Report on the outbreak of plague at Sydney [1900-1907] / by J. Ashburton Thompson, Chief Medical Officer of the Government and President of the Board of Health.

- New South Wales. Department of Public Health

- Date:

- 1900-1908

Licence: In copyright

Credit: Report on the outbreak of plague at Sydney [1900-1907] / by J. Ashburton Thompson, Chief Medical Officer of the Government and President of the Board of Health. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Library & Archives Service. The original may be consulted at London School of Hygiene & Tropical Medicine Library & Archives Service.

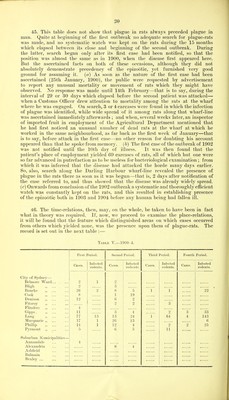

249/452

![others had not done so. Now, in the first place, there were 2 groups, wliich comprised 3 and 2 persons respectively, of which all the members lived in ditferent, uninfected, neighbourhoods; the sole bond between them was resort to the 2 places at which they worked, and Avhich stood on an infected area. Secondly, there were 10 work- places at which 28 persons were attacked in groups of from 2 to 4 persons at each; 14 of them did, while the other 14 did not, reside in infected neighbourhoods, and each of the 10 groups included representatives of both kinds of neighbourhood. As to the 14 who lived in uninfected neighbourhoods, there was no other bond between them and the remaining 14 than resort to the same work-places; as far as they were concerned there seemed to be no room for doubt that they were infected at their places of employment and nowhere else. That being so, no reason appeared for j^referring the supposition that the other 14 had become infected in some untraceable way in the infected neighljourhood in which they dwelt, rather than at the work-places which had certainly been the source of infection ibr the 14 first-mentioned. Lastly, 5 AVork-places furnished groups of 2 each, of which groups both members resided in infected neighbourhoods; from them, taken by themselves, nothing to the present purpose could be inferred. They Avere included in the table because it was intended to exhibit frankly all known facts of the class under examination; I now maintain them there partly because the evidence afforded by the 12 groups already analysed was so nearly demonstrative; partly, also, because the expression infected neighbourhood was intended to, and did, represent a mere chance which was mentioned as a precaution against omission of a circumstance of possible importance, rather than any probability of efficient infectivity towards the persons now referred to. It will appear presently, indeed, that a neighbourhood or area is not infective in general, l)ut only in virtue of particular buildings which are infected and which stand upon it. Similar observations were recorded in 1902 (lleport, 1902. par. 209, Table XXIII), though in smaller number, as w^ell as in 1903; they had more apparent (not real) weight from the greater fulness with which the details were described. Thus the data recorded in 1900, 1902, and 1903 resembled those now recorded of 1904, and the third conclusion drawn from the experience of 1900 (Eeport, p. 41) is now seen to have been fully corroborated by the results of further observation during those later outbreaks. This was that the infection Avas associated with localities. 39. What was the nature of the association between the infection and localities in which it had been shown to exist by attack of persons who had resorted to them, but who were ascertained to have been dissociated from each other under every other aspect ? The infection is living; it must l^e present, therefore, in or upon something which not merely permits it to survive, but enables it to flourish, for it must other- wise be confined to the spot whereon it was first deposited, which, of course, does not happen. Qnd localisation, its possil)le niduses a))pear to be comprised under the three headings, air, water, and soil. In the air it could not continue and, above all, could not flourish any more than other infections of like nature. By Avater it Avas not conveyed at Sydney (E.eport, 19U0, p. 30; the reasons there given apply equally to the outbreaks of 1902 and 190 i), and it is noAV generally agreed that by Avater it cannot be conveyed {Conference Sanilaire de Paris, 1903, Proces-verhaux, p. 88; exceedingly cautious though this Conference Avas in expressing itself on most points, it adopted the opinion Veau potable ne joue <nieun role dans la propagation de la, peste Avithout discussion). In the earth it miii'ht live, continue, and in some sense flourish, as sonit^ members of the group of organisms AAdiich cause hiemorrhagic septicEemia (to Avhich h. pestis has hitherto been generally ccmsidered to belong— the pasteurelloses) appear to do. But this has not been established for the particular micro-organism noAV under notice, and, w ithout denying that it might find a place in the surface soil of cities, it must be admitted that there it Avould be exposed to a thousand inimical accidents. A])art from that consideration, did it groAV in the soil it Avould probably persist in it. But the association betAA'een place and the infection at Sydney was not persistent. The uniform experience of 4 outbreaks has been that the most ordinary processes of scavenging and cleansing sufficed to banish it at once and for all.* On the whole, the observed phenomena indicate that the suggestion of association between the infection and the soil in relation to attack of man is unpractical (Cf. Reports, 1900, p. 40, or 1902, par. 203). 40. From Table V. (pp. 20, 21) it appears that some areas have become infected more than once. It is pointed ou t that the names which indicate them are tliose of extensive municipalities, and that the reinfection did not occur in th e neighbourhoods previously attacked. -19—C](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21354704_0249.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)