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b28408214_0014.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)