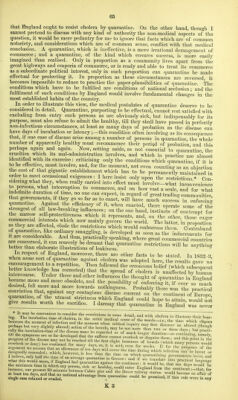

Plague : papers relating to the modern history and recent progress of Levantine plague / prepared from the time to time by direction of the president of the Local Government Board, with other papers ; sented to both House of Parliament by Command of Her Majesty.

- Radcliffe, Netten.

- Date:

- 1879

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Plague : papers relating to the modern history and recent progress of Levantine plague / prepared from the time to time by direction of the president of the Local Government Board, with other papers ; sented to both House of Parliament by Command of Her Majesty. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by Royal College of Physicians, London. The original may be consulted at Royal College of Physicians, London.

67/82 (page 61)

![questions of fact which so many years ago ,were in dispute; but, so far as the state- ments are accepted in proof of the communicability of yellow fever by personal inter- course, the acceptance must be qualified with the same considerations as I have expressed in regard of the corresponding statements at St. Nazaire.* In the thirteen vears which have elapsed since the occurrences in question, persons, more or less ill with yellow fever, have on numerous occasions been landed at Southampton from West Indian steamers; but in no case, so far as my information extends, has it even been suspected that their disease has spread to other persons. Nor did anything of this kind arise in connexion with the above-mentioned case of the engineer who ran the whole course of his disease in Southampton. The various incidents to which the last preceding pages have been given possess in Question of common one particular kind of interest. Por, when the public mind is troubled Avith Contagion in facts or rumours of epidemic visitation, question always arises how far the mischief [j*|g^p°^jj^ can be stopped or prevented by restrictions on the ordinary freedom of traffic, national pieaith. or international. And since the present report records the coincidence of several cases wherein that question was raised, it may be convenient that I here briefly state the principles on which such cases have been considered. When phenomena of pestilence are under popular discussion, and most of all when quarantine is being spoken of, frequently language is used which seems to imply a belief that the medical profession is divided as it were into two camps, respectively of *' contagiouists and anticontagionists. Now, so far as my knowledge extends, I will venture to say (speaking of course of the medical profession as represented by its acknowledged teachers) that no such duality of opinion exists. That many of our worst diseases acquire diffusion and local perpetuity by means of specific infective influences which the sick exercise on the healthy is an elementary truth of medicine; and among persons who are competent to distinguish the certainties from the uncer- tainties of science, there is no more doubt, broadly, as to that truth than there is doubt as to the dim-nal and annual movements of the earth.f Ambiguities which fifty years ago existed in respect of some particular cases have since then been gradually cleared away;—sometimes through the ascertainment that seeming contra- dictions of fact were facts of different diseases confounded under a common name;J sometimes through the new and conclusive evidence of' well recorded cases and expe- ments ; § sometimes through improved insight into the habits of a morbid poison; \\ and generally through that better grasp which time has given us of the subject as a whole. And more and more the once chaotic phenomenology of contagion is tending to become an intelligible and consistent section in the great science of organic chemistry. On the other hand, not even the merest tiro in medicine supposes that contagion (as a morbific power acting from each sick centre) operates equally on all persons, or equally under,all varying circumstances of place and time. Differences are obvious even to superficial observation, and such differences become still better appreciated as the general doctrine of contagion gets to be better understood. Pirst, as regards personal differences of susceptibility ;—they are seen, on a small scale, when we observe with what different degrees of severity different persons and different families in similar external circumstances, and with similar exposures to • contagion, suffer the diseases which they thus contract;—and, on a much larger scale, the same thing is seen in that permanent and complete insusceptibility which most persons acquire in relation to certain contngia which have once affected them : to small-pox, typhus, and measles, for instance : so that millions of persons who have * Sec Foot-note (*) at pp. 59, 60. ■j In my sixtli annual report, when discussing the subject of the spread of communicable diseases in hospitals, I stated with some detail, and need not now again state, the very different conditions under which dillerent diseases are communicated. See Report for 1863, p. 53. f Well, for instance, might there be difference of opinion about the communicability of continued fever, while under that name typhus, typhoid, and relapsing fevers were all spoken of as one disease. So, too, in regard of syphilis, the old uncertainty as to the laws of the contagion depended in great part on confusion between two kinds of chancre. § Such, for instance, as those by Avhich the contagiousness of typhoid fever and of cholera has been estab- lished. II As for instance, in the knowledge which has been got as to the great derelo])ment of contagious property in choleraic discharges some two or three days after their discharge from tlie body ; or the knowledge of the different effect which one kind of syphilitic inoculation exercises on those who have, and those who iiave not, previously suffered from a like inoculation. i<* K 645. K](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b24751388_0069.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)