Reprints of articles contributed to medical journals, 1895-1909 / by John D. Gimlette.

- Gimlette, John D. (John Desmond), 1867-1934

- Date:

- 1911

Licence: In copyright

Credit: Reprints of articles contributed to medical journals, 1895-1909 / by John D. Gimlette. Source: Wellcome Collection.

159/160

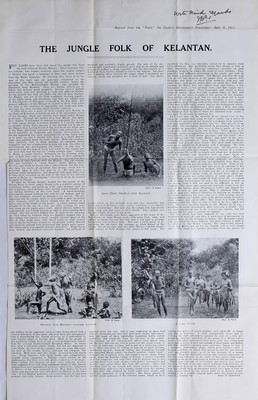

![/Reprint from the lA/ifc **£- ‘Field, the Country gentleman's Newspaper.—Sept. 9, 1911. THE JUNGLE FOLK OF KELANTAN. EEW TALES have been told about tho people who form the wild tribes of British Mulaya. These timorous folk j aro outcasts, who wander restlessly about the mighty jungles of Malaya and speak a language of their own, quite; distinct I from the Malay language. By tradition they claim to be the men of tho land, and aro generally recognised as the j aborigines who fled, during tho twelfth century, before the | advance of tho Mohammedan Malays who invaded the Peninsula from Malacca. They arc known collectively ns Sakai, but without much propriety, because several distinct tribes exist, each still speaking a crude nnd different dialect. At tho present day they arc under the heel of their masters, tho Malays, and are so shy from constantly herding together in tho silent woods and mountains that they are seldom seen bv tho majority of European residents in tho Far East. Tlfc general influence of tho Malays in regard to these wild tribes has boon in the direction of oppression, but trade and inter- marriage has often brought about friendly relations. A littJo while ago a party of them oamped nour Serosa, in the Stnto of Kelantan, a station on one of the up-country rivers of tho territory which has recently been taken under British protection. Through tho agency of a local Malay, who spoke their dialect, I succeeded in making arrangements for a visit to their camp, though it seemed doubtful if I should succeed in actually seeing them, because it was pointed out to me by the Malays that, having heard of tho arrival of tho white men in tho State, and being conscious of their own inferiority, they would naturally be suspicious and fearful. Nevertheless, on the day appointed two aged representatives of the Sakai came in to greet us, and I started with them in a small dug-out canoe and paddled down the main stream. Both old creatures were partially clad in dirty sarongs, or coloured cotton wrappers; one was a cadaverous-looking old man, the other an evil-fnvoured but well-meaning old woman. It was easy to recognise from the mop of frizzy hair worn by the woman and her dark skin that she was an *' orang pangan utan, ’ literally in Malay a jungle dweller, belonging to the Semang tribe, and, as both were clad in sarongs in place of their customary apron of leaves or girdle of bul k, it might be surmised that they had been in close contact with the Malays. The old woman, ■who was evidently a “ tame Snkai,” spoke Malay fairly fluently, nnd could be drawn into n conversation, but the man, who bore tho marks of privation and disease, could not be prevailed upon to take any part in it. He only gave a , guttural grunt occasionally, and shivered with ague from time to time as he crouched on the seat of the boat in the attitude known in Malay as “ melengong,” literally to sit on tho ground ■■yrappod in thought. At noon wo turned sharply, headed for tho mouth of the Serasa River (a small jungle stream with a grateful canopy of greenwood shade), and poled up it for some distanoo until we met a stalwart, dark-skinned, curly headed young Pangan, who was felling bamboos on the river bank. A weird-sounding conversation ensued between him and the old woman, and the boy was evidently directed to announce our arrival. Ho dis- appeared into the jungle, while we proceeded to pole up stream more leisurely, until we finally landed near the trunk of a fallen tree in'tho depth of tho forest. A rather tedious climb : brought us to tho lop of a hill, and after groping for some way along an old jungle game track, almost entirely hidden by undergrowth, our friends warned us that we were nearing their village; this was so well hidden that, in spite of tho warning, wo were taken by surprise when wo suddenly stepped into it. The village was merely a small, roughly cleared space at tho : foot of some giant trees, with about seven or eight rickety lean-to booths carelessly erected on the ground, roofed, floored, and partially inclosed with brushwood and jungle palm loaves. Tho wholo aspect was squalid, desolate, and dirty. About thirty j men, women, and children clustered together nnd jabbered to accepted tracted little novelty of boxful of The sobs of the dis- way to the delight and and the distribution of a tho tension ; but there when I produced my of gun. The photo- [Phot: R. Portot. Sakai Chief Shooting with Blowpipe. graph' taken on this occasion were not very successful, but others taken in Kelantan undtr similar conditions serve equally well as illustrations. Tho next day the jungle folk had struck their camp and had gone further inland. They seldom stay for any length of time in one place Shortly afterwards some Sakai appeared at the house of the Toh Kuen, or looal Malay chief, with some fruit, reein, and rattans to barter for rice and salt, and it was easy to arrange for another visit to their camp. This time a small party of us, including the toh kuen, the pawang, or witch doctor of tho village, two of my men, nnd two other Malays, started shortly after sunrise to walk through the jungle to the camp. Tho unsettled life they aro constantly called on to excrciso from early childhood. The perfection which they attain, as well as their capability of enduring continued exertion on long journeys, seems to bo simply the result of early training. They generally lind sufficient subsistence in the jungle, and lead on tho whole a peaceful existence. The Malays suid that tho wild men go out and disperse in the jungle daily at sunrise, with blowpipes and darts, to shoot birds, monkeys, wild pig, und small game, such as tho mouse deer, on which they feed after roasting; the flesh; they nlso collect frogs and snakes, a few nourishing fruits, a few salutary roots, und thus sujjply their most immediate wants. They reassemble and return to their camp at sunset, when fires are kindled cither by flint and steel or by tho cross friction of two pieces of dry bamboo. They neither rob nor steal, but arc said to cheat and to have no form of worship. The marriage ceremony is very simple, nnd consists in plighting troth before their chief, who inquires if tho man is sufficiently armed, and on the bridegroom satisfy- ing tho Ichief that ho possesses a blow pipe, a flint, and some form of iron chopper, nothing further is necessary, except (among llio Semhng) that ho has to chase his intended bride round a treo until ho succeeds in catching her. As I have said, on the occasion of my second visit to tho j Sakai wo reached their camp to find it empty, but a series of I howls by tho pawang at last brought a response from someone, who had apparently been hiding near by. This proved to bo tho chief, who eventually succeeded in persuading the rest of his peojilo to assemble; they were a family party of six or seven men, with their wives and children These people were Semang, similar in appearance to tho aborigines at Sorasa, but moro healthy, of much better physique, and less timid ; they wero clothed like tho rustic Malay, nnd most of the men, following tho example of “ tamo Sakai,” who imitate Malay customs,! had shaved their heads. The chief good naturedly gavo us an exhibition of shooting with a blowpipe. He shot at a target with pellets of hardened resin. All tho tribes are very proficient, with this weapon, which consists of a hollow bumboo about 7ft. or 8ft. in length nnd about iin. in diameter, perfectly l straight, and furnished with an inner lining of Immlx ? and n small wooden cup as a mouthpiece. Many of tho blbwpipes are decorated with patterns in carving. Poisoned darts or balls of clay are propelled from them by means of tho breath nnd the help of a hit of pith. Some of the other tribes use a primitive bow and arrow in addition to the blowpipe. This is a powerful wenpon, with a shaft made of | iron wood about 2 yards in length nrd 2in. in breadth at the I widest part, and a string made of twisted bark about £in. [ thick. Tho arrows are either wholly of wood, spear shaped, with a blade of 4in. and length of shaft about 3ft., or tipped with a rough barbed piece of iron. The poisoned wounds of (ivo arrows from a bow aro said to be sufficient to kill an elephant. The darts and arrows aro generally made from tho stem of tho bertam palm (Euycissomi tristis) and dipped for I nearly an inch in ipoh poison. This is obtained from the I ipoh or upas tree (Antiaris toxicaria) by making an incision in tho trunk, collecting tho juice, and (it is said) mixing various ' other poisonous ingredients, such as the poison glands of snakes, white arsenic, and putrid offal. Tho result is a black, sticky I substance, and tho . licet on man is said to bo very rapid and fatal. Tho onlv antidote known to the Malays is to eat a mouthful of earth immediately after receiving a wound. Tho toh kuen considered this to be a sovereign remedy, but the pawang did not care to express an opinion. Tho awe which had been inspired by our visit was now beginning to wear off. and after a good deal of persuasion we induced some of tho Semang to dance. The Kelantan jungle folk are noted for their dancing, but their singing is held to bo inferior to the Malay singing. Tho improvised nnutch, which was finally got up for our benefit, was a very simple affair. The band was quickly provided from tho jungle by Shooting with Blowpipe—Another Attitude. ono another on my approach, while a little brown dwarf with a hideous deformity of tho spine, who had been left unsupported near a smouldering fire, wailed in terror as if confronted by some fearful ghoul or foreign devil. Most of the people in this primitive village were as tall as but perhaps more comely than tho average brown-skinned Kelantan Malay. In colour they were a decidedly dusky brown, but did not approach a sooty black ; tho hair of the younger men was crisp and curly, but that of the women frizzly, although not compact like nstrakan. Both sexes had fine, bright, forward-bearing brown eyes. These features, with large hands and comparatively straight noses, suggested a Papuan origin similar to the Andamanese, but there were also points suggestive of the negro. Many—indeed, the majority of them—were suffering severely from malarial fever and from loathsome forms of skin disease. Among these were examples of a disease called yaws, indigenous to Africa; it has been conveyed to the West Indies by negro slaves, nnd perhaps has been introduced to Malaya in the same way. A few English medicines were soon disposed of. and some presents (red cloth, tobnoco, cheap mirrors, nnd the like) were pawang knew tho way, and it was reassuring to have him with us; these men are generally intelligent, handy individuals, who get much of their knowledge regarding herbs, native medicines, and woodcraft from the dwellers in the jungle. Our pawang, an old, white-haired, active little brown man, led tho way, nnd was the first to point out tho recent tracks of a tiger, to scent some wildpig, and to put up a clattering jungle fowl. After two hours of wading in and out of small streams, clambering up hills, slipping, sliding, and scrambling through tho evergreen Malay jungle, wo finally reached “bukit lehah ” (literally the breathless hill), and found a small, empty Sakai camp. Like tho Semang villago at Serasa, it merely consisted of a few temporary and very crazy lean-to shelters, but in this case the floors were made of thin sticks plnced horizontally and | parallel, and raised about 6in. from the ground. They had just, been built by the women folk, whose exclusive duty it is | to erect them, and were only slightly raised from tho ground, so that they who watched by night could hear clearly and smell the approach of wild animals. Tho Sakni possess in I general great acuteness of the external senses, which in their cutting jtwo pieces of green bumboo, ouch about 2ft. in length and 6in. in diameter. A child manipulated them, and by striking the ends alternately against the root of a tree pro- duced an excellent imitation of the sound of a Malay native drum. The chief performers were three girls, who commenced shyly wjtli a scries of slow movements of their hands and bodies, and then, gradually gaining moro assurance, began to sing in a plaintive, monotonous chant, which grew quicker, until it bix-amo |a melody, to which they moved in and out and danced with unrestrained grace, as it to tho measure of a simple minuet. Even the habitually serious nnd ironical expression of tho tohj kuen softened nt the sight of this artless impromptu entertainment, at. the conclusion of which wo left, the camp. These ]>oor outcasts of civilisation and society hail danced for us in the heat of tho day, and I could not. help thinking, as wo returned gravely to tho civilisation of our headquarters, how fascinating their performance would have been if held on some chosen sward by tho silvery light of an Eastern moon, instead of on a roughly cleared space under the perpendicular rays of la tropical sun. John D. Gimlette.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b28103208_0159.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)