Licence: In copyright

Credit: Manual of surgery / by Alexis Thomson and Alexander Miles. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. The original may be consulted at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

51/856 (page 23)

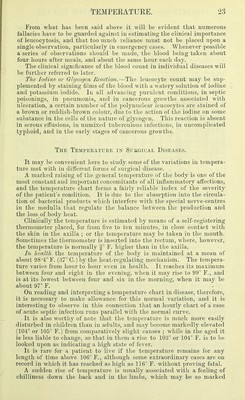

![From what has been said above it will be evident that numerous fallacies have to be guarded against in estimating the clinical importance of leucocytosis, and that too much reliance must not be placed upon a single observation, particularly in emergency cases. Whenever possible a series of observations should be made, the blood being taken about four hours after meals, and about the same hour each day. The clinical significance of the blood count in individual diseases will be further referred to later. The Iodine or Ohjeogen Reaction.—The leucocyte count may be sup- plemented by staining films of the blood with a watery solution of iodine and jiotassium iodide. In all advancing purulent conditions, in septic poisonings, in ])ueumonia, and in cancerous growths associated with ulceration, a certain number of the jiolynuclear leucocytes are stained of a brown or reddish-brown colour, due to the action of the iodine on some substance in the cells of the nature of glycogen. This reaction is absent in serous effusions, in unnuxed tuberculous infections, in uncomplicated typhoid, and in the early stages of cancerous growths. The Temperature in Surgical Diseases. It may be convenient here to study some of the variations in tempera- ture met with in ditl’erent forms of surgical disease. A marked raising of the general temperature of the body is one of the most constant and important concomitants of all inflammatory affections, and the temperature chart forms a fairly reliable index of the severity of the patient’s condition. It is due to the absorption into the circula- tion of bacterial products which interfere with the special nerve-centres in the medulla that regulate the balance between the production and the loss of body heat. Clinically the temperature is estimated by means of a self-registering thermometer placed, for from five to ten minutes, in close contact with the skin in the axilla ; or the temperature may he taken in the mouth. Sometimes the thermometer is inserted into the rectum, where, however, the temperature is normally |° F. higher than in the axilla. In health the temperature of the body is maintained at a mean of about 98'4°F. (37° G.) by the heat-regulating mechanism. The tempera- ture varies from hour to hour even in health. It reaches its maximum between four and eight in the evening, when it may rise to 99° F., and is at its lowest between four and six in the morning, when it may be about 97° F. On reading and interpreting a temperature chart in disease, therefore, it is necessary to make allowance for this normal variation, and it is interesting to observe in this connection that an hourly chart of a case of acute septic infection runs parallel with the normal curve. It is also worthy of note that the temperature is much more easily disturbed in children than in adults, and may become markedly elevated (104° or 105° F.) from comjiaratively slight causes ; while in the aged it is less liable to change, so that in them a rise to 103° or 104° F. is to be looked uiion as indicating a high state of fever. It is rare for a patient to live if the temperature remains for any length of time above 106° F., although some exti'aordinary cases are on record in which it has reached as high as 116° F. without proving fatal. A sudden rise of temperature is usually associated with a feeling of chilliness down the back and in the limbs, which may be so marked](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21933194_0001_0051.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)