Elements of agricultural chemistry, in a course of lectures of the Board of Agriculture / By Sir Humphry Davy.

- Humphry Davy

- Date:

- 1846

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Elements of agricultural chemistry, in a course of lectures of the Board of Agriculture / By Sir Humphry Davy. Source: Wellcome Collection.

124/318 (page 108)

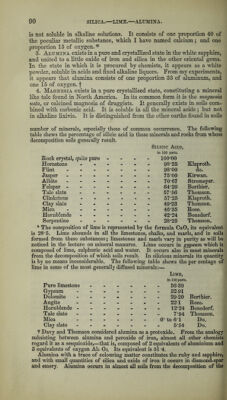

![REPLACEMENT OF ALKALINE BASES. This property has been very little attended to in a philosophical point of view; yet it is of the highest importance in agriculture. In general, soils that consist principally of a stiff white clay are difficultly heated; and being usually very moist, they retain their heat only for a short time. Chalks are similar in one respect, that they are difficultly heated; but being drier they retain their heat longer, less being consumed in causing the evaporation of their moisture. * portions, and the oxygen due to the portion that had in the wood been combined with organic acids was 11*47. Now the difference between the oxygen of the two is only T5, a still closer coincidence than in the former case. Should these remarkable results be confirmed, it follows that alkaline matter in definite quantity, is absolutely necessary; that one base can substitute or take the place of another; that where alkaline constituents, in insufficient quantity, are present in a soil, no manures, in which these are awanting, however rich in other constituents, can be beneficial, on the contrary, they must make matters worse, by facilitating the exhaustion of alkaline bases; and that the geological history of soils, and the determination of the minerals by whose decomposition they are produced, is a matter of far greater importance than was believed prior to the publication of Liebig’s views. It ought to be admitted that the plants cultivated in our fields are not in their natural state, and that further investigation is necessary before it is concluded that they are regulated by exactly the same laws as wild plants; still the doc- trine would so satisfactorily explain many anomalies familiar to practical agri- culturists, that it is difficult to resist the assumption. Certainly, no investigation is more worthy of the attention of competent chemists. From the remarks already made regarding the qualities of peas and potatoes, cultivated according to different methods, it would appear that an examination of the inorganic constitu- ents of these crops would be likely to throw much light on the subject. The doctrine of substitution is illustrated and strengthened by several facts previously well known, but never explained on any philosophical principle, till Liebig brought forward the doctrine and applied it to them. [Chemistry applied to Agriculture, 2d edition, page 98, et seq.] Thus the organic alkali Solanin which gives the poisonous property to potatoes grown without soil, would appear to be formed for the purpose of replacing the potash required by the healthy plant. Littoral plants, containing soda, can be grown, for a certain time at least, in soils affording only potash, and that base is found in their ashes. In opium, (the inspissated juice of the poppy,) the organic acid is generally a peculiar one, called mechonic; but sometimes this acid is awanting, its place having been taken by sulphuric acid. Several organic bases are found in opium, the most important are morphia and narcotina. The proportions of these vary, but an increase of the one always corresponds to a diminution of the other. Lastly, in cinchona bark, the organic acid is uniformly the kinic, while the bases are quina, cinchonia, and lime. Now it is found that all the three bases vary much in proportion, but manufacturers of quina know that unprofitable barks have the lime in excess, and profitable ones the organic alkalies. A little consideration of this doctrine will suffice to convince any one of its importance in directing a number of points connected with ordinary culture, to say nothing of that vast, though almost untouched field—the cultivation of plants for pharmaceutic purposes. * Chalks form remarkably dry soils on account of the porous nature of the rock. De la Beche well remarks to have seen “parts of a table-land, formed of a fair though gravely soil, resting on a tenaceous clay, drained naturally by means of pinnacles of chalk, which pierced through the clay in several places and entered the gravelly soil above. The portions of the soil above and near the chalk pinnacles being kept fairly drained by the well known property of the chalk readily to absorb moisture, while the portions of the soil which were too far from the draining influence of the pinnacles, were wet and heavy.”](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b2931236x_0124.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)