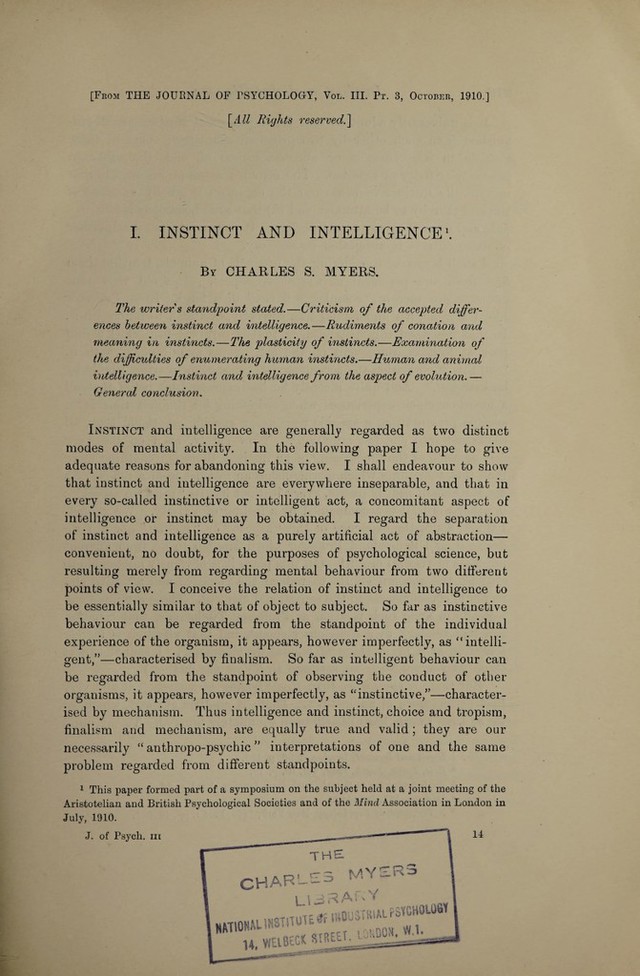

Instinct and intelligence / by Charles S. Myers. Instinct and intelligence : a reply / by Charles S. Myers.

- Charles Samuel Myers

- Date:

- [1910?]

Licence: In copyright

Credit: Instinct and intelligence / by Charles S. Myers. Instinct and intelligence : a reply / by Charles S. Myers. Source: Wellcome Collection.

6/20 page 212

![to reach its highest development, have been observed to learn by imitation from older ants1. Instincts are almost always modifiable and perfected by later experience. Indeed, a “ perfect reaction is apt not to need subsequent modification. It can adequately be worked by mechanism. Consciousness, especially those elements of conation and meaning which we have just been considering, will become unnecessary, nay, must even prove disadvantageous. A reflex is the nearest example of such a condition. (But even a reflex proves to be not ‘ absolutely ” fixed, and may prove to be not “ absolutely ” unconscious. All that can be said is that its central consciousness, if present, is always a terra incognita, never communicable to the Ego of the organism.) From the point of view of definition, it would be bettei to call the flight of moths towards a lamp a reflex, not an instinct , no amount of experience alters the reaction. Nor do different individuals of the same species or the same individuals on different occasions show that uniformity of action, which has been often regarded as characteristic of instincts. Take, for in¬ stance, the following observations by Mr and Mrs Peckham on the habits of solitary wasps, which, with some of his remarks, I quote from Professor Hobhouse2. “ ‘ When the provisioning is completed the time arrives for the final closing of the nest, and in this, as in all the processes of Ammo- phila, the character of the work differs with the individual. For example, of two wasps that we saw close their nests on the same day, one wedged two or three pellets into the top of the hole, kicked in a little dust and then smoothed the surface over, finishing it all within five minutes. This one seemed possessed by a spirit of hurry and bustle, and did not believe in spending time on non-essentials. The other, on the contrary, was an artist, an idealist. She worked for an hour, first filling the neck of the burrow with fine earth which was jammed down with much energy, this part of the work being accom¬ panied by a loud and cheerful humming, and next arranging the surface of the ground with scrupulous care and sweeping every particle of dust to a distance. Even then she was not satisfied, but went scampering around hunting for some fitting object to crown the whole. First she tried to drag a withered leaf to the spot, but the long stem 1 E. Wasmann, Comparative Studies in the Psycholog]) of Ants and of Higher Animals (Eng. trans.). St Louis, 1905, p. 68. Cf. also Lloyd Morgan, op. cit. p. 131. 2 Mind in Evolution, London, 1901, pp. 68, 70. Cf. also G. W. and E. G. Peckham, Wasps Social and Solitary, Boston, 1905.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b30615446_0006.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)