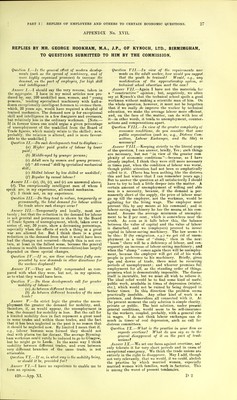

Report of the Royal Commission on the Poor Laws and Relief of Distress. Appendix Volume XI. Miscellaneous.

- Royal Commission on the Poor Laws and Relief of Distress 1905-09

- Date:

- 1911

Licence: In copyright

Credit: Report of the Royal Commission on the Poor Laws and Relief of Distress. Appendix Volume XI. Miscellaneous. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Library & Archives Service. The original may be consulted at London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Library & Archives Service.

35/228 (page 27)

![APPENDIX No. XVII. REPLIES BY MR. GEORGE HOOKHAM, M.A., J.P., OF KYNOCH, LTD., BIRMIMGHAM, TO QUESTIONS SUBMITTED TO HIM BY THE COMMISSION. Question I.—Is the general effect of modern develop- ments {such as the spread of machinery, and of more hicjhhj organised processes) to increase the demand, on the part of employers, for high skill and intelligence? Answer I.—I should say the very reverse, taken in the aggregate. I have in my mind articles now pro- duced by, say, 100 unskilled men, women, and young pereons, tending Bpecialised machinery with, half-a- dozen exceptionally intelligent foremen to oversee them, which, 20 yeans ago, would have required a shopful of trained meahanics. The demand now is for exceptional skill and intelligence in a few deeigners and overseers, but relatively less in the ordinary workmen. [Note.— If in former times one could argue a given percentage of unemployment of the unekilled from the Board of Trade figures, which mainly relate to the skilled ; now, probably, the relation is altered, and is more favour- able to the unskilled.] Question II.—Do such developments tend to displace:— (a) Higher paid grades of labour by lower paid ; (6) Middle-aged by younger persons; (c) Adult men by women and young persons; (d) All-round skill by specialised mechanical skill; (e) Skilled labour by less skilled or unskilled; (f) Begular by casual labour? Answer II.—(a), (b), (c), and (e) are answered above. (d). The exceptionally intelligent men of whom I speak are, in my experience, all-round mechanics. (f). I think not, in niy experience. Question III.-—Do they tend to reduce, temporarily or permanently, the total demand for labour within the trade where such changes occur? Answer III.—Temporarily and locally, most cer- tainly ; but that the reduction in the demsind for labour is not general and permanent is shown by the Board of Trade figures of unemployment, which, taken over a series of, say, 30 years, show a decreasing percentage, eispecially whem the effects of euch a thing as a gi'eat war are allowed for. But I think there is a great reduction in the demand from what it would have been had the changes not occurred—though this is not cer- tain, at least in the fullest sense, becauBe the general advance in wealth (demand for commodities) has largely depended on these spscial changes. Question IV.—If so, are these reductions fully com- pensated by new demands in other directions for the workers displaced? Answer IV.—They are fully conpensated as com- pared with what they were, but not, in my opinion, as to what they would have been. Question V.—Do these developments call for greater mobility of labour— (a) As between different trades; and (b) As between different branches of the same trade ? Anm'cr V.—^In strict logic the greater the unem- ployment the greater the demand for mobility, and, therefore, if, as would appear, the unemployment is leas, the demand for mobility lie less.. But the call for a limited mobility does in fact i-epresent a great need in some trades and within those trades, and the fact that it has betn neglected in the past is no reaeon that it should be neglected now. By limited I mean that if, e.g., labour bureaus were formed they siliould not deal with places too far distant. The average Birming- ham workman could rarely be induced to go to Glasgow, but he might go to Leede. In the isame way I think mobility between diffei-ent trades, and even between very different branches of the same trade, is not attainable. Qucition VI.—If so, in what way is the mobility being, or should it be, provided for? Answer VI.—I have no experience to enable me to form an opinion. Question VII.—In view of the requirements now made on the adult worker, how would you suggest ■ that the youth be trained? Would, e.g., any modification of the apprenticeship system, or technical school education meet the case? Answer VII.-—Again I have not the materials for a constructive opinion; but, negatively, we often say at Kynoch's that the technical school spoils a good workman without making a scientific man of him. On the whole question, however, it must not be forgotten that if we really do improve the worker by technical education, we make the average labour more efficient, and, on the face of the matter, can do with less of it—in other words, it tends tO' unemployment, counter- actions and compensations apart. Question VIII.—In view of the greater complexity of economic conditions, do you consider that some public organisation {such as, e.g., Distress Com- mittees, Labour Exchanges, and the like) is necessary ? Answer VIII.—Keeping strictly to the literal scape of the question, I can answer, briefly, Yes; such things are necessary, but not in view of the greater com plexity of economic conditions—^because, as I have already implied, I think they were still more necessary in times past, when the condition of labour was worse, though public attention had not been so emphatically called to it. (There has been nothing like the distress this and last winter that I can remember years ago.) But to answer the question at all satisfactorily I should have to' try to look a little deeper into the matter. A certain amount of unemployment of willing and able men is a necessity, because, if the demand is per- manently short of the supply, the price of labour must go up till the employer, not the w^orkman, would be agitating for the living wage. The employer must prevent this by any means at his command; and in labour-saving machinery he has the means at his com- mand. Assume the average minimum of unemploy- ment to be 2 per cent., which is somewhere near the truth. As soon as it falls below this, the balance between the value of capital and th© value of labour is disturbed, and we (employers) proceed to invest capital in labour-saving machinery. The law seems to be this: If (by emigration, e.g.) we get rid of unem- ployment in a time of slump, then in the next boom there will be a deficiency of labour, and con- sequently an increase of labour-saving machinery; and when the slump comes again there will be unemploy- ment, because the employer will get rid of his work- people in preference to his machinery. Briefly, given ups and downs of trade, there must be recui-ring periods of unemployment; and whoever promises full employment for all, as the standing order of things, promises what is demonstrably impossible. The disease itself is incurable, but we must all wish to relieve it. The ideal relief would be to find some kind of useful public work, available iu times of depression (winter, etc.), which would not be ruined by being dropped in better times. In this direction the problem seems practically insoluble. Any other kind of work is a pretence, and demoralises all connected with it. At the present moment the only solution is simple charity, private or public. The best solution, under present general conditions, woidd seem to be self-insurance by the workers, coupled, probably, with a general rise iu wages. I do not think labour exchanges can do much in times of real depression, such as call for distress committees. Question IX.—What is the practice in your firm a» regards overtime? What do you say as to the general disapproval of it on the part of trade unions? Answer IX.—We set our faces against overtime, and only tolerate it for very short periods and in cases of exceptional emergency. We think the trade unions are entirely in the right to disapprove. May I add, though not very relevantly, that we would, if we could, abolish the practice by which married women, especially married women with families, work in factories. This is among the worst of present tendencies.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b24399693_0035.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)