Prehistoric man and his early efforts to combat disease / by T. Wilson Parry.

- Parry, Thomas Wilson, 1866-1945.

- Date:

- 1914

Licence: In copyright

Credit: Prehistoric man and his early efforts to combat disease / by T. Wilson Parry. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by The Royal College of Surgeons of England. The original may be consulted at The Royal College of Surgeons of England.

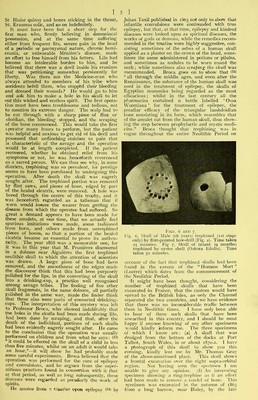

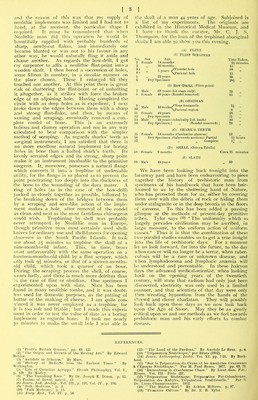

10/12 (page 8)

![iind the reason of this was that my supply of neolithic implements was limited and I had not to hand, at the moment, the particular shape I tequired. It must be remembered that when Neolithic man did this operation he would be bountilfully supplied with probably hundreds of sharp, newly-cut flakes, and immediately one became blunted or was not to his favour in any other way, he would naturally fling it aside and choose another. As regards the bow-drill, I got my carpenter to affix a neolithic flint-point into a wooden shaft. I then bored a succession of holes, some fifteen in numbei', in a circular manner on the place chosen. These I enlarged till they touched one another. At this point there is great risk of shattering the flint-point or of unhafting it altogether, as it strilces with force the broken edge of an adjoining hole. Having completed the circle with as deep holes as is expedient, I next broke down the edges between them with a sharp and strong flint-flake, and then, by means of sawing and scraping, eventually removed a com- plete rondel of bone. This is an extremely tedious and clumsy operation and not in any way calculated to bear comparison with the simpler method of scraping. As regards sharks’ teeth as surgical instruments, I am satisfied that there is no more excellent natural 'implement for boring holes in bone than a halted shark’s tooth. Its keenly serrated edges and its strong, sharp point make it an instrument invaluable to the primitive surgeon. It, moreover, possesses a natural flange which converts it into a trephine of undeniable utility, for the flange is so placed as to prevent the point penetrating too deeply into the thickness of the bone to the wounding of the dura mater. A ring of holes (as in the case of the bow-drill) packed as closely together as possible, followed by t'le breaking down of the bridges between them by a scraping and saw-like action of th'C imple- ment makes a hole, after removal of the rondel as clean and neat as the most fastidious chirurgeon could wish. Trephining by shell was probably never attempted 'by Neolithic man in Europe, though primitive man most certainly used shell- knives for ordinary use and shell-lancets for opening absce'sses in the South Pacific Islands. It took me about 25 minutes to trephine the skull of a nine-months-old infant. This, in time, bears most unfavourably with the same operation on a fourteen-months-old child by a flint scraper, which only took gj minutes, or that of a sixteen-months- old child, which took a quarter of an hour. During the scraping process the shell, of course, wears badly, and there is much more detritus than in the case of flint or obsidian. One specimen I experimented upon with slate. Slate has been found in many neolithic tombs, and it was doubt- less used for domestic purposes, as the patting of butter or the making of cheese. I am quite con- vinced it was never employed as a trephine, for it is too soft and friable; but I made this experi- ment in order to test the value of slate as a boring implement as regards bone. It took me O'Carfy 50 minutes to make the small hole I was able in tlie skull of a man 44 years of age. Subjoined is a list of my experiments. The ■ originals are exhibited in the Historical Medical Museum, and 1 have to thank the curator, Mr. C. J. S. Thompson, for the loan of the trephined aboriginal skulls I am able to show you tliiis evening. (A) FLINT No. Sex (1) Flint Scrapers Age. 1 Female 14 months 2 16 months 4 ) /Frontal hole ’* 5 years / \Parietal hole 91 10 I u 12 13 14 ,, 21 years Dry Specimen (2) Bow-Drill (Flint-point) 7 Male 68 j'ears (1st stage only) 8 Female 40 years (Rondel removed) Male lOweeks. \F (B) OBSIDIAN 'Near fontanelle .Parietal region Female 44 years Dry Specimen Male 44 years (Admiralty Isd, knife) Dry Specimen [ ,, (Rondel removed) ] Time Taken. 9i minutes 15' „ 18 15 30 2Si „ 25 65 14 8 28 31 30 78 (C) SHARK’S TEETH 15 Female 14 months (Carcharias glaucus) 12 „ 16 Dry Specimen (Galeocerdo arcticus) Partial IJ hours 17 ,, ,, Complete 1;J ,, (D) SHELL (Ostreea Edulis) 18 Female 9 months Circa 25 minutes 19 Male 44 years (E) SLATE 50 VVe have 'been looking back to-night into the far-away past and have been endeavouring to piece together the history of prehistoric man 'from specimens of his handiwork that have been heir- loomed to us by the 'sheltering hand of Nature, who has protected them for us, either by covering them over with the ddbris of rock or hiing them under stalagmite or in the deep breccia in the floors of caverns. To this has been added a ■passing glimpse at the methods of present-day primitive tribes. Tylor says (18) “ The uniformity which so largely pervades civilisation may be ascribed, in large measure, to the uniform action of uniform causes.” Thus it is that the combination of these two parallel studies enables us to get a true insight into the life of prehistoric days. For a moment let us look forward, far into the future, to the day when cancer will no longer be a terror, when tuber- culosis will be a rare or unknown disease, and v.hen lymphadenoma and lymphatic anaemia will be understood and preventable. In these halcyon days the advanced medical-scientist, when looking back on the opening years of the twentieth century, will state that radium had only just been discovered, electricity was only used In a limited manner, and that scientists of that day were only then wresting hypnotism from the hands of the shrewd and clever charlatan. They will possibly look back upon these days as we now look back upon the Age of Stone. May they ibe as gently critical upon us and our methods as we feel towards prehistoric man and his early efforts to combat disease. KEFEREXCES. (1) “Pratt’s British Grasses,” pp. 69. 125 (2) “The Ortgia and Growth of the Healing Art.” By Edward Berdoe. (3) “Antidote to Atheism.” By More. (4) “History of Medicihe from the Earliest Times.” By Withington. (5) “Life of Cornelius Agrippa ” (Occult Philosophy), Vol. I., p. 129. By Morley. (6) “ The Vanishing Race.” By Dr. Joseph K. Dixon, p. 12. (7) Psalms of David, xxxvii., 13. (8) Journ. Ind. Archip., Tol. III., p. 110, Vol. IV., p, 194. (9) “Folk Medicine,” p. 3. (10) “Folk Medicine,” p. 11. (11) Ency. Brit., Vol. IV. p. 58. (12) “ The Land of the Pardons. By Anatole Le Braz. p. 4. (13) “Trepanation Neolithique,” par Broca (1912). (14) Journ. Anthropolog. Instit. Vol. XI. pp. 7-21. By Buck- land. (15) “Sur la Trepanation du Crane et les Amulettes Craniennes h i’Epoque Neolithique.” Par M. Paul Broca. 1877. pp. 69, 70. (16) “Excavations in Cranbourne Chase.” By Lieut.-Gen. Pitt.- Eivers. Vol. III. Plate 227. (17) “Trepanation Neolithique, Trepanation Pre-Colomhienne, Trepanation des Kabyles, Trepanation Traditionelle.” Par le Dr. Lucas-Championniere. 1912. (18) “ The Master Girl.” By Ashton Hilliers. p. 87. (19) “Primitive Culture.” By Dr. E. B. Tylor.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b22463902_0012.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)