Report of the Director-General of Public Health, New South Wales.

- New South Wales. Department of Public Health

- Date:

- [1926]

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Report of the Director-General of Public Health, New South Wales. Source: Wellcome Collection.

211/212 page 169

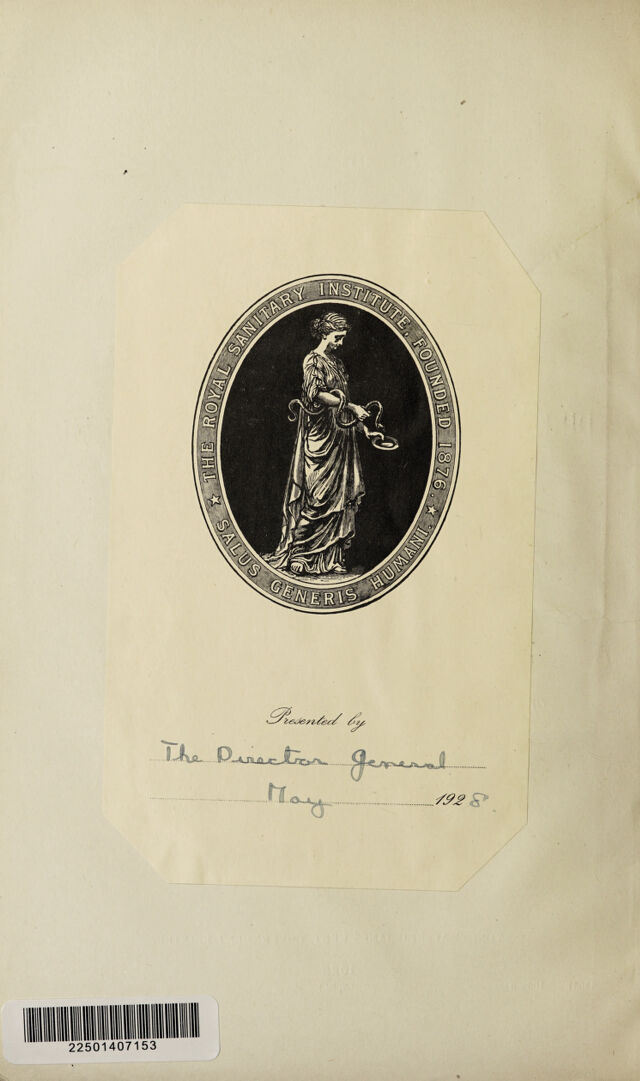

![Pathology.—Clunies Ross lias brought forward evidence which strongly suggests that the poison has a specific affinity for the motor cells of the spinal cord and cranial nerve nuclei, producing in them more or less complete abrogation of function without noteworthy morphological changes. The autonomic nervous system appears to be somewhat hyper-irritable, as shown by the dilation of the pupil, the vomiting and the purging seen in various cases. As would be expected from the transitory nature of the paralyses in those cases that recover, no gross disorganisation, or even clearly defined lesions, are found in the central nervous system. Sections of the cord and brain show some engorgement of the vessels and more or less round cell infiltration of the tissues. Numbers of new capillaries may be formed and numerous minute haemorrhages were observed in the case studied by Ferguson (1924). No change can be made out in the nerve cells beyond an inconstsnt slight alteration of their staining properties. The cortex was unaffected in the experimental cases. No definite changes are to be found in other organs except pulmonary congestion due to the respiratory embarrassment. There is, of course, some inflammatory reaction at the site of attachment of the tick, but the extent of this has no relation to the disease. Clinical Features.—The “ incubation period ” is five days or more after the attachment of the tick. Frequently the first symptom noticed is anorexia, the patient, though apparently in good health, refusing a meal. At the same time, or within a few hours, some unsteadiness in walking and inco-ordination of leg movements is observed. By the next day there is complete flaccid paralysis of the lower limbs with abolition of the reflexes. By the third day the arms show great weakness, and inco-ordination, and respiration becomes laboured, all the accessory muscles being brought into play, though weakly. The pupil is usually dilated, and may not react; the corneal reflex may be modified or abolished. Vomiting and purging may occur. The muscles of deglutition and speech may show paresis. In some cases there is initial mental irritability progressing to delirium and coma. A rise of temperature is frequently seen at some stage in the disease. Death is, in many cases at least, due to respiratory paralysis, the heart beating strongly to the end. There is considerable variation in the intensity of the symptoms, some cases showing little more than a transitory paresis with inco-ordination of the lower limbs, with, perhaps, some dilation of the pupil or some vomiting or fever. Speaking generally, it appears that the younger the patient the more severe are the symptoms. This greater susceptibility of the young is possibly a function of the relation of body weight to the amount of toxin injected. There is also a good deal of variation in the predominating symptoms in different cases. In the case reported by St. Leger Moss (1924), for example, the eye symptoms were the most striking feature, little else being complained of beyond some weakness and pain in the legs. The cerebral symptoms, too, are inconstant, being well marked in some cases and apparently absent in others; they are apparently slight or absent in any but severe cases, a statement which applies also to the respiratory embarrassment. The most definite and constant feature of all cases is the interference with the muscular activity of the lower limbs, which may or may not progress to complete paralysis. Death usually occurs on the fourth or fifth day, but may be later. In non-fatal cases the symptoms begin to abate about the same time, and in a few days the patient is perfectly well, and shows no sign of the really serious illness through which he has passed. Diagnosis.—The sudden onset may suggest acute anterior poliomyelitis, and the twro diseases have a number of features in common. The diagnosis depends on the recovery of the tick and the rapid progress to complete recovery in non-fatal cases of tick paralysis. The paralyses and motor disturbances have a much more extensive distribution in severe cases of tick paralysis than is usual in poliomyelitis. Hysterical paralyses may have to be excluded. Prognosis.—It is not possible to obtain an accurate estimate of the mortality from the few cases hitherto recorded, but it appears to be fairly high. The prospect of recovery increases in general with the age of the patient. Respiratory or cerebral symptoms arc of grave significance. The earlier the tick us discovered and removed the better is the outlook, though removal is not necessarily followed by arrest of the disease. Treatment.—In suspected cases the whole body should be carefully searched for ticks, and all founel shoulel be removed at once. It is unwise to rest content with fineling one tick—there may be others present which are causing the symptoms. It is sufficient to remove the bedy of the tick, leaving the rostrum embeeleleel (it docs no great harm), but it is better to dissect out the whole tick. Local treatment after removal of the tick does not appear to influence the disease. The patient should be kept in bed on light diet and with plenty of fluid, if it can be taken. Elimin¬ ative treatment by the bowel, kidney, and skin may be tried, but should not be pushed so far as to reduce tin patient’s strength. The only treatment known which will affect the course of the disease is removal of the tick, and that is not always effective. References. Backhouse, J., 1843. A Narrative of a Visit to the Australian Colonies, p. 187. Bancroft, J., 1884. Queensland Ticks and Tick Blindness. Aus. Med. Gaz., iv., 37. Cleland, J. B. 1912. Injuries and Diseases of Man in Australia Attributable to Animals (except insects). Aus. Med. Gaz., xxxii, 295-299. Dodd, S., 1921. Tick Paralysis. Jl. Comp. Path., and Therap., xxxiv, 309-323. Eaton, R. M., 1913. A Case of Tick Paralysis followed by a Widespread Transitory Muscular Paralysis. Aus. Med. Gaz., xxxiii, 391-394. Ferguson, E. W., 1923. Australian Ticks. Report Dir. Gen. Public Health, N.S.W., 1923, 147-157. . 1924. Deaths from Tick Paralysis in Human Beings.' Med Jl. Aus., ii, 11th Year, 340-348. Fielding, J. W., 1926. Australian Ticks. C‘wlth, Aus. Serv. Publn. (Trop. Div.), No. 9, 114 pp. Hovell, 1824. Diary of a Journey to Port Phillip, 1824-1825. Roy. Aust. Hist. Soc., vii, pt. 6, 358 (1921). Moss, H. St. Leger, i924. A Case of Tick Paralysis. Med. Jl. Aus., ii, 11th Year, 556. Ross, I. Clunies, 1924. The Bionomics of Ixodes hotocyclus Neuman, with a redescription of the adult and nymphal stages and a description of the larvae. Parasitology, xvi, 365-381. .. 1926. An Experimental Study of Tick Paralysis in Australia. Parasitology, xviii, 410-429. [16 Graphs and 1 Map.] Sydney: Ored James Kent, Government Printer—1028.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b31485170_0211.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)