A treatise on the diseases of the eye / by W. Lawrence.

- Sir William Lawrence, 1st Baronet

- Date:

- 1854

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: A treatise on the diseases of the eye / by W. Lawrence. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, through the Medical Heritage Library. The original may be consulted at the Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, Harvard Medical School.

60/996 (page 50)

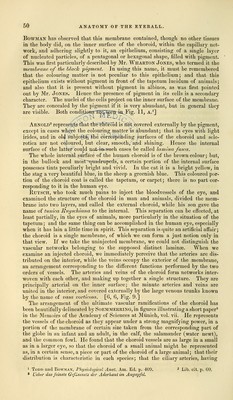

![Bowman has observed that this membrane contained, though no other tissues in the body did, on the inner surface of the choroid, within the capillary net- work, and adhering slightly to it, an epithelium, consisting of a single layer of nucleated particles, of a pentagonal or hexagonal shape, filled with pigment. This was first particularly described by Mr. Wharton Jones, who termed it the membrane of the black pigment. In using this name, it must be remembered that the colouring matter is not peculiar to this epithelium; and that this epithelium exists without pigment in front of the tapetum lucidum of animals; and also that it is present without pigment in albinos, as was first pointed out by Mr. Jones. Hence the presence of pigment in its cells is a secondary character. The nuclei of the cells project on the inner surface of the membrane. They are concealed by the pigment if it is very abundant, but in general they are visible. Both conditionsaTJeTSeeri in. Fig. 11, A.1] y^cQP^ ^ X, Arnold3 represents that the choroid is ridt covered externally by the pigment, except in cases where the colouring matter is abundant; that in eyes with light irides, and in old subject^ the corresponding Surfaces of the choroid and scle- rotica are not coloured, but clear, smooth,'and shining. Hence the internal surface of the latter could not-incsuch cases be called lamina fusca. The whole internal surface of the human choroid is of the brown colour; but, in the bullock and most^uadrupeds, a certain portion of the internal surface possesses tints peculiarly bright and vivid. In the cat it is a bright yellow, in the stag a very beautiful blue, in the sheep a greenish blue. This coloured por- tion of the choroid coat is called the tapetum, or carpet; there is no part cor- responding to it in the human eye. Ruysch, who took much pains to inject the bloodvessels of the eye, and examined the structure of the choroid in man and animals, divided the mem- brane into two layers, and called the external choroid, while his son gave the name of tunica Ruyschiana to the internal. This separation can be effected, at least partially, in the eyes of animals, more particularly in the situation of the tapetum; and the same thing can be accomplished in the human eye, especially when it has lain a little time in spirit. This separation is quite an artificial affair; the choroid is a single membrane, of which we can form a just notion only in that view. If we take the uninjected membrane, we could not distinguish the vascular networks belonging to the supposed distinct laminae. When we examine an injected choroid, we immediately perceive that the artei'ies are dis- tributed on the interior, while the veins occupy the exterior of the membrane, an arrangement corresponding to the different functions performed by the two orders of vessels. The arteries and veins of the choroid form networks inter- woven with each other, and making up together a single structure. They are principally arterial on the inner surface; the minute arteries and veins are united in the interior, and covered externally by the large venous trunks known by the name of vasa vorticosa. [6, 6, Fig. 9.] The arrangement of the ultimate vascular ramifications of the choroid has been beautifully delineated by Soemmerring, in figures illustrating a short paper3 in the Memoirs of the Academy of Sciences at Munich, vol. vii. He represents the vessels of the choroid as they appear under a strong magnifying power, in a portion of the membrane of certain size taken from the corresponding part of the globe in an infant and an adult, in the calf, the salamander (water newt), and the common fowl. He found that the choroid vessels are as large in a small as in a larger eye, so that the choroid of a small animal might be represented as, in a certain sense, a piece or part of the choroid of a large animal; that their distribution is characteristic in each species; that the ciliary arteries, having 1 Todd and Bowman, Physiological Anat. Am. Ed. p. 409. 2 Lib. cit. p. 60. 3 Uebtr dasfeinste Gefiissnete der Aderhaul im Augapfel.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21063539_0060.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)