Auricular fibrillation and its relationship to clinical irregularity of the heart / by Thomas Lewis.

- Thomas Lewis

- Date:

- [1910?]

Licence: In copyright

Credit: Auricular fibrillation and its relationship to clinical irregularity of the heart / by Thomas Lewis. Source: Wellcome Collection.

22/80 (page 324)

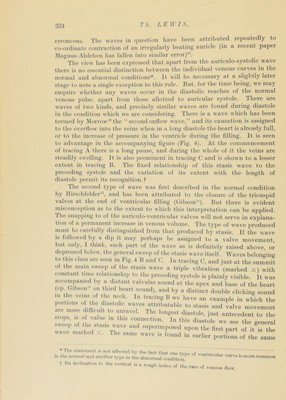

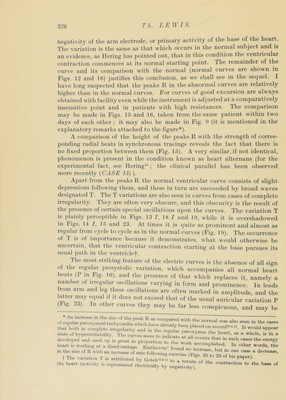

![Th. ].E]Y1S. erroneous. The waves in question have been attributed repeatedly to co-ordinate contraction of an irregularly beating auricle (in a recent papci. IMagnus-Alsleben has fallen into similar error)^. The view has been expressed that apart from the auriculo-systolic wave there is no essential distinction between the individual venous curves in the normal and abnormal conditions*. It v ill be necessary at a slightly later stage to note a single exception to this rule. But, for the time being, we may enquire whether any waves occur in the diastolic reaches of the normal venous ])ulse, apart from those allotted to auricular systole. There are waves of two kinds, and precisely similar waves are found during diastole in the condition which we are considering. There is a wave which has been termed by Morrow'® the “second onflow wave,” and its causation is assigned to the overflow into the veins when in a long diastole the heart is already full, or to the increase of pressure in the ventricle during the filling. It is seen to advantage in the accompanying figure (Fig. 4). At the commencement of tracing A there is a long pause, and during the whole of it the veins are steadily swelling. It is also prominent in tracing C and is shown to a lesser extent in tracing B. The fixed relationship of this stasis wave to the preceding systole and the variation of its extent with the length of diastole permit its recognition.! The second type of wave was first described in the normal condition by Hirschfelder^, and has been attributed to the closure of the tricuspid valves at the end of ventricular filling (Gibson'). But there is evident misconception as to the extent to which this interjDretation can be apiDlied. riie snapping to of the auriculo-ventricular valves will not serve in explana- tion of a permanent inciease in venous volume. The type of wave produced must be carefully distinguished from that produced by stasis. If the vrave is followed by a dip it may perhaps be assigned to a valve movement, but only, I think, such part of the wave as is definitely raised above, or depressed below, the general sweep of the stasis wave itself. Waves belonging to tins class are seen in Fig. i B and 0. In tracing C, and just at the summit 01 the main sweep of the stasis wave a triple vibration {marked x) with constant time relationship to the preceding systole is plainly visible. It was accompanied by a. distant valvular sound at the ape.x and base of the heart (cp Gibson' on third heart sound), and by a distinct double clicking sound in the veins ot the neck. In tracing B we have an example in which the portions o die diastolic waves attributable to stasis and valve movement are more difficult to unravel. The longest diastole, just antecedent to the stops, IS of va.iie in this connection. In this diastole we see the general rrc^“i u l e7x '‘'T^^^ fir^tpart of it is the wave nuuked x. Ilie same wave is found in earlier portions of the same * I lio stateinoivt is not affected liv tlio fnnf tlini- + r . in tlio normal and anotlior typo in the abnormal conditioJi^'^ '’entncular curve is more common t Its inclination to the vortical is a rough index of the rate of venous flow.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b29000610_0022.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)