Prehistoric man and his early efforts to combat disease / by T. Wilson Parry.

- Parry, Thomas Wilson, 1866-1945.

- Date:

- 1914

Licence: In copyright

Credit: Prehistoric man and his early efforts to combat disease / by T. Wilson Parry. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by The Royal College of Surgeons of England. The original may be consulted at The Royal College of Surgeons of England.

7/12 (page 5)

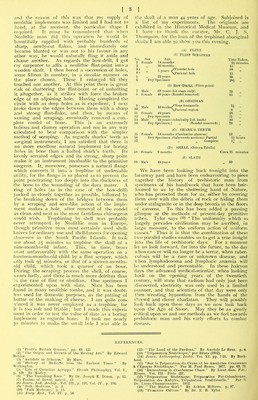

![St Blaise quinsy and bones sticking in the throat, St. Erasmus colic, and so on indefimitely. It must have been but a short step for the first man who, firmly believing in demoniacal possession, and at the same time suffering either from frequent fits, severe pain in the head of a periodic or paroxysmal nature, chronic hemi- crania, or unbearable M^ni^re’s disease, made an effort to free himself from his fetters. Life had become an intolerable burden to him, and he believed that there was a devil inside his cranium that was pebitioning somewhat persistently 'for liberty. Was there not the Medicine-man who jilways attended to members of his tribe when accidents befell them, who stopp'fed their bleeding and dressed their wounds? He would go to him and ask him to malce a hole in his skull to let out this wicked and restless spirit. The first opera- tion must have been troublesome and tedious, not to mention its extreme danger. The scalp had to be cut through with a sharp piece of flint or obsidian, the bleeding stopped, and the scraping of the bone commenced. This would take the first operator many hours to perform, but the patient was helpful and anxious to get rid of bis devil and possessed that unflinching stoicism to pain that is characterisbic of the savage and the operation would be at length completed. If the patient recovered, whether he obtained relief from his symptoms or not, he was henceforth reverenced as a sacred person. We can thus see why, in some districts, trephining was so prevalent, for prestige seems to have been purchased by undergoing this operation. After death the skull was eagerly- sought after. The trephined portion was removed by flint saiws, and pieces of 'bone, edged by part of the healed cicatrix, were removed. A hole was bored through the centre of this trophy, and it was henceforth regarded as a talisman that if worn would insure the wearer from getting the disease from which the operatee had suffered. So great a demand appears to have been made for these amulets, at one time, that we actually find spurious imitations were made, some fashioned from horn, and others made from untrephined pieces of bones, so that a portion of the healed cicatrix became an essential to prove its authen- ticity. The year 1868 was a memorable one, for it was in this year that M. Prunieres discovered in a dolmen near Aiguieres the first trephined neolithic skull to which the attention of scientists was drawn. A large piece of bone had been removed, and the smoothness of the edges made the_ discoverer think that this had been purposely polished for the lips, in the converting of the skull into a drinking-cup, a practice well recognised among savage tribes. The finding of five other skull fragments, in the same dolmen, all partially polished in the same way, made the finder think that these also were parts of converted dninking- cups. The interpretation of this mystery wias left to Professor Broca, who showed indubitably that tne^holes in the skulls had been made duriing life, had been done by scraping, and that, alfter the death of the individual, portions of such skulls had been evidently eagerly sought after. He came to the conclusion that the operation was usually performed on children and from what he says: (13) it could be effected on the skull of a child in less than five minutes, whilst on an adult it would take an hour,”—it will show he had probably made some careful experiments. Broca believed that the operation was performed for the cure of epilepsy and convulsions, and he argues from the sup<T- stitious practices found in connection with it that at tliat ]>eriod, as well as long subsequently, these dl.t-eascs were regarded as iiecuJiarly the work of spirits. He quotes from a troatisn upoia epilepsy (H) by Jelian Taxil published in 1603 not only to show tliat infantile con-vulsiions were confounded with true epilepsy, but that, at that time, epilepsy and kindred diseases were looked upon as spiritual diseases, the works of gods or demons, while the remedies recom- mended in the treatise were highly suggestive, -con- sisting som-etimes o-f the aishes of a human skull applied as a plaster on the crown of the head, some- times the same admiinistered in potions or pilules, and sometimes as nodules to be worn, round the neck; while sometimes also scraping the skull was recommended. Broca goes on to show that (is) “ all through the middle ages, and even after the Renaissance, the substance of the human skull was used in the treatmen:t o-f epilepsy, the skulls of Egyptian mummies being regarded as the most efficacious; whilst in the last century all t'he pharmacies contained a bottle labelled ‘ Ossa Wormiana ’ for the treatment of epilepsy, the j)ec-uliar efficacy of the triangular lambdoidian bone consisting in its form, which resembles that of the amulet cut from the human sicull, thus show- ing the step between -propbyilactic and mystic m-edi- cine.” Broca thought that trephining was in vogue throughout the entire Neolithic Period on Figs. 6 and 7. Fig. 6, Skull of Male (68 years) trephined (ist stage only) by flint-pointed bo-w-drill (Fig. 2). Time taken 25 minutesi. Fig 7, Skull of infant (9 months) trephined by oyster shell (Os-troea Edulis). Time taken 50 minutes. account of the fact that trephined skulls had been found in the cavern of the “Hommie Mort ” (IxDz^re) which dates from the commencement of the Neolithic Period. 'It might have been thought, considering the numiber of trephined skulls that have been e.x-cavated in France, that the custom would have -spread to the British Isles, as only the Channel separated the two countries, and we have evidence that there was no inconsiderable traffic between them in Neolithic times. I have only been able to hear of three such slculls that h-ave been unearthed in this oo-untry, and I should -be most happy if anyone knowing of any other specimens would kindly inform me. The three speaimens of which I know are: (a) A skull that was dredged from the bottom of the docks at Port Talbot, South Wales, in or about 1870-2. I have a photograph of this skull to show you this ovening, kindly lent me by Mr. Thomas Gray of the above-mentioned place. This skull shows a frontal excavation over the right su-pra-orbitial region. Not having .se-on the .specimen I am unable to give any oiilnlon. (h) An interesting specimen showing a ring-lre-phlne a.s if an effort had been made to remove a rondel of bone. 'Phis specimen was e.xc.avated in the autumn of 1863 from a long barrow, near Bisley, by the late](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b22463902_0009.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)