Facial spasm and tic, torticollis : diagnosis and treatment / by Tom A. Williams.

- Williams, Tom A. (Tom Alfred), 1870-

- Date:

- 1910

Licence: In copyright

Credit: Facial spasm and tic, torticollis : diagnosis and treatment / by Tom A. Williams. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by The Royal College of Surgeons of England. The original may be consulted at The Royal College of Surgeons of England.

3/8 (page 3)

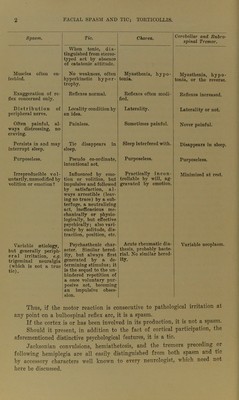

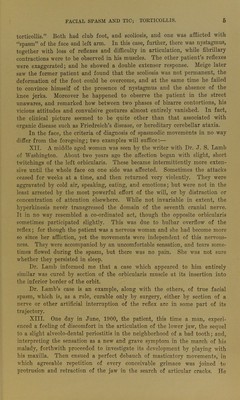

![This Ka.Kor]6r]<; which invariably precedes the explosion of the true tic, ranges it among physiological acts, all of which when postponed beyond their due period will cause intense desire for their performance, which is followed by relief, just as is the tic. It is, however, a physiological act perverted; for it is ill-timed, being dependent upon no adequate stimulus, being unnecessary to the body’s health or ultimate comfort, and being beyond the power of inhibition by the patient’s enfeebled will, which evidences itself, as a rule, by other stigmata of the psychasthenic state. Into these I cannot enter here, save to mention the scrupulosities, timidities, feelings of inade- quacy, desire for peculiarity, as well as the want of correspondence of the emotions with the real situation, showing itself by intense joy or sadness over trifles, the morbid fears, and the painful anguish, sometimes indeed a prropos of nothing which such patients exhibit. The arousing of this last symptom when the patient tries to suppress the tic is pathognomonic, distinguishing it from a true spasm. The psychic symptoms of these patients are described with much insight and fulness and clarity by Janet3. The following cases illustrate these points:— I. Occipital neuralgia and pain in the neck led the patient to try various positions to allay the agony, in the course of which he found that rotation to the right brought transient relief. By dint of repetition, the movement became involuntary (Brissaud and Meige). II. In this case, the subject used to spend the whole evening inert, arms folded, without reading or working, tilting his head forward or backward to re-discover a “cracking?” in his neck from which he suffered—a proceeding which gradually developed into a tic (Brissaud and Meige). III. In another case, a school girl was dissatisfied with the place allotted to her in the schoolroom, and pretended that she felt a draught on her neck coming from a window on her left. The initial movement was an elevation of the shoulder as if to bring her clothes a little more closely round her neck; then she commenced to depress her head and indicate her discomfort by facial grimaces; and these eventually passed beyond voluntary control (Raymond and Janet). The three cases just cited illustrate the causation of tic by definite peripheral stimulus. IV. A case arising from a habit attitude was that of a woman who used to pass the day sewing or knitting at her window and amusing herself from time to time by pensively looking out into the street. Not long afterward, she noticed how much more pleasant it was to allow her head to turn to the right, and how troublesome it was to keep it straight. At length she found this impossible, except with the aid of her hands (Sgobbo4). V. Another case of habit movement is that of the tic of the colporteur i.e., the heaving of the shoulders due to the habit of carrying heavy weights upon them5. VI. The peripheral source of tic is well illustrated by the case Lannois5 caused by the constant looking at a papilloma on the nose and cured by the removal of the growth.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b2242586x_0005.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)