Report of the Royal Commission on the care and control of the feeble-minded, Volume VIII.

- Great Britain. Royal Commission on the Care and Control of the Feeble-minded.

- Date:

- 1908

Licence: In copyright

Credit: Report of the Royal Commission on the care and control of the feeble-minded, Volume VIII. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by Royal College of Physicians, London. The original may be consulted at Royal College of Physicians, London.

320/552 (page 288)

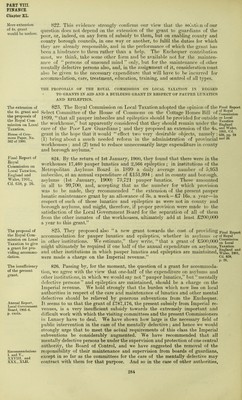

![FINANCE. Chapter XL. The “ Block ” ^ant—contd. Report of the Royal Commisf^ion on Local Taxation, 1901, p. 77. minimum expenditure, the rate should be so fixed that it will not produce more than 3s. 6d. per head of the population in any appreciable number of unions, otherwise those unions would receive no grant. This condition would be satisfied by a rate of 4d. in the £,, since there are few unions in which this rate on assessable value would produce more than 3s. 6d. per head. On the other hand, to throw upon the localities less in any case than one-third of the expenditure would be inconsistent with prudence, and a rate of 4d. in the £ would produce about one-third of the expenditure in the more economical of the poorest unions. Consequently it is suggested that the standard rate should be fixed at 4d. in the “The grant will then be divided into two parts, to correspond with the division of the expenditure, and from the first and larger part will be distributed to each area the product of 3s. fid. per head of the population after the deduction of the product of the 4d rate on the assessable value. The minimum expenditure would thus entail a rate of 4d. in the £ in every union. The second and smaller part of the grant would consist of one-third of the expenditure incurred in excess of the minimum (expenditure hese means the expenditure of the financial year preceding legislation, “standardised” in the manner prescribed in the Irish Local Government Act, 1898 [Sec. 49])—thus leaving the remaining two-thirds of the expenditure above 3s. fid. per head to be met from local sources. The grant might be fixed for a period of years, and this limit (coupled with the administrative safeguards to which I refer presently) would prevent aid being given to expenditure which is not necessary, and retain the inducements to real economy. As a further safeguard it would probably be desirable that no union should receive more than two-thirds of its expenditure, in case such a contingency should arise when revised figures of population, valuation, and expenditure are available for calculating the grant.” 834. To apply this method then, for the details require close attention, and we repeat the calculation therefore in a rather different form—Suppose 3s. 6d. a head to be taken as the standard of expenditure per head of the popu- lation which is generally applicable. This standard of expenditure is applied to the population of the particular area. That area has, for example, a popu- lation of 10,000. This produces a sum of £1,750. Again, suppose 4d. in the £ to be taken as the standard of assessable value which is generally applicable. This standard assessment is applied to the assessable value of the particular area. The area has an assessable value of £60,000. This jjroduces £1,000. The difference between the general standard of expenditure as applied to the population and the general standard of assessable value as applied to the assessable value of the particular area is the sum payable as a 'primary grant from the Exchequer to the area : £1,750 —£1,000 = £750. In this grant, we equalise rich and poor districts from the point of view of their assessable value in its relation to their standard expenditure. The next process is to regulate the grant that may be made to the area in relation to any excess of expenditure on its part over and above the standard expenditure. The actual expenditure of the area is taken to be, say, £2,500. The standard expenditure we have seen is £1,750. If this be deducted from the other, £2,500 — £1,750 = £750, we have the excess of expenditure. And of tliis, some definite part, it is suggested, should be payable as a secondary grant. Lord Balfour of Burleigh proposes one-third. Accordingly the area would receive £250—one-thir.d of the £750, its excess of expenditure. The total grant would then be: as primary grant, £750; as secondary grant, £250. As the actual expenditure of the area is £2,500, it would have to raise the difference, £2,500—£1,000 {i.e., Z750 + £.^50) = £1,500 from the local rates. The primary and secondary grants taken together would make what Lord Balfour calls the block grant. In this way, when account has been taken of expenditure, the larger the assessable value the less the grant, and vice versa. Adoption of Block ” grant suggested. Recommendation XLI. We have endeavoured to explain the principle of this scheme, as we believe that, if it were generally imderstood, it would, on the financial side of our problem, lead to the application of conditions wliich would tend both to local economy and to fair and legitimate central control. The relative amount of the grant would be settled, according to the standard of expenditure per head of the population and the standard of assessable value agreed upon for a defimite period, such as ten years. It would not vary according](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b28038551_0320.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)