A practical treatise on fractures and dislocations / by Frank Hastings Hamilton.

- Frank Hastings Hamilton

- Date:

- 1891

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: A practical treatise on fractures and dislocations / by Frank Hastings Hamilton. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, through the Medical Heritage Library. The original may be consulted at the Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, Harvard Medical School.

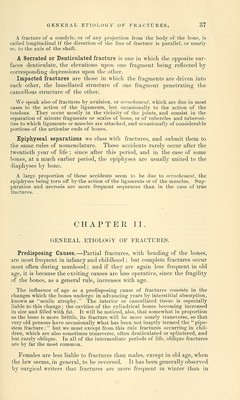

32/858 page 38

![summer, and an explanation has been sought for in the greater rigidity of the muscles during the cold weather, and the greater liability to falls upon the ice and frozen ground. It is a question whether fractures are actually more frequent in the winter than in the summer. If, on the one hand, the rigidity of the muscles and falls upon slippery walks are active causes in the production of fractures in the one season ; on the other hand, falls from buildings and accidents from a great variety of similar causes are equally active agents in the other. Mollifies ossium, rickets, cancer, tertiary lues, scrofula, gout, scurvy, mercurialization, and, in short, all diseases dependent upon cachexise, are believed more or less to predispose to the occurrence of fractures. [Gurlt thinks, however, there is no evidence that scrofula or gout predisposes to fracture, and that syphilis is not a very frequent cause.] Inflammation of the periosteum also, or of the bone itself, may pre- dispose to fracture. It is said, moreover, that the bones of persons who have lain a long time in bed break easily. The liability to fracture is also sometimes hereditary, when there exists no recognized cachexia. [Goddard knew a boy who had fourteen fractures; his mother had six frac- tures ; his brother had thirteen fractures.] We may suppose that the proportion of the earthy salts in the bones is increased. Trophic changes consequent upon disease of the nerve-centres may give rise to a fragility of the bones. It has been observed in lunatics, the paralytic, and in persons affected with locomotor ataxia.1 Remarkable examples of fragility of the bones have been from time to time recorded. Gibson relates the case of a man who, at the age of nineteen, had suffered twenty-four fractures. Arnott speaks of a girl who, at the age of fourteen, had suffered thirty-one fractures. Esquirol had in his possession the skeleton of a woman in which were found traces of more than two hundred fractures. And we have had, at the Charity Hospital, a man aged fifty-three, who had suffered eleven fracture s and two dislocations, in whose case the sus- ceptibility both to fractures and to dislocations appeared to be hereditary.2 In most of these cases, so far as is known, union occurred rapidly. Exciting Causes.—The exciting, determining, or immediate causes of fractures are of two kinds : mechanical violence and muscular action. Of these two, mechanical or external violence is much the more frequent cause; and this violence may operate in two ways: by acting directly upon the bone at the point at which it separates, and then we say the fracture is direct, or from direct violence; or by acting upon some point remote from the seat of fracture, and then we say the fracture is indirect, or from a counter-stroke. When a person falls from a height, alighting upon his feet, and the leg or thigh is broken, the fracture is indirect; so also if the bone is broken by flexion or torsion. Even direct pressure upon one side of a long bone in a child may produce a partial fracture upon the opposite side, which is properly an indirect fracture; or a direct blow upon the trochanter major may occasion a counter- fracture through the neck of the femur. i Weir Mitchell, Amer. Journ. Med. Sci., July, 1873, p. 113. 2 The Physician and Pharmaceutist, Feb. ]870. Report by Armenag Assadoorian.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21056699_0032.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)