A treatise on the diseases of the eye / by W. Lawrence.

- Sir William Lawrence, 1st Baronet

- Date:

- 1854

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: A treatise on the diseases of the eye / by W. Lawrence. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, through the Medical Heritage Library. The original may be consulted at the Francis A. Countway Library of Medicine, Harvard Medical School.

64/996 (page 54)

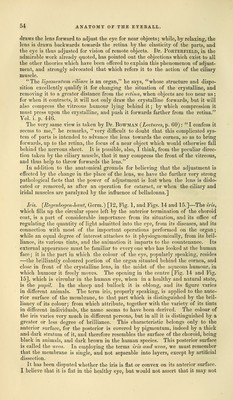

![draws the lens forward to adjust the eye for near objects; while, by relaxing, the lens is drawn backwards towards the retina by the elasticity of the parts, and the eye is thus adjusted for vision of remote objects. Dr. Porterfield, in the admirable work already quoted, has pointed out the objections which exist to all the other theories which have been offered to explain this phenomenon of adjust- ment, and strongly advocated that which refers it to the action of the ciliary muscle. The ligamentum ciliare is an organ, he says, whose structure and dispo- sition excellently qualify it for changing the situation of the crystalline, and removing it to a greater distance from the retina, when objects are too near us; for when it contracts, it will not only draw the crystalline forwards, but it will also compress the vitreous humour lying behind it; by which compression it must press upon the crystalline, and push it forwards farther from the retina. Vol. i. p. 446. The very same view is taken by Dr. Bowman {Lectures, p. 60): I confess it seems to me, he remarks, very difficult to doubt that this complicated sys- tem of parts is intended to advance the lens towards the cornea, so as to bring forwards, up to the retina, the focus of a near object which would otherwise fall behind the nervous sheet. It is possible, also, I think, from the peculiar direc- tion taken by the ciliary muscle, that it may compress the front of the vitreous, and thus help to throw forwards the lens. In addition to the anatomical grounds for believing that the adjustment is effected by the change in the place of the lens, we have the further very strong pathological facts that the power of adjustment is lost when the lens is dislo- cated or removed, as after an operation for cataract, or when the ciliary and iridal muscles are paralyzed by the influence of belladonna.] Iris. (Regenbogen-haut, Germ.) [12, Fig. 1, and Figs. 14 and 15.]—The iris, which fills up the circular space left by the anterior termination of the choroid coat, is a part of considerable importance from its situation, and its office of regulating the quantity of light admitted into the eye, from its diseases, and its connection with most of the important operations performed on the organ; while an equal degree of interest attaches to it physiognomically, from its bril- liance, its various tints, and the animation it imparts to the countenance. Its external appearance must be familiar to every one who has looked at the human face; it is the part in which the colour of the eye, popularly speaking, resides —the brilliantly coloured portion of the organ situated behind the cornea, and close in front of the crystalline lens, in the midst of the aqueous humour, in which humour it freely moves. The opening in the centre [Fig. 14 and Fig. 15], which is circular in the human eye, when in a healthy and natural state, is the pupil. In the sheep and bullock it is oblong, and its figure varies in different animals. The term iris, properly speaking, is applied to the ante- rior surface of the membrane, to that part which is distinguished by the bril- liancy of its colour; from which attribute, together with the variety of its tints in different individuals, the name seems to have been derived. The colour of the iris varies very much in different persons, but in all it is distinguished by a greater or less degree of brilliance. This characteristic belongs only to the anterior surface, for the posterior is covered by pigmentum, indeed by a thick and dark stratum of it, and therefore resembles the surface of the choroid, being black in animals, and dark brown in the human species. This posterior surface is called the uvea. In employing the terms iris and uvea, we must remember that the membrane is single, and not separable into layers, except by artificial dissection. It has been disputed whether the iris is flat or convex on its anterior surface. I believe that it is flat in the healthy eye, but would not assert that it may not](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21063539_0064.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)