Volume 2

Chemistry, theoretical, practical, and analytical : as applied and relating to the arts and manufactures / by Dr. Sheridan Muspratt.

- James Sheridan Muspratt

- Date:

- [1860]

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Chemistry, theoretical, practical, and analytical : as applied and relating to the arts and manufactures / by Dr. Sheridan Muspratt. Source: Wellcome Collection.

114/644 (page 70)

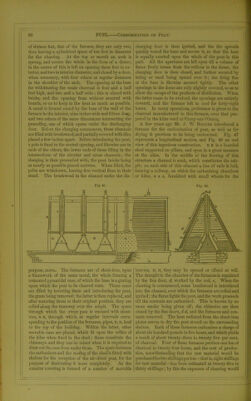

![FUEL Coai. Mkasukeb. in some degree equivalent to an .increased temperature, the moisture and excess of hydrogen would convert the remaining substance into carbonic acid and car- bides of hydrogen respectively. The actual facts, as determined in coal mines, seem to bear out this view. From such considerations it will be readily concluded that the elementary composition of coals must be different from ligneous fibre; but following up the assumed alteration by a symbolical representation, the composition of coal offers very conclusive grounds to warrant the opinion that the former has resulted from the latter in the manner indicated. For instance, the composition of woody fibre may, as already stated, be represented by the equation C,6 0K; and if, by the change above indicated, three equivalents of carbonic acid be extracted, represented by C3 06, there results Hon 0]6; and if from this one equivalent of hydro- gen be taken away, represented by H, there is left a formula—C33 H2l 016—corresponding with the com- position of a variety of coal worked in Laubach. In like manner the formula of splint coal may be deduced from the elements representing woody fibre, by supposing that the combined agency of heat and pressure removed nine equivalents of carbonic acid, three equivalents of water, and three of carbide of hydrogen, thus:— 1 Eq. of wood}' fibre, — ^36 H22 022 9 Eqs. of carbonic acid, = ^9 018 C.,7 H22 C>4 3 Eqs. of water, h3 03 C27 h19 o 3 Eqs. of carbide of hydrogen, .. • ^3 H8 .. Splint coal, C24 H13 0 According to the degree of force exerted upon the decomposing substance, and the period of time in which this change was taking place, it is evident that the substances would be more or less removed from one another in composition. In the first example stated above, the formation bears every indication of recent production, when compared with the second; and this accounts for the close analogy between the two for- mulae of wood and that species of coal. In other kinds, such as many of the anthracites, the alteration is much greater than even in the splint already referred to, and it is much more difficult to recognize the analogy be- tween them and wood, for often all the oxygen and hydrogen are removed, so that nothing is left but car- bon and the mineral matters intermixed with it. Coal —The region of the coal formations is very extensive, and includes many strata, all of which are known as the coal-meamrex, or carboniferous group. Properly speaking the first of these is what is termed the under-lay; this is, a tough argillaceous substance, which, upon drying, turns grey and becomes friable. It retains considerable traces of carbonaceous matters. Two other strata beneath this are, however, included in the group; these are the mountain limestone, which varies very much in thickness, being sometimes nine hundred feet, and the old red sandstone upon which it rests; the latter stratum ranges from two hundred to two thousand feet in thickness. Next to the underlay in the ascending scale comes the seam of coal, or mo- dified organic matter, varying from less than a quarter of an inch to several feet. Above these the upper layer or roof, as it is termed, rests. It is composed of slaty clay abounding in vegetal remains, as well as with crustaccae, and several other matters. Interstra- tified with the latter are found various other substances, which seem to have been accumulations drifted by cur- rents, such as laminated clay, grit, limestone, granite, sandstone, and other rocks. All these deposits at one time, doubtless, formed regular horizontal layers, but through the effects of expansion in the depths of the earth, they have been distorted and thrown into undulated positions, and where the internal force has been very great, they have, by the upheaval of the subordinate strata, been formed into large valleys or basins. From the position of these layers, previous to such convulsions occurring, it is obvious that as the older deposits of mountain limestone, old red sandstone, et cetera, emerged in suc- cession, so the more modern layers, including the car- boniferous, would appear at the surface. This appear- ance is termed the cropping out of the strata, and serves to indicate the side of the basin. Considerable irregularity is occasioned by further subterranean dis- turbances which tend to alter the position of the strata subsequently to the first upheaval of the older forma- tions. These generally render the deposits somewhat irregular in shape, so that they seldom form a true basin. In some localities, as in the Leicester and Warwickshire coal-field, none of the characters of a basin are observed; in the latter instance, the scams are surrounded on all sides by overlying deposits, under which they dip or incline to a considerable depth, and extend to an area unknown. Fig. 53 represents this field in section, showing tire alluvial deposits at a a ; the new red sandstone, or marls, at n n; the carboniferous shale and coal at cc, interlaid with carboniferous grit, or sandstones, dd; E, beds of magnesian; and K the stratum of mountain limestone, resting on the old red sandstone, G. Fig. 54 gives a faint idea of the disturbances which are occasioned in the various beds bv fissures tilled with other materials. These veins are, in the language of the miner, called dyke*, as they arc the means of separating the strata](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b28121132_0002_0114.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)