Contributions to Egyptian anthropology : tatuing / by Charles S. Myers.

- Charles Samuel Myers

- Date:

- [1903?]

Licence: In copyright

Credit: Contributions to Egyptian anthropology : tatuing / by Charles S. Myers. Source: Wellcome Collection.

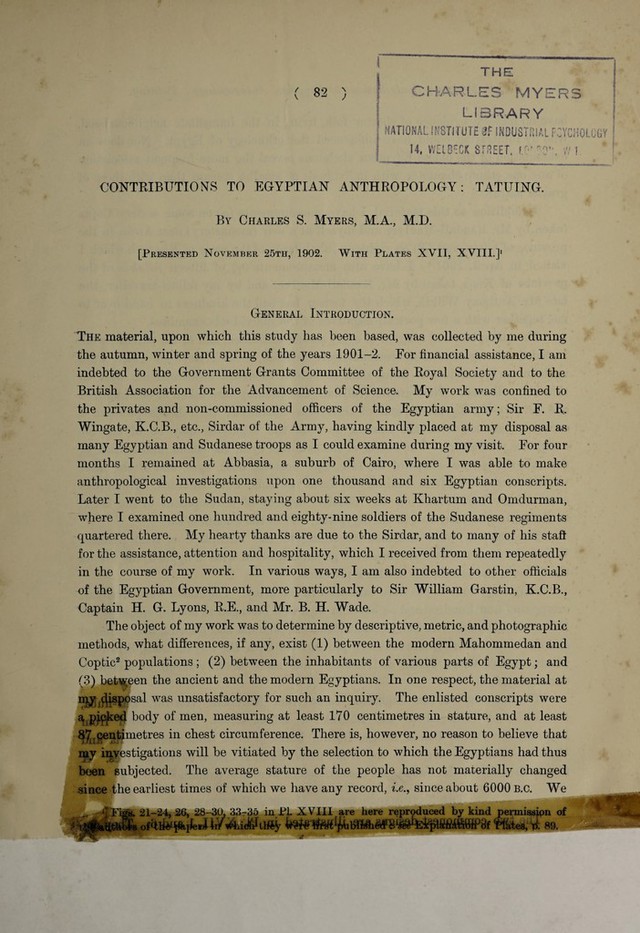

10/16 page 89

![three-stemmed plant; but, when inverted, it is singularly like a device (PL XVIII, 21) met with on a ring from the Vapheio tomb near Sparta, which, it has been conjectured, is derived from the well-known Egyptian symbol, the Ankh. Again, the lioopoo, according to Wilkinson, was never a sacred bird in ancient Egypt, although it seems to have been “ respected.” In Palestine and Arabia, on the other hand, it was an object of great veneration. The hoopoo (mistranslated “ lapwing ” in the authorized version) was one of the forbidden articles of food among the Hebrews (Lev. xi, 19 ; Deut. xiv, 18). It was sent by Solomon to interview the Queen of Sheba, according to the late Jewish legend, incorporated by Mahommed into the Koran (chap. 27, “ The Ant ”). At the present day, the “ Arabs ” of Palestine call the hoopoo the doctor, and its head is “ an indispensable ingredient in all charms.”1 In modern Egypt the heart of this bird has come to be used similarly for the curing of certain diseases. Lastly, the Egyptian tatu-pattern (PL XVIII, 25) may be compared with the Mesopotamian design (PL XVIII, 24). It appears, then, that the simpler and more purely geometrical patterns of modern Egyptian tatuing are akin to those which prevail throughout northern Africa, while the more complex have been derived from an Eastern source. Explanation of Plates. All the figures in Plate XVII, and Figs. 18, 19, 23, 25, 32, 36, in Plate XVIII, are speci¬ mens of modern Moslem Egyptian tatuing. The provenance of the various designs is here given, numbers in brackets referring to the card-numbers of the fellahin who were examined. Plate XVII, Fig. 1. Assiut (846) Plate XVII, Fig. 13. Fayum (884) 33 V) 2. Menufia (882) 31 13 14. Beheira (977) 33 33 3. Gharbia (802) 33 33 15. Dakahlia-Fayum 33 r> 4. Girga (625) (997) 33 33 5. Kaliubia • (908) 33 33 16. Alexandria(734) 33 n 6. Kaliubia (764) 33 33 17. Menufia (698) 13 73 7. Kena (858) Plate XVIII, 33 18. Dakahlia (889) 73 33 8. Fayum (859) 33 33 19. Beheira (981) 33 33 9. Beheira (977) 33 33 23. Kaliubia • (764) 3 3 • 33 10. l-Gharbia (986) 33 33 25. Menufia (304) 33 33 11. Beheira (981) 33 33 32. ? 1 3) 31 12. Menufia (703) 33 33 36. Assiut (647) In Plate XVIII, Figs. 27, 28, 31, were obtained from Copts. Fig. 31 had been tatued in Jerusalem. Fig. 28 was observed by Fouquet (loc. cit.). Figs. 26, 29, 30, are from an early Egyptian painted white clay figure, discovered by Petrie and Quibell (loc. cit.). Figs. 33-35 are from designs on Libyans from the tomb of Seti I (Rosellini, op. cit.). Fig. 20 is a design from a Chakhean contract. {Arch, des Missions Scientifiques, 1880; Tome vi, p. 94). Fig. 21 appears in a design on a gold signet-ring from the Vapheio tomb (A. J. Evans, Mycenean Tree and Pillar Cult, London, 1901, Figs. 52, 54). Fig. 22. Gold Shrine with Doves; Third Akropolis Grave, Mycense (from Schliemann’s Mycence ; here copied from A. J. Evans, op. cit., Fig. 65). Fig. 24. From a Mesopotamian cylinder {Collection de Clerq, tome i, pi. xxxi, Fig. 330 ; here copied from d’Alviella, Migration of Symbols, London, 1894, Fig. 140). 1 Rev. H. B. Tristram, The Ibis, 1859, vol. i, p. 27. [.Reprinted from the Journal of the Anthropological Institute, Vol. XXXIII, January-June, 1903.] Harrison and tSons, Printers in Ordinary to His Majesty, tSt. Martin’s Lane.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b30603481_0010.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)