Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The atmosphere in relation to human life and health. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the Augustus C. Long Health Sciences Library at Columbia University and Columbia University Libraries/Information Services, through the Medical Heritage Library. The original may be consulted at the the Augustus C. Long Health Sciences Library at Columbia University and Columbia University.

127/166 page 115

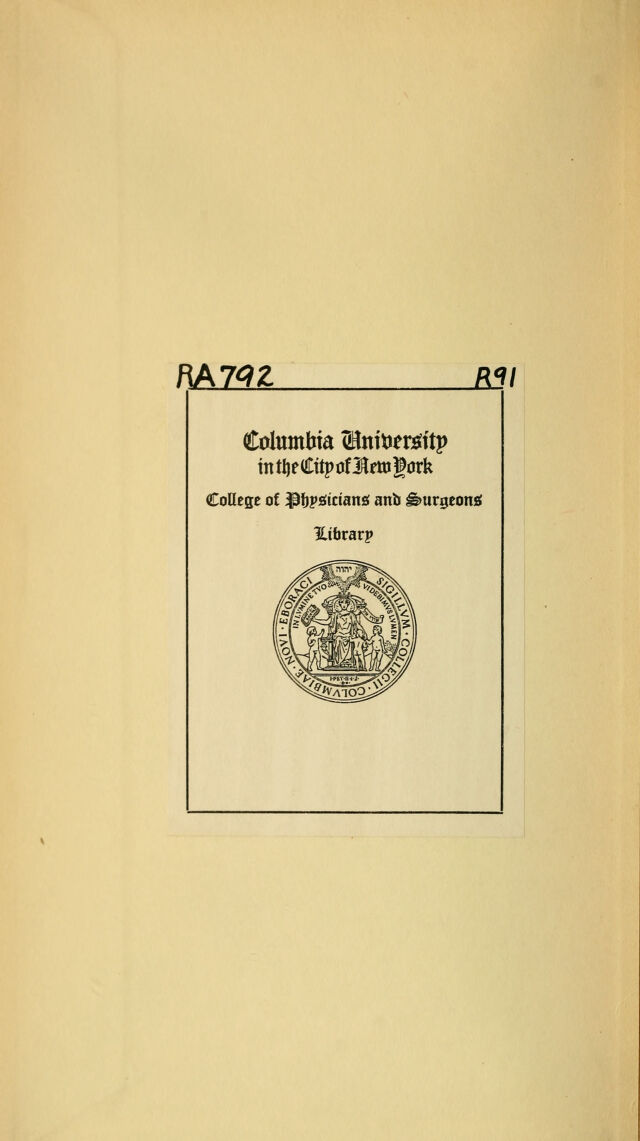

![on the capacity of tlie atmosphere for modifying and absorbing the radiant energy of the sun. An investigation of the principal elements concerned in arresting and reflecting the sun's rays would yield results of much interest. Tlio iil»sor])tive and reflecting capacity of vapor in the free air has not been il( termined. The power of any constituents of the air, e. g., ozone and ammonia, apart from dust particles, to scatter the rays of light, is not known. The reasons of the variations in radiation from the surface of t lie earth on different days when the weatlier continues clear and appar- <iitly unaltered have not been fully made out. Much information might 1m' gained by regular observation at two stations, one on the summit of a liigli mountain and one on the plain below, of the radiation value by (lay and night, and by comparing the results with the weather, humidity, and any meteorological phenomena which might be connected with Miern. Thus, for instance, a comparison of the radiation from the sta- tinns on two clear days, one dry and the other iuimid, would give some idea of the effect of invisible vapor in arresting radiation. If true \ apor in a dry state is found in the laboratory not to stop heat rays, the inference would have to be made that vapor in the air often exists in a different but still invisible condition. WINDS AND TEMPERATURE AT GREAT HEIGHTS. Balloon observations have shown that a variety of currents are often met with in ascending from the earth to 10,000 or 20,000 feet, and also remarkable changes of temperature, not always in the direction of ccAJd. On September 15, 1805, the air near the earth was 82°, and at 23,0Cl0 feet was 15°. On July 27, 1850, after passing through a cloud fully 15,000 feet thick, 17.1° was noted at 19,685 feet, and —36.2^ at 23,000 feet. On July 17,1862, at 10,000 feet, 26°; at 15,000 feet, 31° j at 19,000 !( et, 42°; then a little below this beiglit only 16°. Thus it seems that tlie air maybe not seldom divided into adjacent masses differing by L'tr^ or more. On March 21, 1803, up to 10,300 feet the wind was east, 1»( tween 10,300 and 15,400 feet, west; about 15,000 feet, northeast; higher still, southwest, and from 20,600 to 23,000 feet, west. The changes of humidity are also sudden and great. Eain falls sometimes 4.000 feet above falling snow, at 15,000 feet. At 37,000 feet the dryness of the air indicated an almost entire absence of vapor, yet cirri lloated high above this altitude. On July 27, 1850, the balloon passed through about 7,000 feet of ice-cold water particles, and ice needles formed only at —10°. On March 21, 1893, a small balloon with regis- tering apparatus was sent up to a height much greater than any of which there was previous record, and a temperature of—51° C. was recorded at about 45,500 feet; the air at Vaugirard at the time being at 17° C. This very promising experiment of sending recording bal- loons to great altitudes seems likely to lead to valuable information on the condition of the air up to 50,000 or 60,000 feet m various kinds of weather.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21208724_0127.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)