On food : four Cantor lectures, delivered before the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce / by H. Letheby.

- Henry Letheby

- Date:

- 1868

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: On food : four Cantor lectures, delivered before the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce / by H. Letheby. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by The Royal College of Surgeons of England. The original may be consulted at The Royal College of Surgeons of England.

18/56 (page 16)

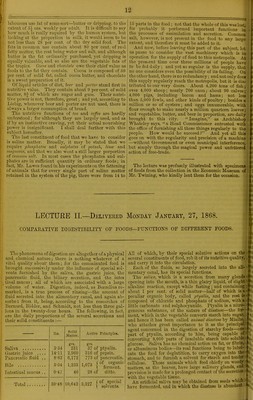

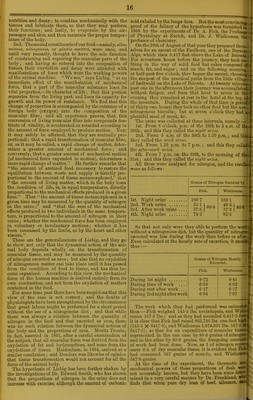

![nutrition and decay; to combine mechanically with the tissues and lubricate them, so that they may perform their functions; and lastly, to evaporate by the air- passages and skin, and thus maintain the proper temper- ature of the body. 2nd. The second constituents of our food—^namely, albu- minous, nitrogenous, or plastic matters, wore once, and until very recently, thought to have the sole function of constructing and repairing the muscular parts of the body; and having so entered into the composition of tissues, their oxydation and decay wore attended with manifestations of force which were the working powers of the animal machine. We see, says Liebig, as an immediate effect of the manifestation of mechanical force, that a part of the muscular substance loses its vital properties,—its character of life; that this portion separates from the living part, and loses its capacity for growth and its power of resistance. We find that this change of properties is accompanied by the entrance of a foreign body (oxygen) into the composition of the muscular fibre; and all experience proves, that this conversion of living muscular fibre into compounds des- titute of vitality, is accelerated or retarded according to the amount of force employed to produce motion. Nay, it may safely be afiirmed, that they are mutually pro- portional ; that a rapid transformation of muscular fibre, or, as it may be called, a rapid change of matter, deter- mines a greater amount of mechanical force; and conversely, that a greater amount of mechanical motion (of mechanical force expended in motion), determines a more rapid change of matter. He further remarks that the amount of azotized food necessary to restore the equilibrium between waste and supply is directly pro- portional to the amount of tissue metamorphosed, that the amount of living matter, which in the body loses the condition of life, is, in equal temperatures, directly proportional to the mechanical eflects produced in a given time. That the amount of tissue metamorphosed in a given time may be measured by the quantity of nitrogen in the urine; and that the sum of the mechanical effects produced in two individuals in the same tempera- ture, is proportional to the amount of nitrogen in their urine; whether the mechanical force has been employed in voluntary or involuntary motions; whether it has been consumed by the limbs, or by the heart and other •viscera. These are the generalizations of Liebig, and they go to show, not onlj' that the dynamical action of the ani- mal body depends wholly on the transformation of muscular tissue, and may be measured by the quantity of nitrogen excreted as urea; but also that no oxydation of nitrogenous matter can take place untU it has passed from the condition of food to tissue, and has thus be- come organized. According to this view, the mechanical force of the human machine is derived entirely from its own combustion, and not from the oxydation of matters contained in the food. For some time past there have been suspicions that this view of the case is not correct; and the doubts of physiologists have been strengtliened by the circimistance that great labour might be performed for a short period without the use of a nitrogenous diet; and that while there was always a relation between the quantity of nitrogen in the food and that excreted as uvea, there was no such relation between the dynamical actions of the body and the proportions of urea. Moritz Troube, in fact, asserted in 1861, after a careful examination of the subject, that all muscular force was derived from tlio oxydation of fat and hycbocarbons, and none from the oxydations of tissue. Hnidonham, in 1864, arrived at a similar conclusion ; and Bonders was likewise of opinion that tissue transformation would not account for all the force of the animal body. The hypothesis of Liebig has been further shaken bj' the investigations of Dr. Edward Smith, who has shown that the proportions of nitrogen in the urine docs not iacrease with exercise, although the amount of carbonic acid exhaled by the lungs does. But the most convincin , proof of the fallacy of the hypothesis was furnished i- 1866 by the experiments of Dr. A. Pick, the Profess , of Physiology at Zurich, and Dr. J. WisUcenus, th professor of chemistry. On the 29th of August of that year they prepared thpu selves for an ascent of the Faulhom, one of the Bemc- Alps, which rises 6,417 feet above the Lake of Brient/ For seventeen houi-s before the journey, they took ri< thing in the way of solid food but cakes composed > starch, fat, and sugar; and on the following momin, at half-past five o'clock, thev began the ascent, choosi^ the steepest of the practical paths from the little villa of Iseltwald on the Lake of Brientz. At twenty minu past one in the afternoon their journey was accomplisl without fatigue, and from that hour to seven in \ evening they remained at rest in the hotel at the top the mountain. During the whole of that time (a peri of thirty-one hours) they took no other food but the nc nitrogenous biscuits; but at seven o'clock they had plentiful meal of meat, &c. The urine was collected at three intervals, namely :• Ist. From 6 o'clock, p.m. of the 29th to 5 a.m. of i 30th; and this they called the night wine. 2nd. From 5 a.m. of the 30th to 1.20 p.m.; andt they called the woi'k tirinc. 3rd. From 1.20 p.m. to 7 p.m.; and this they cal] the after-worh urine. 4th. From 7 p.m. on the 30th, to the morning of i 31st; and this they called the night urine. All these were analysed for nitrogen, and the resn were as follows: Grains of Nitrogen Secreted Fick. WislicenusJ 3rd. After work urine .... 106-7 37-5 } ^^^ 74-3 103-1 j 37-3 1 ^ 82-5 So that not only were they able to perform the work without a nitrogenous diet, but the quantity of nitrogen excreted was less during the work than before or afbar. Even calculated at the hourly rate of excretion, it standi thus:— Grains of Nitrogren Hourly Excreted. Fick. Wisliccnus. During time of work .... Duiing rest after work.... During 2ndnightafterwork 9-72 6-33 6-17 6-94 9-41 6- 02 617 7- 87 The work which they had performed was cstiniat< thus:—Fick weighed 145-5 lbs. avoirdupois, and Wis! ccnus 167-5 lbs.; and as they had ascended 6,417-5 fw' it is clear that Fick had raised 933,746 lbs. one for ' ' • (145-5 X 6417-5), and Wislicenus 1,074,931 lbs. 1^ 6417-5); so that for an expenditure of muscular represented in the one case bj-88-6 grains of nit: and in the other by 85-6 grains, the foregoing anmui. of work had been done. Now, as 1 of nitrogen repr sonts 6-4 of dry muscular tissue, it is evident that Fif' had consumed 567 grains of muscle, and Wisliceni'. 547-8 grains. At the time of the experiment, the thermotic 8Jt mechanical powers of these proportions of flesh wfi not accurately known, but they have been since (let<r mined in a very careful manner by Dr. Frankland, wh finds that when pure dry lean of beef, albumen, ac 1](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b22280364_0018.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)