Some account of the last yellow fever epidemic of British Guiana / by Daniel Blair ; edited by John Davy.

- Date:

- 1850

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Some account of the last yellow fever epidemic of British Guiana / by Daniel Blair ; edited by John Davy. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. The original may be consulted at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

40/222 (page 20)

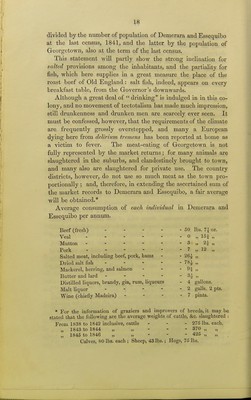

![The water in general use is rain water, collected in vats, tanks, and cisterns, from the roofs of houses. It shows a slight impregnation of marine salt. Artesian well water is used by the poor in droughts. It is highly chalybeate, and very un- pleasant till it has deposited its iron.* In the country districts the negro population frequently drink trench water, or the rain water which is collected in ponds. All such water the agri- cultural chemist of the Colony, Dr. Shier, has found to have an alkaline reaction. In times of extreme drought, and in cases where the artesian well water is disliked, creek or river water, taken beyond the influence of the tide, is sometimes used. The sailors frequently carry home with them a supply from this source. The woodcutters of the rivers and creeks use this water; it is used also by the inhabitants of the penal settlement on the banks of the Cayuni (Essequibo). It is black, like bog water, from the large amount of vegetable extractive it contains, and always purges those unaccustomed to its use. After being used some time it is liked. As there is no limestone rock in British Guiana, and scarcely a trace of lime in the alluvial soil except here and there where a shell bank occurs on the -fore shores, there is none of this earth in the water drunk by any of its inhabitants. The diseases from which the colonists are entirely free, are contagious or infectious fevers (except the exanthemata), cal- culus, diabetes, rabies: those from which they are nearly exempt? a fruglvorous wild quadruped, much prized for the fatness and delicacy of its flesh. The author's remarks on diet would seem to imply that the appetite is as keen, and that as much food is required to satisfy it and support the organic waste, in British Guiana, as in a cool or cold climate. This, however, I be- lieve; is not the case: according to the best information I could obtain in the AVest Indies, the proportion of nourishment essential to health there is decidedly less than in England and more northern regions. It must be kept in mind that the food most in use within the tropics is of low nourishing power, such as arrow-root, cassava, and the other farinaceous articles; whence, perhaps, the craving, especially for solid food, and the fondness for salt fish.] — Ed. * [In the water of the artesian well at' Port Mahaica, Demerara, I have found common salt in minute proportion, with a trace of sulphate of lime and of sulphate of magnesia. It moreover contained, suspended in it, subsiding on rest, a very little peroxide of iron, attached to delicate fibres of mucor : a high power of the microscope was required to exhibit these. The author informs me that alkaline carbonates are commonly found in the water of these wells and carbonate of iron, the latter dissolved by carbonic acid, a gas usually abounding in it before exposure to the atmosphere.] —Ed.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21976077_0040.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)