Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The anatomy of the human body / By J. Cruveilhier. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Lamar Soutter Library, through the Medical Heritage Library. The original may be consulted at the Lamar Soutter Library at the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

203/944 (page 179)

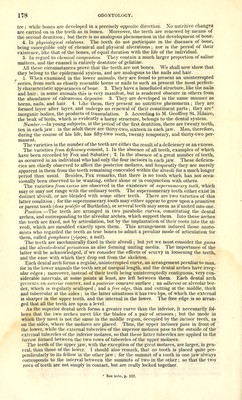

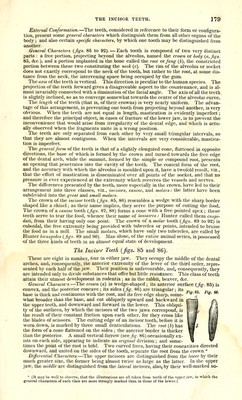

![External Conformation.—The teeth, considered in reference to their form or configura- tion, present some general characters which distinguish them from all other organs of the body ; and also certain specific characters^ by which one tooth may be distinguished from another. General Characters {Jigs. 85 to 92). — Each tooth is composed of tw^o very distinct parts : a free portion, projecting beyond the alveolus, named the crown or body (a. Jigs. 85, &c.}, and a portion implanted in the bone called the root or fang (b), the constricted portion between these two constituting the neck (c). The rim of the alveolus or socket does not exactly correspond to the neck of the tooth, but rather to the root, at some dis- tance from the neck, the intervening space being occupied by the gum. The asis of the teeth is vertical. This direction is peculiar to the human species. The projection of the teeth forward gives a disagreeable aspect to the countenance, and is al- most invariably connected with a diminution of the facial angle. The axis of all the teeth is slightly inclined, so as to converge somewhat towards the centre of the alveolar curve. The length of the teeth (that is, of their crowns) is very nearly uniform. The advan- tage of this arrangement, in preventing one tooth from projecting beyond another, is very obvious. When the teeth are not equal in length, mastication is evidently imperfect; and therefore the principal object, in cases of fracture of the lower jaw, is to prevent the inconvenience that would arise from irregularity of the dental edge, and which is actu- ally observed when the fragments unite in a wrong position. The teeth are only separated from each other by very small triangular intervals, so that they are almost contiguous. When the intervals are very considerable, mastica- tion is imperfect. The general form of the teeth is that of a slightly elongated cone, flattened in opposite directions, the base of which is formed by the crown and turned towards the free edge of the dental arch, while the summit, formed by the simple or compound root, presents an opening that penetrate* into the cavity of the tooth. The conical form of the root, and the accuracy with which the alveolus is moulded upon it, have a twofold result, viz., that the etfort of mastication is disseminated over all points of the socket, and that no pressure is ever experienced at the extremity which receives the vessels and nerves. The differences presented by the teeth, more especially in the crown, have led to their arrangement into three classes, viz., incisors, canhic, and molais: the latter have been subdivided into the great and small tnolars. The crown of the mci-sor teeth (figs. 85, 86) resembles a wedge with the sharp border shaped like a chisel; as their name implies, they serve the purpose of cutting the food. The crown of a cojiine tooth {figs. 87, 88) forms a cone with a free pointed apex ; these teeth serve to tear the food, whence their name of lamaires: Hunter called them cuspi- dati, from their having only one point. The crown of a 7nolar tooth (figs. 89 to 92) is cuboidal, the free extremity being provided with tubercles or points, intended to bruise the food as in a mill. The small molars, which have only two tubercles, are called by Hunter bkuspides {figs. 89 and 90). Man alone, of the entire animal series, is possessed of the three kinds of teeth in an almost equal state of development. TAe Incisor Teeth {figs, 85 and 86). These are eight in number, four in either jaw. They occupy the middle of the dental arches, and, consequently, the anterior extremity of the lever of the third order, repre- sented by each half of the jaw. Their position is unfavourable, and, consequently, they are intended only to divide substances that offer but little resistance. This class of teeth attain their utmost development in rodentia ; as in the rabbit, beaver, &c. General Characters.—The crown (a) is wedge-shaped; its anterior surface {fig. 85) is convex, and the posterior concave; its sides {fig. 86) are triangular; its _,. „, _. g, base is thick and continuous with the root, and its free edge sharp, some- ^' ,^ ^^' what broader than the base, and cut obliquely upward and backward in the upper teeth, and downward and forward in the lower. This obliqui- ty of the surfaces, by which the incisors of the two jaws correspond, is the result of their constant friction upon each other, for they cross like the blades of scissors. The cutting edge of an incisor tooth, before it is worn down, is marked by three small denticulations. The root {b) has the form of a cone flattened on the sides ; the anterior border is thicker than the posterior. A small vertical furrow (see fig. 86) occasionally ex- ists on each side, appearing to indicate an original division ; and some- times the point of the root is bifid. Two curved lines, having their concavities directed downward, and united on the sides of the tooth, separate the root from the crown.* Differential Characters.—The iipper incisors are distinguished from the lower by their much greater size, the former being almost twice as large as the latter. In the upper jaw, the middle are distinguished from the lateral incisors, also, by their well-marked su- ' [It maybe well to observe, that the illustrations are all taken from teeth of the upper jaw, in which the general characters of each class are more strongly marked than in those of the lower.]](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21196801_0203.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)