On the microscopic pathology of cancer, (with a woodcut) / by John Houston, M.D.

- John Houston

- Date:

- 1844

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: On the microscopic pathology of cancer, (with a woodcut) / by John Houston, M.D. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by The University of Glasgow Library. The original may be consulted at The University of Glasgow Library.

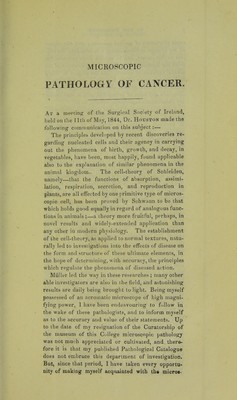

6/20 (page 4)

![copic characters of morbid growths ; and the object of my present communication is to introduce the sub- ject to this society, and to exhibit some preparations from the museum which I regard as illustrative of the several varieties of cancer. As the subject is likely to be new to some of my hearers, I think it right to make a few such general observations regarding the structure and form of primordial cells as may render' my observations intelligible, equally, to all. A cell is the ultimate limit of organised structure— an atom, beyond which, subdivision is impracticable. It abruptly assigns the confines of microscopic analysis. The diversities of size in these primitive cells range from dimensions of immeasurable minute- ness to the magnitude of a cell visible to the naked eye; from the l-376.000th to the l-20th part of an inch. And a definite scale is assigned to the primary organic cell proper to various structures. The typical elements of a primordial cell are three. First, an external sac or cell-membrane; then a smaller vesicle or nucleus; and thirdly, a smaller still, the nucleolus, [See diagragm, fig. I.] By the significant assistance of three small con- centric lines, it is thus practicable definitively to ex- press the profound truth, that a slender tripartite cellule is typical of the common germ from which all animal and vegetable existence proceeds. It is the universal focus of parentage to every individual within the confines of organic nature.—Dr. Williams. Primary cells propagate themselves by the produc- tion of cells similar to themselves. When they have attained a certain stage in their existence the cells usually burst, by an act to which the term dehiscence is applied, and shed forth their nuclei, which, by the imbibition of nutriment from surrounding appropri- ate material, grow and multiply like their parents. In its pathological relations this is a very important • circumstance. For when the malignant tendency, that of cancer for example, has been once established in a part by the organisation of a cancerous primary cell, in virtue of this extraordinary power, which, from the beginning, inheres in the cell of multiplying its kind, the continuance of the diseased process in the part is certain and inevitable. The whole frame- work of the body being thus composed of ultimate](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21476007_0006.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)