Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: On the prevention of consumption / by Arthur Ransome. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by The Royal College of Surgeons of England. The original may be consulted at The Royal College of Surgeons of England.

21/24 page 19

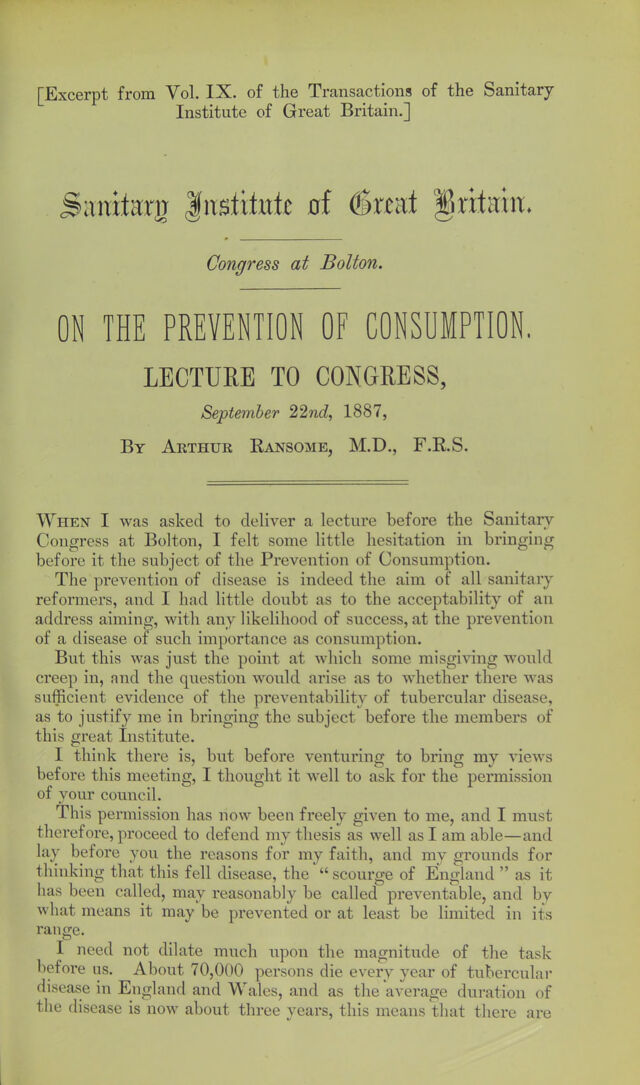

![How, then, can these facts be reconciled with the overwhchning evidence that air rendered foul by respiration is one of the most powerful agents in producing consumption. The explanation given by Dr. Koch is (1) the need for some preliminary injury to the lungs in persons who are about to act the part of hosts to these parasitic organisms, some denudation of the mucous membrane of the lungs, or some injury to the elasticity of these organs; and (2) the need of a plentiful supply of the infecting material. The number of these microbes contained in the breath, even in advanced cases of phthisis is, as I can testify from repeated examinations, exceedingly small; but, on the other hand, the dried sputum from such patients contains them in enormous quantities. This sputum is not only ejected directly on to the floor, there to be dried up, to be pulverised, and to rise again in the form of dust, but a good deal of it dries on bed linen, articles of clothing, and especially pocket-handkerchiefs, which even the cleanliest of patients cannot help soiling with the dangerous infective material when wiping the mouth after expectoration ; and this also is subsequently scattered as dust. I am doubtful myself how far this explanation would account for the exem])tion of the attendants of consumption hospitals from disease, and still more for the immunity conferred by residence upon well-drained porous soils. It affords no reason for the diminution in the phthisis rate of Salisbury, for instance, by one half, after the introduction of proper drainage, and I am therefore inclined to believe that we have still not attained to a complete knowledge of the natural history of the microbe, and to venture the hypothesis that it may gain in virulence by a short sojourn outside the body, in the presence of organic compounds favourable to its existence, and contained either in impure ground air or else in air rendered foul by respiration ; experiments need to be made on this point. In this case the bacillus of tubercle would fall into the same category as the microbe of enteric fever and cholera, and whilst scarcely at all infective from person to person, it would gain the power of reproducing the disease by a sojourn for a shorter or longer time in some medium favourable to its development. If high temperatures are absolutely needed for its existence I am inclined to think that it would find them in some nook or corner in the common kitchens and living rooms inhabited by many of the poor inhabitants of our towus. It is possible that all the components of expired air except the oxygen may take part in sustaining the existence of the microbe. I do not know whether the action upon it of carbonic acid has yet been ascertained, but it seems probable, from its continued existence in decomposing fluids, that it is one of](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b22302451_0023.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)