Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The anatomy of the human body / By J. Cruveilhier. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Lamar Soutter Library, through the Medical Heritage Library. The original may be consulted at the Lamar Soutter Library at the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

120/944 (page 96)

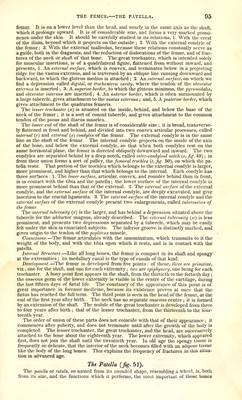

![which have been called sesamoid (from GTiffu/uTj), on account of their resemblance to the sesamum seed, and which are found in the neighbourhood of various articulations that are subjected to much pressure. It is situated in front of the knee, and is movable when the leg is extended ; but fixed and very prominent when the leg is flexed upon the thigh. Its mobility allows it to escape the injurious effect of external blows, to which it would be subject were it united to the tibia like the olecranon process to the ulna. It is the most variable of all the bones, both in its absolute size, and in the proportion of its different dimensions. It is flattened in front and behind, and presents an interior and a posterior surface, and a circumference. The anterior ox subcutaneous surfoxe {\,fig- 51) is convex, and covered by a very thick layer of fibrous tissue, intimately adherent to the bone. The posterior or femoral surface (2, fig. 51) corresponds exactly to the pulley on the lower extremity of the femur. We observe on it, 1. An articular ridge {x) sloping down- ward and inward, and corresponding to the groove of the trochlea, which presents the same obliquity. 2. On each side of this ridge, a concave articular surface, which is mould- ed upon the corresponding condyle of the femur; and as the external condyle of the femur is the larger, the external articular surface (y) of the patella is much greater than the internal. From this inequality, it is easy at once to distinguish the right from the left patella. The circumference of the patella resembles a curvihnear triangle; its thick base, di- rected upward, gives attachment to the tendon of the rectus femoris and to the tendons of the extensor muscles of the leg; and its apex {z), turned downward, and somewhat pointed, gives attachment to the ligamentum patellce. Its sides are thin, and give at- tachment to some aponeurotic fibres; so that, excepting its posterior surface, which is articular, the whole patella is enveloped in fibrous tissue ; a circumstance which is in ac- cordance with its peculiar mode of development, and has an important influence over its reunion when fractured. Internal Structure.—The patella is entirely composed of spongy tissue, covered in front by a thin layer of compact substance, which renders it very liable to fracture, and which forms a very remarkable exception to the generality of short bones, in presenting well-marked parallel vertical fibres. Between these fibres are numerous vascular open- ings. Development.—The patella is developed from one point only. In a few rare cases, as Rudolphi has observed, there are several points. The ossification of the patella com- mences about the age of two years and a half The IjEG. The Tibia {fig. 52). The tibia, the larger of the two bones of the leg, is situated between the femur, which rests upon its upper end, and the foot on which it is supported. Next to the femur, it is the largest and longest bone of the skeleton. Its upper extremity is expanded ; the shaft is narrower, and of a triangular prismatic form. The lower extremity is also ex- panded, but to a much less degree than the upper. The smallest part of the tibia does not exactly correspond with the middle of the shaft as in the femur, but at the junction of the lower with the two upper thirds ; and in this place fractures, produced by contre- coup, are most frequent. The direction of the tibia is vertical, contrasting thus with the femur, which, as we have seen, slants obliquely downward and inward. In individuals whose thigh bones are very oblique, the tibia? have a direction downward and outward. In a well-formed skeleton, the two tibiae are parallel. With regard to its axis, the tibia presents a double inflection, so that the upper end is turned outward and the lower slightly inward. When this last inclination is excessive, it gives rise to bowed legs. Lastly, it is slightly twisted at its lower part.* Like all long bones, it is divided into a body and extremities. The body or shaft has the figure of a triangidar prism ; and this form, which is observ- ed in almost all long bones, is in none so marked as in the tibia. W^e have, therefore, to consider three surfaces and three edges. The internal surface {a, fig. 53) is covered at the upper part by the internal lateral lig- ament, and by an aponeurotic expansion (called patte d'oic,^ or goose's foot): in the rest of its extent it is immediately under the skin. This superficial situation of the internal surface partly explains the facility with which this bone may be broken by direct violence, and also the frequency of caries, exostoses, and necrosis. It is broad above, and grad- ually diminishes towards the lower part. Its three superior fourths look inward and forward ; its lower fourth looks directly inward. The external surface {b) presents in a great part of its extent, but especially above, a longitudinal excavation, the depth of which corresponds to the size of the tibiaUs an- * The absence of an antero-posterior curvature and the lateral curves in opposite directions, together with its slight torsion, explains the great solidity of this bone. t [This patte d'oie consists of the expansion formed by the tendons of the sartorius, gracilis, and semitendi- nosus muscles.]](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21196801_0120.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)