Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The atmosphere in relation to human life and health. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the Augustus C. Long Health Sciences Library at Columbia University and Columbia University Libraries/Information Services, through the Medical Heritage Library. The original may be consulted at the the Augustus C. Long Health Sciences Library at Columbia University and Columbia University.

46/166 page 34

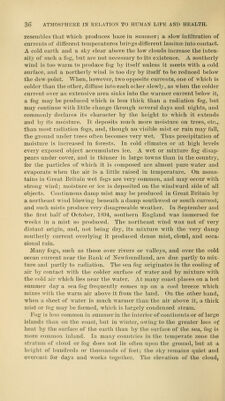

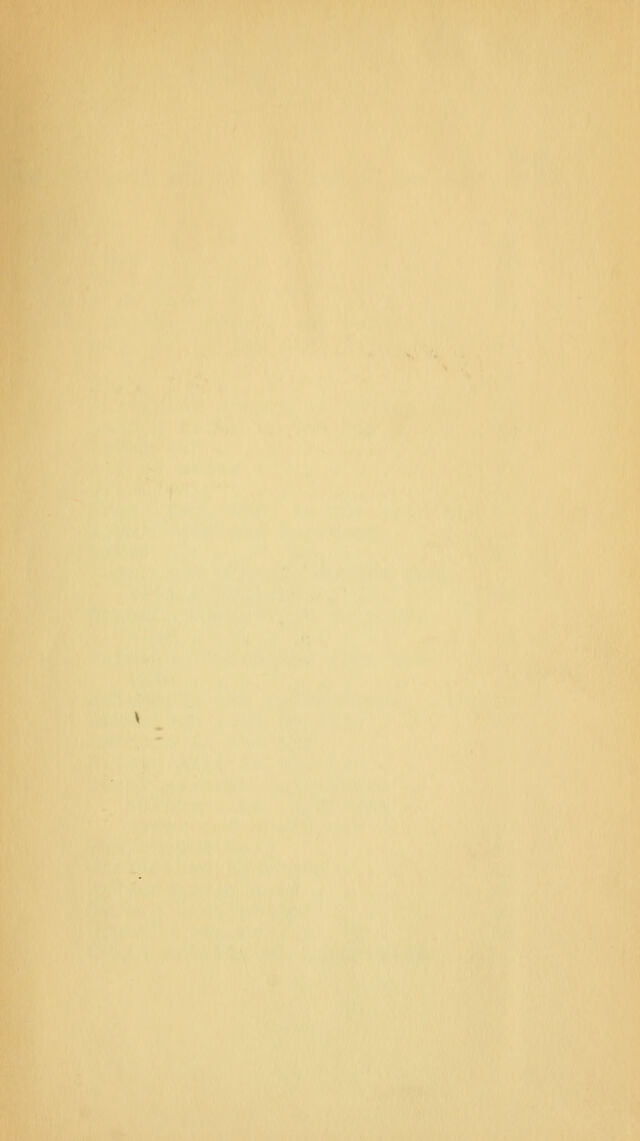

![At a distance of 10 miles from London, tlie smoky particles are small and slio\v quite a tliick haze in a room with a fire, wlieu a geutle cur- rent is moving from tlie town. Professor Frankland lias shown that if a little smoky air be blown across the surface of water evaporation is retarded 80 ])er cent. The water globules may be similarly coated with tarry matter, which hinders the warmth of the sun from evaporat- ing them. Moreover, every i:)article of carbon is a good radiator and in the early morning tends to increase the cold in the air around it; moisture is deposited upon it, in the opinion of the present writer, and can only with difficulty evaporate, so long as radiation is active and while the heat and light of the sun are stopped by smoke. The efi'ect of finely divided carbon in stopping light may be tested by holding a piece of glass for a few moments above the flame of a candle; the black film deposited enables us to look at the sun easily, and it appears well defined, like a red orange, as in a fog. The imperfect combustion of coal is the cause not only of fogs being specially dangerous to life, but of their persistence in duration far beyond those of the surrounding country. The removal of coal smoke would mean much less fog and much less evil in that w^hich remained. Cities which use wood as fuel, or anthracite, or gas, or oil, are no more visited by fogs than the surrounding country, although the fine dust above them is, according to Aitken, very greatly in excess of the normal. Pittsburg had a black climate till it used natural gas, and thencefor- ward has had a clear air, and no special liability to darkness and fog. In London, of 9,709,000 tons of coal used annually, about 1 per cent escapes into the air unburnt and 10 ijer cent is lost in other volatile compounds of carbon. The bright sunshine, compared with that of Kew, 9 miles distant, was, in the four years 1883-1886, 3,925 hours, against 5,713 at Kew, and about G,880 at St. Leonards, about 80 miles distant. From November, 1885, to February, 1886, inclusive, the sun- shine in London was 62 hours, at Kew 222, and at Eastbourne 300. Town fogs contain an excess of chlorides and sulphates, and about double the normal, or more, of organic matter and ammonia salts. During the last fortnight of February, 1891, the previously washed roofs of the glass houses at Chelsea and Kew, the former just within, and the latter just outside, London, received a deposit from the fog, which was analyzed and gave the following results: Substances. Carbon Hydrocarbons Organic bases (pyridines, etc.) Sulpburic acid (fiOs) Hydroclilorio acid (HCE) Ammonia Metallic iron and magnetic oxide of iron ilineral matter (chieliy silica and ferric oxide) Water, not determined (say difference) Cbclsea. Kew. Per cent. 39 Percent. 42.5 12.3 4.8 2 4.3 4 1.4 .8 1.4 i.l 2.0 31.2 41.5 5.8 5.3](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21208724_0046.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)