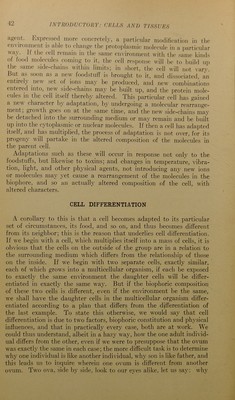

A text-book of pathology for students of medicine / by J. George Adami and John McCrae.

- John George Adami

- Date:

- 1914

Licence: In copyright

Credit: A text-book of pathology for students of medicine / by J. George Adami and John McCrae. Source: Wellcome Collection.

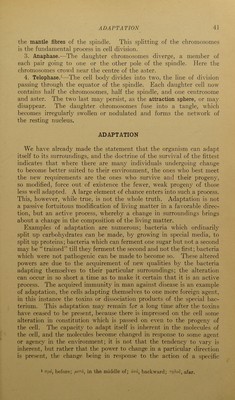

41/904 page 43

![CELL DIFFERENTIATION 4‘S is one going to become an elephant and one an insect, and how comes it that the elephant is certain to have a trunk and the insect wings? Is there, in the ovum, a ])art of the protoplasm that is definitely of such composition that it must form a trunk and not a tail? And where is the protoplasm hidden in one cell which will determine that this particular elephant will have tusks like his grandfather, a trunk like that of his great-grandfather, and the temper of his great-grandmother? Does the ovum contain a vast accumulation of molecules of different orders and properties which have directly descended from each of his thousand ancestors? This cannot be: we can prove, from what we know of the protein molecule, that there is actually not room for them. The theory of “the continuity of the germ plasm,” as it is called, which presupposes the descent from generation to generation of an infinitesimal part of the protoplasm of each, is a 'physical impossibility. Such “determinants” carrying particular properties derived from one or other ancestor, which shall in due time be distributed to one or other tissue or area of the fully grown individual and shall endow that particular tissue or area with the properties seen in one or other ancestor demands, it will be seen, that every separate feature in the body, even down to the particular markings of the thumb prints (which are alike in no two individuals), shall be present in the fertilized ovum, demands, in short, that not merely the microscopic nucleus of that ovum, but the chromatin or whatever part of it conveys the hereditary characters, shall be made up of these innumerable determi- nants. Now, according to Weismann, these determinants cannot be simple molecules of matter, but must be molecular groups, and as we have pointed out that living matter is proteidogenous, each individual molecule must be of a size which, according to physicists, is almost visible by the ultra-microscope.^ Regarded thus, it is a physical impos- sibility that the minute nucleus of the impregnated ovum can contain all the determinants demanded by this theory. If, therefore, we can- not accept the idea of determinants, is there any other means by which we can visualize the facts of inheritance and of individual variation? This biophoric hypothesis appears to us to afford the only means of explanation at present possible. The elephant ovum develops into an elephant and not into an insect because the elephant ovum is made up, in the main, of molecules of a certain average composition, a ring made up, let us say, of smaller rings each represented by A: a- A / \ A A \ / A—A—a A / \ A A \ / a—A—A That is, ill llie npighhorliood of 0.1/i in dianioter.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b28055172_0041.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)