Report on the mortality of cholera in England, 1848-49.

- Farr, William, 1807-1883.

- Date:

- 1852

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Report on the mortality of cholera in England, 1848-49. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by Royal College of Physicians, London. The original may be consulted at Royal College of Physicians, London.

20/506

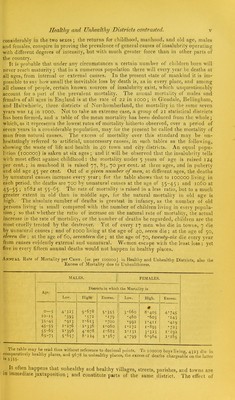

![typhus, small-pox, influenza, and other zymotic diseases. The writings of Mead, Pringle, Lind, Blane, Jackson, Price, and Priestley,—the sanatory improvements in the navy, the army, and the prisons,—as well as the discovery of vaccination by Jenner,—all conduced to the diffusion of the sound doctrines of public heaiili, and had a practical effect, which, with the improved condition of the poorer classes, led to a greatly reduced mortality in the present century. Since 1816 the returns indicate a retrograde move- ment. The mortality has apparently increased. Influenza has been several times epidemic, and the Asiatic cholera reached England, and cutoff several thousands of the inhabitants in 1832. It reappeared and prevailed again, as we have seen, with no miti- gated violence, in 1849. The health of all parts of the kingdom is not equally bad. Some districts are in- fested by epidemics constantly recurring; the people are immersed in an atmospliere that weakens their powers, troubles their functions, and shortens their lives. Other localities are so favourably circumstanced that great numbers attain old age in the enjoyment of all their foculties, and suffer rarely from epidemics. The variations in the mortality are seen in'ihe Tables (pp. cvi-cxxvii), which have been extracted and arranged from the Nintii Annual Report. The rate of mortality is calculated on 2,436,648 deaths in the 7 years, 1838-44; and on the population taken at the Census of 1841, in the middle of the period. On tracing over 324 sub-divisions of the country, the force of deatli in males and females of different ages, the most remarkable differences are discovered. Here of 1000 young children under 5 years of age forty die, there a hundred and twenty die anntuilly; here, of 1000 men of mature age (35-45) nine die, there nineteen die yearly; of 1000 men of 45-55 years of age twelve die in one district, thirty in another; at the more advanced ages of tlie ne.\t decennium (55-65) twenty four die anniuiUy in one, f/ty in another district: of 1000 females of all ages without distinction, 14 die aniuially in three districts, 15 die in eigliteen districts, 17 (or less) in Ibriy-eiglil districts. And in strong contrast, 23 in 1000 females die in twenty districts, 26 in 1000 in three districts, 27 in seven districts, 31 in two districts. The mortality at all ages, without distinction, differs much less than the mortahty of children, and less even than the mortality of men and women of the age of 35 and upwards in the several parts of the country. The population from the age of 15 to 35 is unsealed ; at that age the emigration of servants and artizans from the country to the towns takes place; and as consumption, the disease then most fatal, is slow in its course, its victims in many cases retreat from the towns to their parents' homes in the villages to die. And the death is registered where it happens, not where the fatal disease begun, so that, on comparison, it is told twice in favour of the towns; once in being withdrawn from the town register, and a second lime in being added to the country register, to which it does not properly belong. Independently of external causes, and by the force of a natural law, the mortality varies at different periods of life: so that'the rate of dying in two mixed popula- tions may differ according to the varying proportions of children, young persons, or old people. The series of tables (pp. cxii-cxxvii) shows the rate of mortality at six periods of life, under five years, at 10-15, 35-45, 45-55, 55-65> and 65-75. shown in the extreme cases, that when the general mortality is either high or low, the mortality at nearly all these ages is high or low; and a collation of the whole leaves little doubt on the question of ihe relative insalubrity of the various parts of the country. Upon looking generally at the health of the population, it will be tbund tliat people suiTer most in the great town districts. Liverpool and Manchester are the places of highest mortality, then follow some of the districts of London, Merthyr Tydfil, Bristol, South Shields, Macclesfield, Hull, several districts of Lancashire, Shefiield, Nottingham, Leicester, Stoke-upon-Trent, Wolstanton and Burslem, Leeds, Newcastle-on-Tyne, Birmingham, Coventry, Wolverhampton, Newcastle-under-Lyme, Derby, Salisbury, ]yorthampton, Bradford, Gateshead, Shrewsbury, Walsall, Norwich, Colchester, Sun- derland, E.xeter, Worcester, Bedford, Dudley, Bath, Ipswich, Carlisle, Lancaster, Cambridge, Aylesbury, Maidstone, Canterbury, Wycombe, Gloucester, Wakefield, and Kcading. , The mortality is not increased equally at every age iti these districts. And it vanes](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b24751297_0020.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)