Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The anatomy of the human body / By J. Cruveilhier. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the University of Massachusetts Medical School, Lamar Soutter Library, through the Medical Heritage Library. The original may be consulted at the Lamar Soutter Library at the University of Massachusetts Medical School.

249/944 (page 225)

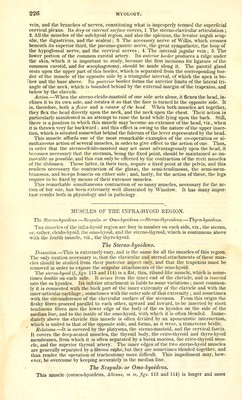

![vening cellular tissue is always adipose, and capable of containing a large quantity of fat, as we find in individuals who have what is called a double chin. There are no lym- phatic glands between this muscle and the skin ; they are all situated beneath the mus- cle. The relations of the deep surface of the platysma are very numerous. It covers the supra and sub-hyoid, and the supra-clavicular regions, being separated from all the structures beneath it by the cervical fascia, to which it is united by loose cellular tissue, seldom containing any fat. If we examine these relations in detail, we find, proceeding from below upward, that it covers, 1. The clavicle, the pectoralis major, and the deltoid ; 2. In the neck, the external jugular vein, and also the anterior jugulars where they ex- ist, the superficial cervical plexus, the sterno-mastoid, the omo-hyoid, the sterno or cle- ido hyoid, the digrastic, and the mylo-hyoid muscles, the sub-maxillary gland, and the IjTTiphatic glands at the base of the jaw. In front of the sterno-mastoid, it covers the common carotid artery, the internal jugular vein, and the pneumogastric nerve ; behind the sterno-mastoid, it covers the scaleni muscles, the nerves of the brachial plexus, and some of the lower nerves of the cervical plexus. 3. In the face, it covers the external maxillary or facial artery, the masseter and buccinator muscles, the parotid gland, &c. Action.—The platysma is the most distinctly marked vestige in the human body of the panniculps carnosus of animals ; and it can produce slight wrinkles in the skin of the neck. Its anterior border, especially at its insertion near the symphysis menti, is the thickest part of the muscle, and therefore projects slightly during its contraction. It is one of the depressors of the lower jaw ; it also depresses the lower lip, and, slightly, the commissure of the lips. It therefore assists in the expression of melancholy feehngs, but it is antagonized by the accessory portion, which draws the angle of the lips upward and a little outward, and thus concurs in the expression of pleasurable emotions ; hence its name, risonus. The Sterno-deido-mastoideus. Dissection.—Divide the skin and the platysma from the mastoid process to the top of the sternum, in an oblique line, running downward and forward; reflect the two flaps, one forward and the other backward, taking care to remove at the same time the strong fascia which covers the muscle. In order to obtain a good view of the superior attach- ments, make a horizontal incision along the superior semicircular line of the occipital bone.. The stcrno-clcido-mastoid {b,fig. 113) occupies the anterior and lateral regions of the neck. It is a thick muscle, bifid below, and narrower in the middle than at either end. It arises, by two very distinct masses, from the inner end of the clavicle, and from the top of the sternum in front of the fourchette, and is inserted into the mastoid process and the superior semicircular line of the occipital bone. The sterna] origin consists of a tendon prolonged for a considerable distance in front of the fleshy fibres. The clavic- Fig. 11 J. ular origin consists of very distinct parallel ten- dinous fibres, attached to the inner side of the anterior edge and upper surface of the clavicle, to a very variable extent, an important fact in surgical anatomy. There is often a considerable cellular interval between these two origins; sometimes this interval scarcely exists, but, in all cases, the two portions of the muscle can be readily separated. From this double origin the fleshy fibres proceed, forming two large bundles, which remain distinct for some time. Many anatomists, therefore, Albinus in particular, have considered it as consisting of two separate mus- cles, which they describe as the sterno-mastoid and the cleido-mastoid; a division that is sanc- tioned by the comparative anatomy of this mus- cle. The sternal portion of the muscle is the larger, and passes upward and outward ; the cla- vicular portion proceeds almost vertically upward, behind the other, and is entirely concealed by it at the middle of the neck; the two portions still remain separate, although approximated; ulti- mately they become united, and are inserted into the apex and anterior surface of the mastoid pro- cess by a very strong tendon, which runs for some distance along the anterior border of the muscle, and also into the two external thirds of the superior semicircular line of the occipital bone, by a thin aponeurosis. The direction or axis of the sterno-mastoid passes obliquely upward, backward, and outward. The relations of this muscle are very important. Its superficial or external surface is covered by the skin and platysma, from which it is. separated by the external jugular](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21196801_0249.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)