The evolution of man : a popular scientific study / by Ernst Haeckel. Translated from the 5th (enl.) ed. by Joseph McCabe.

- Ernst Haeckel

- Date:

- 1905

Licence: In copyright

Credit: The evolution of man : a popular scientific study / by Ernst Haeckel. Translated from the 5th (enl.) ed. by Joseph McCabe. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by The University of Leeds Library. The original may be consulted at The University of Leeds Library.

316/392 (page 290)

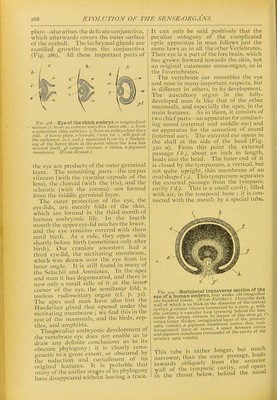

![pit-like depression in the skin. At the biick part of the liead at hotli sides, near the after brain, a small thickening of the horny plate is formed at the upper end of the second gill-cleft,(Fig. 322 A JI). This sinks into a sort of pit, and severs from the epidermis, just as the lens of the eye docs. In this way is formed at each side, directly under the horny plate of the back part of the head, a small vesicle filled with fluid, the primitive auscultory vesicle, or the primary laby- rinth. As it separates froni its source, the horny plate, and presses inwards and backwards into the skull, it changes from round to pear-shaped (Figs. 322 B Iv, 323 0). The outer part of it is length- ened into a thin stem, which at first still opens outwards by a narrow canal. This is the labyrinthic appendage (Fig. 322 Ir). In the lower Vertebrates it developes into a special cavity filled with calcareous crystals, which remains open permanently in some of the primitive fishes, and opens outwards in the upper part of the skull. But in the mammals the labyrinthic appendage degenerates. In these it has only a phylogenetic interest as a rudimentary organ, with no actual physiological significance. The useless relic of it passes through the wall of the petrous bone in the shape of a narrow canal, and iscalled thevestibularaqueduct. It is only the inner and lower bulbous part of the separated auscultory vesicle that developes into the highly complex and differentiated structure that Is after- wards known as the secondary labyrinth. This vesicle divides at an early stage into an upper and larger and a lower and smaller section. From the one we get the utricuhis with the semi-circular canals ; from the other the sacculus and the cochlea (Fig. 320 c). The canals are formed in the shape of simple pouch-like involutions of the utricle (cse and csp). The edges join together in the middle ]Dart of each fold, and separate from the utricle, the two ends remaining in open connection with its cavity. All the Gnathostomes have these three canals like man, whereas among the Cyclo- stomes the lampreys have only two and the hag-fishes only one. The very com- plex structure of the cochlea, one of the most elaborate and wonderful outcomes of adaptation in the mammal body, developes originally in very simple fashion as a flask-like projection from thesacculus. As Hasse and Retzius have pointed out, we find the successive ontogenetic stages of its growth represented permanently in the series of the higher Vertebrates. The cochlea is wanting .even in the Mono- tremes, and is restricted to the rest of the mammals and man. The auditory nerve, or eightli cerebral nerve, expands with one branch in the cochlea, and with the other in the remaining parts of the labyrinth. This nerve is, as Gegenbaur has shown, the sensory dorsal branch of a cerebro - spinal nerve, the motor ventral branch of which acts for the muscles of the face (nervus facialis). It has therefore origi- nated phylogenetically from an ordinarj' cutaneous nerve, and so is of quite different origin from the optic and olfactory nerves, which both represent direct outgrowths of the brain. In this respect the auscul- tory organ is essentially different from the organs of sight and smell. The acoustic nerve is formed from ectodermic cells of the hind brain, and developes from the nervous structure that appears at its dorsal limit. On the other hand, all the membranous, cartilaginous, and osseous coverings of the labyrinth are formed from the mesodermic head- plates. The apparatus for conductmg sound which we find in the external and middle ear of mammals developes quite sepa- rately from the apparatus for the sensa- tion of sound. It is both phylogeneti- cally and ontogenetically an independent secondary formation, a later accession to Fig. 122.—Development of the auscultory labyrinth of the chick, in five successive stages (A-E). (Vertical transverse sections of the skull.) fl auscultory pits, Iv auscultory vesicles, Ir labyrinthic appendage, c rudi- mentary cochlea, csp posterior canal, cse external canal, jv jugular vein. (From Reissner.)](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21508616_0316.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)