Fallacies of the faculty, with the principles of the chrono-thermal system of medicine : in a series of lectures originally delivered in 1840, at the Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly / by S. Dickson.

- Samuel Dickson

- Date:

- 1843

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Fallacies of the faculty, with the principles of the chrono-thermal system of medicine : in a series of lectures originally delivered in 1840, at the Egyptian Hall, Piccadilly / by S. Dickson. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by Royal College of Physicians, London. The original may be consulted at Royal College of Physicians, London.

193/204 (page 183)

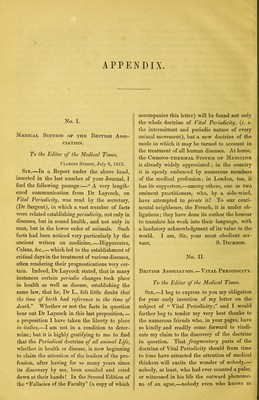

![ration. This method had been observed by the physicians (!) in her grace’s youthful days, and this she was resolved to abide by, as the most proper in this conjuncture, being fearful that her grandson might otherwise catch cold, and, by means of it, lose a life that was so precious to her and the whole nation. She had also taken a resolution to give her attendance upon the duke in person during his sickness, and was in the most violent consternation when RadclifFe at his first visit ordered the curtains of the bed to be drawn open, and the light to be let in, as usual, into his bed-room. ‘ How,’ said the duchess, ‘ have you a mind to kill my grandson?—Is this the tenderness and affection you have always expressed for his person—’tis most certain his grandfather and I were used after another manner, nor shall he be treated otherwise than we were, since we recovered [escaped, truly!] and lived to a great age without any such dangerous experiments’ ‘All this may be,’ replied the doctor, with his wont- ed plainness and sincerity, ‘ but I must be free with your grace, and tell you, that unless you will give me your word that you’ll in- stantly go home to Chelsea and leave the duke wholly to my care, I shall not stir one foot for him; which, if you will do, without inter- meddling with your unnecessary advice, my life for his, that he never miscarries, but will be at liberty to pay you a visit in a month’s time.’ When at last, with abundance of diffi- culty, that great lady was persuaded to acqui- esce and give way to the entreaties of the duke and other noble relations, and had the satisfac- tion to see her grandson, in the time limited, restored to perfect health, she had such an implicit belief of the doctor’s skill afterwards, that though she was in the eighty-fifth year of her age at that very time, she declared it was her opinion that she should never die while he lived, it being in his power to give length to her days by his never-failing medicines.” Well, Gentlemen, the proper medical treat- ment of all diseases comes, at last, to attention to temperature, and to nothing more. What is the proper practice in Intermittent Fever? To apply warmth, or administer cordials in the co/d!stage; in the hot to reduce the amount of temperature, by cold affusion and fresh air; or, for the same purpose, to exhibit, according to circumstances, an emetic, a purgative, or both in combination. With quinine, arsenic, opium, &c., the interval of comparative health—the period of medium temperature, may be pro- longed to an indefinite period, and in that manner may health become established in all diseases—whether, from some special local de- velopment, the disorder be denominated mania, epilepsy, croup, cynanche, the gout, the influ- enza I In the early stages of disease, to arrest the fever is, in most instances, sufficient for the reduction of every kind of local development. A few rare cases excepted, it is only when the disorder has been of long standing and habi- tual, that the physician will be compelled to call to his aid the various local measures, which have a relation to the greater or less amount of the temperature of particular parts. The Unity of Disease was first promulgated by Hippocrates, and for centuries it was the ancient belief. In modern times it found an advocate in the American physician Rush— but except in this instance of unity, betwixt the respective doctrines of both authors and my doctrine of disease there is not a single feature in common. For while the first, from his observation of the resemblance of disorders one to another, inferred that one imaginary humour must be the cause of all complaints— the doctrine of the second was that all disorders consisted in one kind of excitement. The prin- ciple of Hippocrates led him to purge and sweat;—that of Rush to bleed, leech, and starve. In practice and in theory I am equal- ly opposed to both. Other physicians doubt- less have held the idea of a unity of disease, but neither in the true theory of the nature of morbid action, nor in the principle of the practical application of medical resources have I as yet found the chromo-thermal system anticipated. The opponents of my doctrines, and those who embrace them by stealth, have alike searched the writings of the ancients in vain to discover a similarity to them in either respect. If it be urged against the author of the chrono-thermal system of medicine, that he has availed himself of facts collected by others—and that therefore all is not his which his system contains—I answer. Facts when disjointed are the mere bricks or materials with which the builders of all systems must](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b28037789_0195.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)