Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Essays / by James Wilkes [and] William Hammond. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. The original may be consulted at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

32/66 page 32

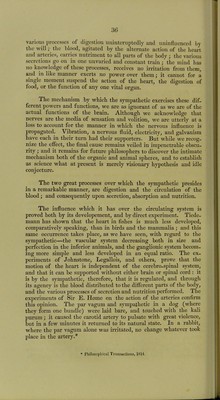

![a. i). 1801—The first who took up, and assumed to himself, the theory established by Johnstone, was Bichat, according to whom the whole system ascribed to organic or nutritive life, is nothing but a congeries of insulated centres independent of each other, from which the different organs receive nervous energy. The anatomical difference between organic and animal nerves, he defines to be this—that the latter have a common centre, the brain; the former, many centres, the ganglia: these are connected together by the intervention of branches, and what is termed the trunk is merely an anastomosis, or series of nervous communications, and not as is generally supposed, a nerve proceeding from the brain or spinal cord.^T He adduces the following arguments to prove that it is not a nerve of the same description as others, but only a series of anasto- moses: 1st. That the communications are frequently interrupted, without any effect on the organs supplied: thus, he says, a dis- tinct interval is in some instances observed between the pectoral and lumbar portion of this nerve. (Weber, Portal, and Lobstein, however, affirm that they never saw it interrupted in its course, though on superficial examination it sometimes does appear so.) 2nd. That the opthalmic and spheno-palatine ganglia are constantly found in an insulated state, and that they communicate by means of their branches with the cerebral nerves only. 3rd. That in birds, as Cuvier has ascertained, the superior cervical ganglion is always found insulated, never communicating with the inferior. The investigations of Tiedemann,* Emmert,+ and Meckel,^ how- ever, prove that this idea is incorrect, that in birds there always does exist a communication with the 1st cervical ganglion. This theory was improved upon by Reil,H according to whom, the sympathetic nerve constitutes a system totally different from the cerebral. It belongs only to organs of nutrition, presides over function alone, and by its assistance things lost and consumed by the process of life are re-produced, wherefore it is rightly called the nervous vegetative system. In the more perfect classes of animals, it is intimately connected with the cerebral or animal nervous sys- tem, but yet in no degree is it produced or emanates from it. The cerebral and ganglionic systems essentially differ from each other: ] st, in the branches of the former running to the brain, and there becoming rooted, which is therefore the central system: 2nd, in the ganglia having no one focus of action, but being widely diffused. He considers the use of this great series or chain of ganglia to be the following—1st, that the power of the will on internal or- gans and those pertaining to animal life may be lessened. 2nd, that the “ pathemata” or internal impressions which the vital pro- * Bichat, Anatomic Generate. Translated by Constant Cofl'yn, v.i, p. 241. + Zoologie, b. 2, p. 44. X Archiv. fur die Physiologic, b. 11, p. 117. V Manuel d’ Anat., 1.1, p. 256. II Archiv. fur die Physiologic, p. 189.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21727892_0034.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)