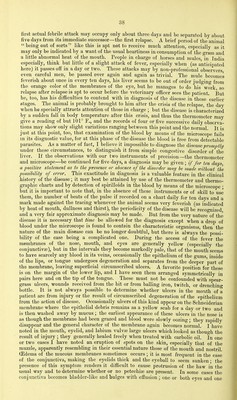

Report of veterinary surgeon J. H. Steel, A. V. D., on his investigation into an obscure and fatal disease among transport mules in British Burma, which he found to be a fever of relapsing type, and probably identical with the disorder first described by Dr. Griffith Evans under the name "Surra", in a report (herewith reprinted) published by the Punjab Government, Military Department, No. 439-4467, of 3rd. December 1880-vide the Veterinary Journal (London), 1881-1882 / [By Steel, J. H.].

- Steel, John Henry

- Date:

- 1886

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Report of veterinary surgeon J. H. Steel, A. V. D., on his investigation into an obscure and fatal disease among transport mules in British Burma, which he found to be a fever of relapsing type, and probably identical with the disorder first described by Dr. Griffith Evans under the name "Surra", in a report (herewith reprinted) published by the Punjab Government, Military Department, No. 439-4467, of 3rd. December 1880-vide the Veterinary Journal (London), 1881-1882 / [By Steel, J. H.]. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by Royal College of Physicians, London. The original may be consulted at Royal College of Physicians, London.

62/92 page 38

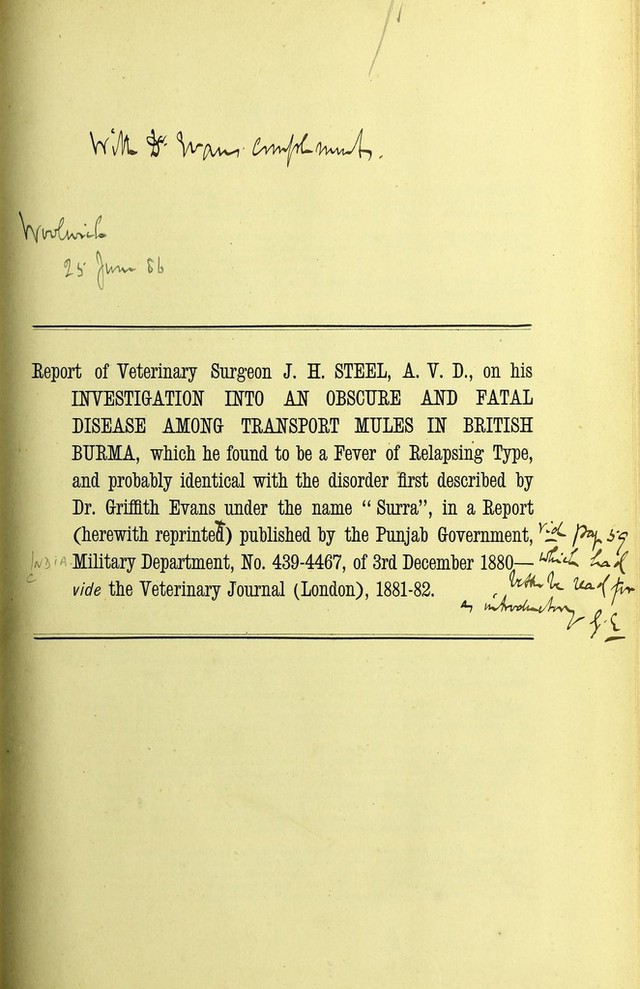

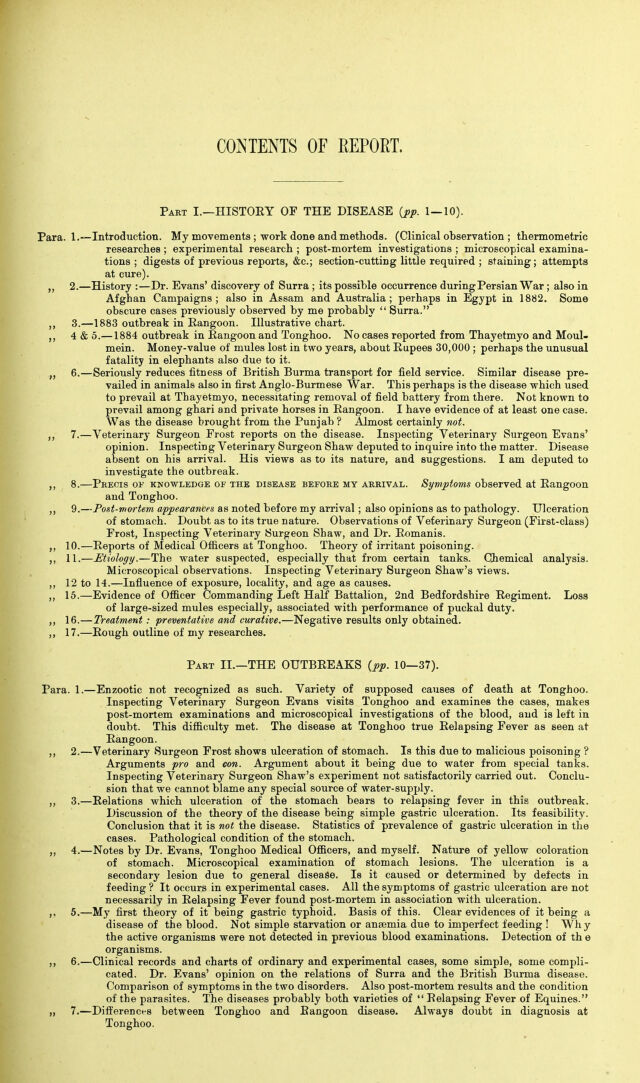

![first actual febrile attack may occupy only about three days and be separated by about five days from its immediate successor—the first relapse. A brief period of the animal beiDg out of sorts like this is apt not to receive much attention, especially as it may only be indicated by a want of the usual heartiness in consumption of the o-ram and a little abnormal heat of the mouth. People in charge of horses and mules in India especially, think but little of a slight attack of fever, especially when (as anticipated here) it passes off in a day or two. These attacks may by non-professional observers even careful men, be passed over again and again as trivial. The mule becomes feverish about once in every ten days, his liver seems to be out of order judgino- from the orange color of the membranes of the eye, but he manages to do his work so relapse after relapse is apt to occur before the veterinary officer sees the patient. But he, too, has his difficulties to contend with in diagnosis of the disease in these earlier stages. The animal is probably brought to him after the crisis of the relapse, the day when he specially attracts attention of those in charge ; but the disease is characterized by a sudden fall in body temperature after this crisis, and thus the thermometer may give a reading of but 101° F., and the records of four or five successive daily observa- tions may show only slight variations ranging between this point and the normal. It is just at this point, too, that examination of the blood by means of the microscope fails in its diagnostic value, for at this phase of the disease the blood is free from detectable parasites. As a matter of fact, I believe it impossible to diagnose the disease promptly under these circumstances, to distinguish it from simple congestive disorder of the liver. If the observations with our two instruments of precision—the thermometer and microscope—be continued for five days, a diagnosis may be given ; if for ten da^s, a positive statement as to the presence or absence of the disorder may he made without the possibility of error. This exactitude in diagnosis is a valuable feature in the clinical history of the disease; it may best be attained by use of the thermometer and thermo- graphic charts and by detection of spirilloids in the blood by means of the microscope • but it is important to note that, in the absence of these instruments or of skill to use them, the number of beats of the pulse if recorded on a chart daily for ten days and a mark made against the tracing whenever the animal seems very feverish (as indicated by heat of mouth, dullness and thirst), the periodicity of the disease will be recognized and a very fair approximate diagnosis may be made. But from the very nature of the disease it is necessary that time be allowed for the diagnosis except when a drop of blood under the microscope is found to contain the characteristic organisms then the nature of the main disease can be no longer doubtful, but there is always the possi- bility of the case being a complicated one. During the access of the fever the membranes of the nose, mouth, and eyes are generally yellow (especially the conjunctivse), but in the intervals they become markedly pale, that of the mouth seems to have scarcely any blood in its veins, occasionally the epithelium of the gums inside of the lips, or tongue undergoes degeneration and separates from the deeper part of the membrane, leaving superficial circumscribed ulcers. A favorite position for these is on the margin of the lower lip, and I have seen them arranged symmetrically in pairs here and on the tip of the tongue. These must not be confounded with spear- grass ulcers, wounds received from the bit or from balling iron, twitch, or drenching bottle. It is not always possible to determine whether ulcers in the mouth of a patient are from injury or the result of circumscribed degeneration of the epithelium from the action of disease. Occasionally ulcers of this kind appear on the Schneiderian membrane where the epithelial debris remains as a yellow scab for a day or two and is then washed away by mucus ; the earliest appearance of these ulcers in the nose is as though the membrane had been grazed and blood were slowly oozing; they rapidly disappear and the general character of the membrane again becomes normal. I have noted in the mouth, eyelid, and labium vulvae large ulcers which looked as though the result of injury ; they generally healed freely when treated with carbolic oil. In one or two cases I have noted an eruption of spots on the skin, especially that of the muzzle, apparently resembling in their essential nature those of the mouth and nostril, Q]]dema of the mucous membranes sometimes occurs ; it is most frequent in the case of the conjunctiva, making the eyelids thick and the eyeball to seem sunken • the presence of this symptom renders it difficult to cause protrusion of the haw in the usual way and to determine whether or no petechias are present. In some cases the conjunctiva becomes bladder-like and bulges with effusion; one or both eyes and one](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b24749278_0064.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)