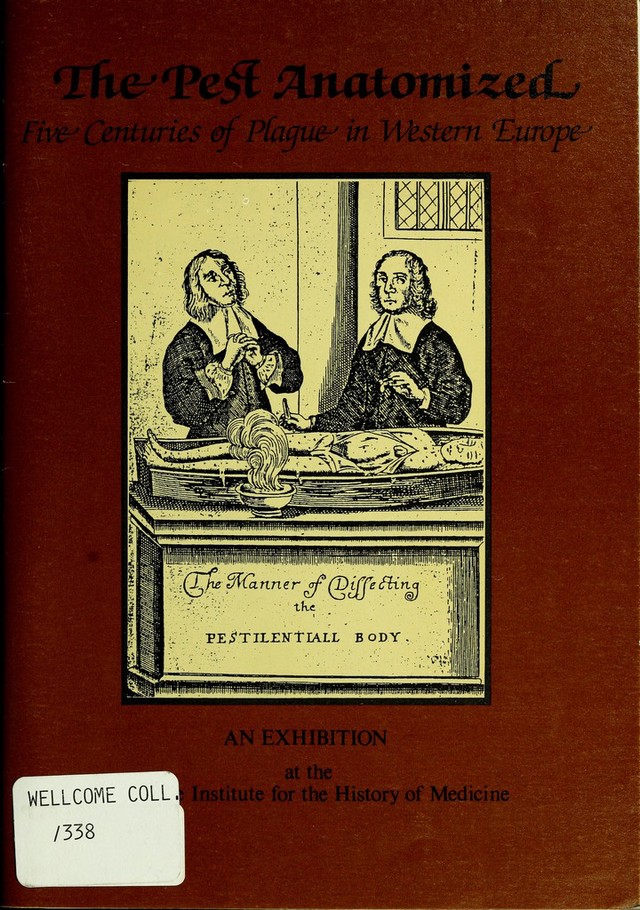

The pest anatomized : five centuries of plague in Western Europe. An exhibition at the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine ... 4 March to 24 May 1985 / [compiled by Richard Palmer and Christine English].

- Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine

- Date:

- 1985

Licence: Attribution 4.0 International (CC BY 4.0)

Credit: The pest anatomized : five centuries of plague in Western Europe. An exhibition at the Wellcome Institute for the History of Medicine ... 4 March to 24 May 1985 / [compiled by Richard Palmer and Christine English]. Source: Wellcome Collection.

19/48 page 9

![Brad well's Physick for the sicknesse, commonly called the plague, London, 1636. Bradwell, the grandson of the famous John Banister, sold many similar preparations, a 'powder of life', 'plague powder' etc. Bradwell was careful to dissociate himself from the 'Mountebancks', whom he instructed to 'goe quack in the country'. Pharmacopoea Londinensis. London, 1618. Theriac was amongst the most highly prized of antidotes. The official pharmacopoeia issued by the College of Physicians of London lists the ingredients of the ancient theriac of Andromachus, and also those of a simpler London theriac, which could be made mainly from local ingredients. The manufacture of theriac. Woodcut published in works by Hieronymus Brunschwig, including his Liber de arte distillandi (Strasbourg, 1512). The manufacture of an electuary as complex and prestigious as the theriac of Andromachus required elaborate procedures. It was normally made in substantial quantities, sometimes by several pharmacists in partnership. Colleges of Physicians and even civic officials were involved in checking the ingredients and supervising procedures. Manufacture could become a public ceremony. Francesco Calzolari of Verona, one of the most respected manufacturers, used to put the ingredients on public display, to the sound of trumpets and drums. Vipers being prepared for medicinal use. Photograph of a woodcut from [Hortus Sanitatis] Le iardin de sant6, TParis, ? 1529). Troches made from vipers' flesh were a central ingredient of the theriac of Andromachus. Bartolomeo Maranta, Delia theriaca et del mithridato. Venice, 1572. Maranta noted that theriac had never failed as an antidote in antiquity, when its virtues were tested in clinical trials on criminals condemned to death. Like other sixteenth century pharmacists, he strove to recover the authentic classical ingredients necessary to perfect the drug, and to make available its remarkable curative properties. Drug jar, for theriac of Andromachus Tin-glazed earthenware, with blue decoration on a white background. Labelled 'Ther. And.'. English, 17th cent. W.M.H.M., inventory number A.643570 (for similar jars, cf. Crellin, fig. 16). Theriac stamp. Venetian, 17th or 18th cent. The stamp was used for labelling theriac containers. It was employed in the Speciaria della Madonna in Campo San Bartolomeo, Venice. The brass relief snows the Madonna and child, with the lion of St. Mark. Venetian theriac was the most prestigious in Europe. W.M.H.M., inventory number A.656705. Drug jar, for mithridatum Tin-glazed earthenware, with blue decoration on a cream background. Labelled 'mitridatium'. Dutch, ?eighteenth cent. W.M.H.M., inventory number A.643554 (Crellin, n. 92, fig. 145). Simon Kellwaye, A defensative against the plague. London, 1593. The medicinal earths, Armenian bole and terra sigillata, were widely used against the plague. Kellwaye included both in his 'pouder to expell the plague and provoketh sweat', along with fragments of precious stones, unicorn's horn, and other simples. -9-](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b20457790_0019.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)