The history of Clerkenwell / by William J. Pinks ; with additions by the editor, Edward J. Wood.

- Pinks, William J. (William John), 1829-1860

- Date:

- 1881

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: The history of Clerkenwell / by William J. Pinks ; with additions by the editor, Edward J. Wood. Source: Wellcome Collection.

38/886 (page 8)

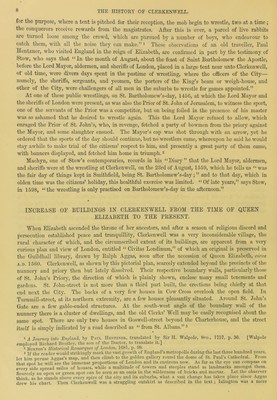

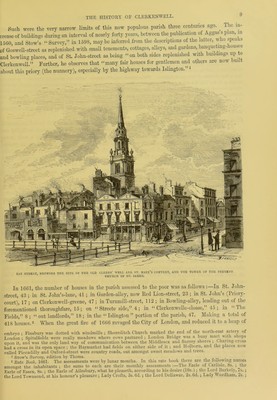

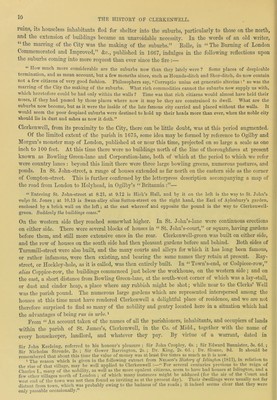

![for the purpose, where a tent is pitched for their reception, the mob begin to wrestle, two at a time ; the conquerors receive rewards from the magistrates. After this is over, a parcel of live rabbits arc turned loose among the crowd, which are pursued by a number of boys, who endeavour to catch them, with all the noise they can make.” 1 These observations of an old traveller, Paul Hentzncr, who visited England in the reign of Elizabeth, are confirmed in part by the testimony of Stow, who says that “In the month of August, about the feast of Saint Bartholomew the Apostle, before the Lord Mayor, aldermen, and sheriffs of London, placed in a large tent near unto Clerkenwcll, of old time, were divers days spent in the pastime of wrestling, where the officers of the City— namely, the sheriffs, sergeants, and yeomen, the porters of the King’s beam or weigh-house, and other of the City, were challengers of all men in the suburbs to wrestle for games appointed.” At one of these public wrestlings, on St. Bartholomew’s-day, 1456, at which the Lord Mayor and the sheriffs of London were present, as was also the Prior of St. John of Jerusalem, to witness the sport, one of the servants of the Prior was a competitor, but on being foiled in the presence of his master was so ashamed that lie desired to wrestle again. This the Lord Mayor refused to allow, which enraged the Prior of St. John’s, who, in revenge, fetched a party of bowmen from the priory against the Mayor, and some slaughter ensued. The Mayor’s cap was shot through with an arrow, yet lie ordered that the sports of the day should continue, but no wrestlers came, whereupon he said he would stay awhile to make trial of the citizens’ respect to him, and presently a great party of them came, with banners displayed, and fetched him home in triumph.2 Machyn, one of Stow’s contemporaries, records in his “Diary” that the Lord Mayor, aldermen, and sheriffs were at the wrestling at Clerkenwcll, on the 23rd of August, 1559, which he tells us “ was the fair day of things kept in Smithfield, being St. Bartholomew’s-day; ” and to that day, which in olden time was the citizens’ holiday, this healthful exercise was limited. “ Of late years,” says Stow, in 1598, “the wrestling is only practised on Bartholomew’s-day in the afternoon.” INCREASE OF BUILDINGS IN CLERKENWELL FROM THE TIME OF QUEEN ELIZABETH TO THE PRESENT. When Elizabeth ascended the throne of her ancestors, and after a season of religious discord and persecution established peace and tranquillity, Clerkenwcll was a very inconsiderable village, the rural character of which, and the circumscribed extent of its buildings, are apparent from a very curious plan and view of London, entitled “ Civitas Londinum,” of which an original is preserved in the Guildhall library, drawn by Ralph Aggas, soon after the accession of Queen Elizabeth, circa a.i). 1560. Clerkenwell, as shown by this pictorial plan, scarcely extended beyond the precincts of the nunnery and priory then but lately dissolved. Their respective boundary walls, particularly those of St. John’s Priory, the direction of which is plainly shown, enclose many small tenements and gardens. St. Jolin-street is not more than a third part built, the erections being cliiefly at that end next the City. The backs of a very few houses in Cow Cross overlook the open field. In Turnmill-strcet, at its northern extremity, arc a few houses pleasantly situated. Around St. John’s Gate are a few gable-ended structures. At the south-west angle of the boundary wall of the nunnery there is a cluster of dwellings, and the old Clerks’ Well may be easily recognised about the same spot. There are only two houses in Goswell-strcet beyond the Charterhouse, and the street itself is simply indicated by a road described as “ from St. Albans.” 3 1 A Journey into England, by Paul Hentzner, translated by Sir H. Walpole, 8vo., 1757, p. 3G. [Walpole employed Richard Rcntley, the soil ot the Doctor, to tianslate it.] 2 Burton’s Historical Itonargucs of London, 16bl, p. 98. 3 If the reader would strikingly mark the vast growth of England’s metropolis during the last three hundred years, let him peruse Aggas’s map, and then climb to the golden gallery round the dome of St. Paul’s Cathedral. From that spot he will see the immense proportions of London and its environs now. As far as the eye can compass on every side spread miles of houses, while a multitude of towers and steeples stand as landmarks amongst them. Scarcely an open or green spot can be seen as au oasis in the wilderness of bricks and mortar. Let the observer think, as he stands above every spire of the city and its suburbs, what a vast change has taken place since Aggas drew 'his chart. Then Clerkenwell was a straggling outskirt as described in the text ; Islington was a mere](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b24863944_0038.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)