On food : four Cantor lectures, delivered before the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce / by H. Letheby.

- Henry Letheby

- Date:

- 1868

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: On food : four Cantor lectures, delivered before the Society for the Encouragement of Arts, Manufactures, and Commerce / by H. Letheby. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by The Royal College of Surgeons of England. The original may be consulted at The Royal College of Surgeons of England.

20/56 (page 18)

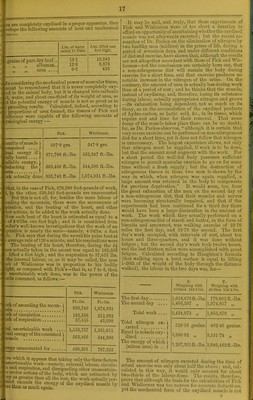

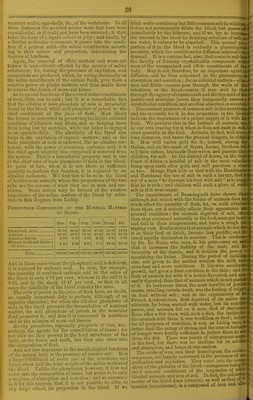

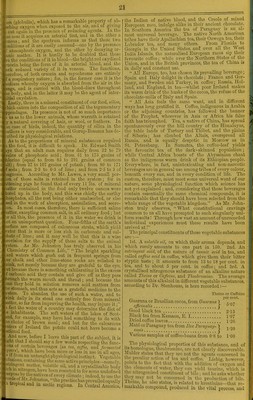

![sufficient to account for external and internal work; and tho conclusion is that, in tho above experiments, Ihe motive power of tlio muscles was not derived from their own oxydation of non-nitroR'cnous matters. Tho researches of Dr. Edward Hmith throw additional light on tho subjcefc, for he ascertained that tho amount of carbonic acid exhaled by tho lungs was in proportion to tho actual worlc performed. During sloop it was at tho rate of .. 293 grs. per hour. When lying down and approaching \ „.. sleep ■ / -^^^ In a sitting postiu'O 491 ,, ,, When walliing two miles an liour . 1,088 ,, ,, When walking three miles an hour 1,532 „ ,, And when woiliing at the treadmill 2,926 „ „ It is higlily probable, therefore, that the largest amount of muscular force is derived from the hydi'o-earbons of our food ; not that tho nitrogenous matters of it may not also bo a source of power; but there is no necessity, as Liebig supposes, for their being previously constructed into tissue. The experiments of Mr. Savory, in fact, show that rats can live and be in health for weeks on a purely nitrogenous diet, and it is nearly certain that under those circumstances the nitrogenous matters are mostly oxydised without entering into the composition of tissue. This, as I have said, is the main point of divergence from the hypothesis of Liebig; and it is further indicated by the fact that tho amount of nitrogen excreted is not in proportion to the work done, but to the quantity of it in the food, even when there is no muscular exertion. That the chief functions of nitrogenous matters is to repair tissue, there can be no doubt, for animals kept on a piu'cly carbonaceous diet quickly lose weight, and at last die from a disintegration of tissue ; but it is equally certain that the nitrogenous constituents of food have other ofhcos to perform. A daily diet of 21bs. of bread contains enough nitrogen to supply the mechanical wants of the system, but it will not maintain life. There is required an addition of animal food to render it sufficient for this purpose ; and indeed tho instincts and habits of the human race show, beyond all question, that a com- ; parativcly rich nitrogenous diet is necessary for the proper sustenance of life ; and it is very probable that it assists tho assimilation of the hydrocarbons. In this way it may help in the development of force without itself contributing directly to it; and this may serve to explain the fact, that there is a relation between the amount of nitrogen contained in the food and the labour value of it. Carnivorous animals are not only stronger and more capabl6 of prolonged exertion than herbi- vororous, but they are also fiercer in their disposition, as if force were superabundant. The boars of India and America, says Playfair, which feed on acorns, are mild and tractable, while those of the polar regions, which consume flesh, are savage and untamable; and taking instances of people—the Peruvians whom Pizarro found i j in the country at ils conquest, were mild and inoffensive I in their habits, and they subsisted chiefly on vegetable food ; whilst their brethren in Mexico, when found by Cortes, wore a warlike and fierce race, and tliey fed for tho mo.st part on animal diet. Tho miners of Chili, who work like horses, also food like them, for Darwin tells us that their common food consists of bread, beans, and roasted grain. Tho Hindoo navvies also who were employed in making the tunnel of tho Bhoro Ghat Itail- way, and who had very laborious work to perform, found it impossible to sustain their health ona vegetablodiet, and being left at liberty by their caste to cat as they pleased, they took tho common foo I of the English navigators, and wnro then able to work as vigorously. Abundant examples of this description—some of which will bi> further discussed as we p^oceRd, may be cited in proof I 1 of the direct relation of plastic food to mechanical work; ' ' but there is no proof that this material must first form tissue before its dynamical power can bo elicited. It is, however, a remarkable fact that all forma of nitrogenous food have not the same nutritive value; th' glutinous matters of barley and wheat, though alm^ identical in chemical composition, have very dift'or(;rii sustaining powers. It is the same with muscular flesh and artificially prepared fibrin and gelatine. Magendio found that dogs fed solely, for 120 days, on raw moat from sheep's heads, preserved their health and vig(; ■ during the whole of tho time ; but more than three tin. the amount of isolated fibrin, with the addition of muck gelatine and albumen, wore insufficient to preserve life. Wo may conclude, therefore, that although the main functions of nitrogenous matters are to construct and repair tissue, yet they have manifestly other duties to perform of an assimilative, a respiratory, and force- producing quality which are far from being understood. What do we know, indeed, of the actual modus operandi of tho nitrogenous ferments—ptyalin, pepsin, pancreatin, &c., which are secreted so abundantly into the alimentar'.- canal; or of tho conjugate nitrogenous compounds whi are present in the bile ? and how far have we advanc .^ in interpreting the functions of the nitrogenous constitu- ents of tea, coffee, mate, guarana, cocoa, &c., which tho instincts of mankind in every part of the globe have cvi- dently chosen for some physiological purpose? Tl; ■ same may be said of tho crystalline nitrogenous matt' of soup—as creatin, creatinin, inosic acid, &c., which can hardly be regarded as food.s, although they have powerful sustaining properties. But enough of this for tho present; and before leaving this part of the subject, I would direct attention to the fact, that nitrogenur matters when oxydised in the animal body never yio, . up the whole of their potential energy, for, by being c verted into urea, which is the chief product of th decay, there is at least a seventh part of their power lo in the secretion. It may be that this is a necessity arbing out of tho circumstance that if they were completely oxydised in the animal body and converted into carbonic acid, water, and nitrogen, the last-named gas would bt unable to quit the system, because of its insolubility in the animal fluids. Functions o f Faf.—The hydrocarbons which go by name of fat, differ from other hydrocarbons, as sugai* an* starch, in the circumstance that the oxygen is never sufficient quantity to satisfy the affinity of the hydi'Ogen and, therefore, fat is more energetic as a respiratory o: heat-producing agent. Its power, indeed, in this respect is just twice and a-half as great as that of starch o: sugar; for 10 grains of it will, by combining will oxygen, develop sufficient heat to r.iise 23'21bs. of wate one degree of Fahi-enhcit; and according to the deduc tions of both Joule and Meyer, this is equivalent to th' power of raising 17,9231bs. one foot high. In coli countries, where animal warmth is required, food rich ij fat is always preferred; and tho fat bacon of the Englisl- labourer contributes in no small degree to the productioi of mechanical foi-ce. But besides this, fat serves important functions in th: processes of digestion, assimilation, and nutrition. Ac cording to Lohmann, it is one of tho most active agent in the metamorphosis of animal matter; and this is see not merely in tho solution of nitrogenous articles of foo during digestion, but also in tho conversion of nutrier plastic substances into cells and masses of fibre. r.l> is#i long since observed that duiing the process of art:In i; digestion, tho solution of nitrogenous foods was considei ably accelerated by means of fat; and Lchmann ha since detemiinod, by actual ex])erimont on dogs, tlu albuminous substances deprived of fat remain longer i tho stomach, and require more time for their metamoi ])hosi8 tlian tho same substances impregnated with fii' It is probable, indeed, that the digestive power of Ui pancreatic fluid is duo in great measure to the prcsenf of fat; and that the subsequent chymification of foo< and its absorption into the blood, is greatly assisted b it. There is also good i-eason for believing that it : largely concerned in tho formation of bile, and that tt Ll](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b22280364_0020.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)