Report on the outbreak of plague at Sydney [1900-1907] / by J. Ashburton Thompson, Chief Medical Officer of the Government and President of the Board of Health.

- New South Wales. Department of Public Health

- Date:

- 1900-1908

Licence: In copyright

Credit: Report on the outbreak of plague at Sydney [1900-1907] / by J. Ashburton Thompson, Chief Medical Officer of the Government and President of the Board of Health. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Library & Archives Service. The original may be consulted at London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Library & Archives Service.

247/452

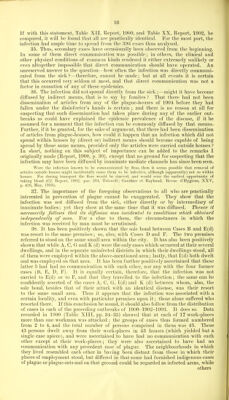

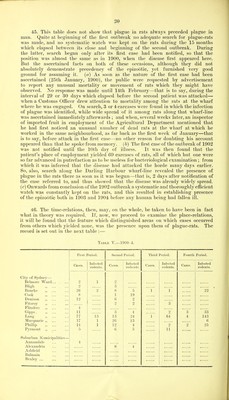

![soon as the circumstances are examined. Thus:—B was a labourer regularly employed at a collection of bonded stores to which a wharf was attached, at both of which plague-rats were found ; while E, a carman in other employment, was not attacked until 15 days after B, nor until 12 days after B had been isolated. It is not possible that E should bave received infection from B. But he had been exposed to the same circumstances as B; for he had worked at the wharf during the whole of the third day before liis attack, and the last observed plague-rat at that wharf had been gathered by the intelligence staff the day after he had worked there. So also, although the cases of D and E were connected with the same mill premises, the two men had never met. D was employed at the mill, Avhile E was merely a member of the cleansing gang which entered it 6 days after D had been seized and had gone to his distant home, 5 days after he had been isolated. Communication of the infection from D to E was impossible; and again, there was liere merely exposure to the same circumstances, for E was engaged with others in collecting the dead and plague rats which were found at D's place of employment. Between M(d) and L(d) there had been close communication during some part of the tirst 36 hours of L.'s illness. L, who was a coachman, inhabited stables attached to a large mansion ; M, was the housekeeper, and lived in the house, whence she went across to the stables after L had fallen ill, to see to his wants, and she sat up with liim at night during the second 24 hours of his illness. The house was not infested by rats, and it was inhabited by other people none of whom suffered. At the stables, L was known to have picked up two dead rats, and to have killed a sick rat in his bedroom alcove them shortly before attack; and after notification of his case, Mobile putrid carcases were found among dunnage in the loft on which his bedroom opened, and close to its door, plague was identified in 2 rats trapped at the stables at the same time. M Avas exposed, therefore, not merely to L, but also to the very circumstances in which he had received his infection from some source which quite certainly was not a precedent case in man ; and therefore, although the possibility of direct communication cannot be excluded, I am unable to regard it as the most probable explanation of M's case. Thus but a shadow of doubt whether in one couplet out of three the infection may not have been directly communicated from the primary case, falls on the series of 12 cases now under reviews I take the opportunity of saying distinctly, however, that I am far from denying the occasional occurrence of direct communication which, indeed, not merely must be possible but has been actually observed by others in specific instances; and of pointing out that my chief concern at this time is not with the occasional causes of individual cases, but with the general, constant, causes of epidemic prevalences of bubonic and of septicaemic plague. 33. How^ does this jiart of the teaching drawn from the short series of 1904 stand comparison with the wider experience of 1900 and 1902 ? In the former year, 10 households out of 276, and in tlie latter, 9 out of 124 yielded multiple cases ; and while in both years some of the secondaries might possibly have received the infection from their primaries, others of them in both yeai-s could not have done so. The evidence that this was so cannot be summarised, except at cost of depriving it of all its cogency ; refer(>nce must be made, therefore, to the original records (Reports, 1900, pp. 34-6; 1902, pars. 196-207) where the circumstances of the two series referred to were described. Nevertheless, attention may be specially directed here to that important group of 7 cases (Report, 1902, pars. 199-202) which actually furnished examples of both the contingencies under discussion, in that while some of its conij)onent persons could have received the infection direct, 2 of them could not have done so, fo]' the sufficient reason that they had left the premises before the first of the remaining 5 had fallen ill. On the 2nd and 3rd days after having left they were themselves attacked, on j)remises to wliich no suspicion of infection then or afterwards attached. It appears, then, that experience on this point also has been U7iiform and consistent. 34. But were the otlier members of the households to which these 12 patients belonged exposed to them sufficiently long after the beginning of their illness for direct communication to have taken place ? The time during which such exposure continued was as follows in each case :—E(d), 17 hours ; A, 30 ; G, 36 ; 1(d), 51; L(d), 51 (at home till death); M(d), 52 (at home till death); K(d), (50 ; C, 63 ; B, 72 ; E, 96; D, 99 (part in a general ward) ; and 11(d), 144 hours (in a general ward till death). If](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21354704_0247.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)