Volume 1

Long-range program and research needs in aging and related fields : hearings before the Special Committee on Aging, United States Senate, Ninetieth Congress, first session Washington, D.C. December 5 and 6, 1967.

- United States Senate Special Committee on Aging

- Date:

- 1968-

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Long-range program and research needs in aging and related fields : hearings before the Special Committee on Aging, United States Senate, Ninetieth Congress, first session Washington, D.C. December 5 and 6, 1967. Source: Wellcome Collection.

462/500 (page 452)

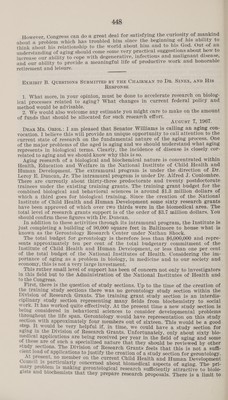

![2 A former FAA staff member says the data was at the initial analysis stage when the project was terminated. It is not clear how much statistical disarrary existed. Different sources give different estimates. Dr. Wentz says, “termina- tion of the project was not made on scientific grounds.” Turning to the Lovelace project, the House committee referred to “known statistical weaknesses.” It said the NIH study section reviewing Lovelace pro- posals in 1961 “expressed concern about the lack of any plan for statistical analysis of the data to be gathered and the inclusion of too many variables for an aging study. It warned that unless the data gathered conformed to analytical objectives, the entire project could prove worthless. Nevertheless, the study sec- tion recommended and the NIH approved a three-year grant, unaccompanied by any requirement of the grantee to eliminate project deficiencies to qualify for second- and third-year funds.” The House committee noted that NIH approved a five-year extension of the grant in 1964, though little actual analysis had been undertaken then. Lovelace reported in August 1966 that data analysis was proceeding. Basic needs.—A gerontologist said he was “shaken by the lack of any compre- hension by the committee of the basic needs of scientific methods. What they call duplication is replication,” he said, meaning the use of different measures in the same domain rather than repetition of the same measures. The same gerontologist thought some aspects of the FAA project were scientifically sound but others questionable. “The publish-or-perish system of rewards in science,” ran an oft-heard com- ment, “discourages long-term research, which has few early payoffs to boost a man’s career and salary status. In ‘a government in-house study, it is hard to get and keep board-certified specialist-physicians at Civil Service pay scales, which. rarely exceed $20,000 a year.” Neglect of aging research.—In view of such difficulties, said one observer, it was “astonishing” that GCRI held its personnel together for five years. ‘“Because aging is by far the most scandalously neglected area of medical research,” he added, “the death of this project—saving 0.02% of all federal spending on medical research—does not strike me as a masterpiece of good management. Aging is the last area in which you want to look a gift horse in the mouth.” According to the report, federal support of aging research in 1966 was an esti- mated $12.8 million, including $4.5 million through NIH. The report lists 8 “major long-term medical research studies of aging in humans, sponsored by six federal agencies, fiscal year 1966,” counting GCRI and Lovelace. Total estimated spending for the 8 studies : $1.2 million. One gerontologist questioned the list. He noted its inclusion of 3 Defense De- partment studies dealing with physiological changes in pilots. the Atomic Energy Commission’s study of Hiroshima, and Nagasaki survivors of the atomic bomb- ings. These were questioned as not being true aging projects. What remains of the list are [1] a study of 600 aging male volunteers of all occupations, being carried out at Baltimore City Hospitals by NIH’s Gerontology Branch under Dr. Nathan Shock and [2] a Veterans Administration study in Boston of “Normative Aging” in 900 male veterans aged 25 to 100. A physician in gerontology pointed to a need for directed research in longi- tudinal studies. “These studies cannot be arranged for the asking. When you deal with research on arthritis, for example, the scientific panels at NIH who select projects for grants don’t pick only 1 out of 25 for support. They may pick Zor3 which are pretty much alike because overlap and confirmation of results are desired. It’s relatively cheap. The grants may be $25,000 and the work can be completed by one investigator in a year.” The longitudinal ball game.—‘“In longitudinal studies, you’re talking about something far more complex. It’s a different ball game; the same rules cannot apply, because the investment of money and talent is of a new order of magnitude. You have to put your eggs in fewer baskets. You have to combine study proposals, using your best scientific judgement. So, the House committee has a point in Saying that we ought to look at longitudinal research from a central viewpoint. But this is quite a departure from the way most researchers are accustomed to Wore, and it may not be fair to criticize FAA and NIH without noting this. me og ese: Same os recognize the new ball game, you have to do it in Con- SS, TOO. ust assure long-term support, and in this regard you run into problems stemming from the fact that Congress prefers to make annual budget reviews and resists long commitments.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b32178128_0001_0462.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)