Medical women : a thesis and a history / by Sophia Jex-Blake.

- Sophia Jex-Blake

- Date:

- 1886

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Medical women : a thesis and a history / by Sophia Jex-Blake. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by The Royal College of Surgeons of England. The original may be consulted at The Royal College of Surgeons of England.

335/366 (page 71)

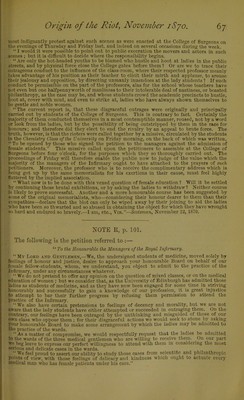

![twice over on a certain point,—‘ I do not say that it was so ; I say tliat I was toid so.' It was mainly due to this legal technicality that, with great reiuctance, I acquiesced in the desire of my lawyers that I should not maintain the issue of ‘ Veritas,’ as had been my strong wish and intention ; nor should I have yielded even then had I not been positively assured by them that the absence of this plea would in no way interfere with my bringing all the facts to liglit, and proving to the public exactly what grounds I had for my statements. You know that the judge ruled otherwise at the trial, and it is of course impossible for me to say whether he, on the one hand, or my counsel, including the Lord Advocate, on the other, were legally correct. It is useless for me now to regret that I allowed myself to be overruled on tills matter by the statement made to me of the legal technicalities, and I think that the event of this day shows that I have in truth no need to regret the course of events. I believe that no one left the Court, and I trust no one will leave this room, without a firm conviction that my one desire was for a full and thorough investigation of all the facts of the case; and 1 leave it for you to decide how far the same desire was manifested by the pursuer, who would not even enter the witness-box until compelled by my counsel to do so. —Scotsman, Oct. 10,1871. The following letter, written, I understand, by a lawyer, is worth quoting from the Aberdeen Journal:— “Sir,—No one can read the proceedings in the case Craig v. Jex-Blake—in the Court of Session, before Lord Mure and a Jury (1st June 1871)—without being struck with the anomalous state of the law of libel. The pursuer comes into Court, alleging that his character has been slandered and defamed. That, of course, implies that he is free from blame in regard to the matters about which the slanderous words were spoken. The defender, on the other hand, denies the libel—that is, in general terms, that the words uttered are not slanderous, or that she was justified in using them, as they were pertinent to the subject under discussion when she used them, and so were not slanderous. But she does not choose to say so, upon the record—that is, in other w ords, she does not choose to reiterate the slander, if it is slander, or, if it is not, to be guilty of what is really slander, because untrue and unjustifiable; and for this forbearance on her part, for this delicacy of sentiment and conduct, she is, forsooth, prevented from proving what the jiursuer said or did, under certain circum- stances which would fully justify the expression used. Is this state of things consistent with law and justice? I should say not. When a person comes into Court complaining of lieing slandered and abused, it is understood that he comes into Court with clean hand.s. When a man in such circumstances complains to the public, and conies into Court for redre.ss, he puts his character into the scales, and it ought to be fairly weighed. He ought not to be allowed to shelter himself under a technical objection, when all the time he knows in his heart and conscience that he is complaining of liis actual doings as slanderous—when he knows they are true, and that they are no slander. “ We have a good rule in our Scotch criminal law, applicable to subjects such as these. A man is accused of murder, and he pleads ‘not guilty.’ When the trial conies on, he is not prohibited from asking questions to prove that he is not guilty of murder, hut that what he did was in self-defence, and that he had not only OTeat provocation, but that flic deceased struck the first blow, and put his (the defender’s) life in imminent danger. On the contrary, the judges in all criminal cases pronounce a special interlocutor of what is called relevancy, allowing the panel (so the accused is named) to prove all relevant facts and ciremn- stances tending to elide (that is to set aside) the libel. And why should it not be so in cases of libel for defamation of cliaractcr? The cases are quite parallel—one for killing a man, tlie other for killing a man’s reputation—in many cases more dear to him than his life. “ This state of the law is quite deplorable. The learned judge who tried the case of Craig v. Jex-Blake quite appreciated tlie incongruity when he observed to the jury that, under the issue as frameil, it was his duty to tell them that they must assume, as the ]iursuer’s counsel con- tended, that the expressions used were false, because the defendant had not undertaken to prove that they were true, that is, that it was the duty of a man not only to dclend expres- sions used in the heat of debate, or in support of an object of importance in wliich he was interested, but also that he must go out of his way to reiterate the caliiiiiny, it it ‘‘ calumny. This is like school boys and girls saying to one another—‘ 1 said it, and I will l»rovc it too.’ It is no wonder though his Lordshiji added ‘ that it niiglit seem odd to the jury that such a rule should exist; ’ and the only apology his Lordshiii could make lor it was that it was a rule laid down by judges of great eminence, and had been acted upon in this country for a long series of years.’ Nothing could be more preposterous or absurd. Another grounil of defence, which seems to be excluded if the defendant does not put niton record the veritus eonvicii—the truth of the alleged slander, is that of ‘privilege.’ Thus, where a man acts along with others in a conjoint concern, and a dispute occurs about the execution of it, it woiilti seem quite jiistifialile to maintain that words spoken, though seeming to attect the character of the isirties, or any of them, should be called ‘ privileged ’—that is, not subject to prosecu-](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b22305890_0335.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)