A treatise on the diseases of the eye / by W. Lawrence.

- Sir William Lawrence, 1st Baronet

- Date:

- 1854

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: A treatise on the diseases of the eye / by W. Lawrence. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, through the Medical Heritage Library. The original may be consulted at the Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, Harvard Medical School.

53/996 (page 43)

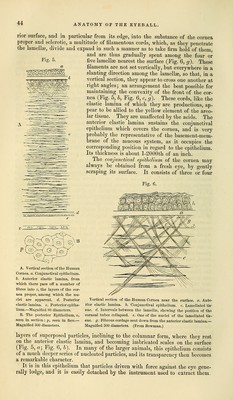

![Pressure on the globe, in the dead state, renders the cornea opaque, more or less completely, according to the degree of force employed; when the pressure is remitted, it again becomes transparent. It has not been ascertained whether a similar effect may be produced by ana- logous causes in the living eye; for example, whether the general tension pro- duced by increase of the contents of the globe, may render the cornea opaque. Mr. Wardrop supposed that this would happen, and hence advised the plan of evacuating the aqueous humour, to diminish tension. In thickness, the cornea is equal to the thickest portion of the sclerotica. In resistance to the knife it may be compared to parts of cartilaginous structure ; it is so firm, that we are obliged to use some force in penetrating it with a knife or needle. When we first operate on the eye, we find much greater resistance to the entry of an instrument than the transparency of the membrane would have led us to anticipate. The fibrous structure, and the loose connection of the parts, lead to another risk, namely, that of the point of an instrument pass- ing between, instead of going completely through them. The density and com- pactness of the cornea, the resistance which it consequently offers, and its being composed of parts in some degree loosely connected, are circumstances which should be constantly borne in mind in operating on this membrane. The cornea in the human eye forms a pretty regular portion of a sphere, and is of equal thickness [about one-thirtieth of an inch] at the circumference and in the centre; it is consequently convex on its external or anterior surface, and concave on its posterior surface. Although it appears like a homogeneous membrane, we consider it to be made up of three different structures. The anterior surface is a mucous membrane, being a continuation of the conjunctiva; [4', Fig. 1], the great bulk of the part is made up of the fibrous, or fibro-cartila- ginous structure already described, and usually called the corneal laminae, [4, Fig. 1] ; the internal surface is a firm, cartilaginous, perfectly transparent mem- brane, adhering closely to the proper corneal substance, and called membrane of the aqueous humou?-1 [6, Fig. 1], being supposed to secrete, or to have a share in secreting that fluid. Dr. Jacob2 observes, that this membrane preserves its transparency after maceration, or immersion in hot water, acid, or spirit, all which render the corneal lamina opaque ; and that it separates from the latter when the cornea is immersed in any fluid capable of corrugating it, after which it can easily be detached, and exhibited in a distinct state. He adds, that it passes under the sclerotic for a short distance between it and the ciliary liga- ment, and terminates with a defined edge. According to this representation, the cornea consists of three different structures; the anterior or mucous layer, the fibro-cartilaginous substance in the middle, and the membrane of the aque- ous humour lining the internal or posterior surface. These, and especially the first two, are most firmly united, we might say consolidated, into one apparently uniform transparent structure. [The microscopical researches of Todd and Bowman (Physiological Anatomy) have shown that the cornea is composed of five coats or layers. These are, from before backwards, the conjunctival layer of epithelium, the anterior elastic lamina, the cornea proper, the posterior elastic lamina, and the epithelium of the aqueous humour, ov posterior epithelium. (Fig. 5.) The anterior elastic lamina is transparent, homogeneous, coextensive with the front of the cornea, and forms the anterior boundary of the cornea proper. It is a peculiar tissue, the office of which seems to be that of maintaining the exact curvature of the front of the cornea; for there pass from all parts of its poste- i It was first noticed by Descemet, ami i.s .sometimes named after him.—Observations stir In Choroids, in the Mem. pnsi'it/es a 1'Arad. den. Sci. torn. v. 1759, 1 Medico-Chir. Trans. yoI. xii. p. 5U3.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21063539_0053.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)