Volume 1

Chemistry, theoretical, practical, and analytical : as applied and relating to the arts and manufactures / by Dr. Sheridan Muspratt.

- Muspratt, Sheridan, 1821-1871.

- Date:

- [1860]

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Chemistry, theoretical, practical, and analytical : as applied and relating to the arts and manufactures / by Dr. Sheridan Muspratt. Source: Wellcome Collection.

77/308 (page 61)

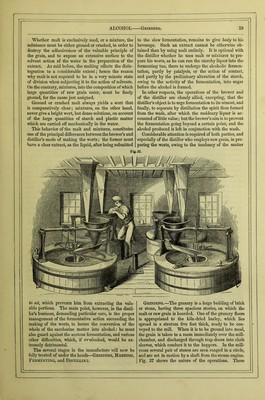

![ALCOHOL ]\lAsniNG. two of the former to one of the latter. K the propor- tion of raw grain be large when compared with that of the malt, it is a general custom to add a quantity of chaff, in order that, when the mashing water has ex- tracted the saccharine and starchy portions, it may be more easily filtered or drawn off. The quantity of malt and grain used at each mash- ing, depends on the size of the distillery; hence no fixed rule can he laid down. In the distilleries in Dublin, the quantity of grist at each brewing varies with circumstances, from eight hundred bushels, the lowest, to two thousand bushels, the largest quantity. In nearly all cases, it is composed of seven eighth- parts of raw or unmalted, and one eighth-part of malted grain. Previous to introducing the malt, a quantity of water, at a temperature between 140° and 150° Fahr., is run into the mash tun, and the ground malt and meal are then added. A number of workmen, with stout wooden spatulas or oars, keeps the mixture in brisk agitation, until the grist is thoroughly moistened, and neither clots nor lumps remain. In the larger establishments, this part of the operation is effected by macliinery, and is much more efficiently performed than by manual labor. The perforated false bottom allows the wort to percolate 'nto the space between it and the true bottom of the tun, from which it is drawn off more easily into the under-backs,—large vessels placed be- neath the mash tun, wherein the worts are collected till pumped into the cooling-backs. Distillers and brewers are more variable in their mode of working than any class of manufacturers who carry on business extensively. In no one operation do they seemingly follow a common rule, each having some favorite plan of a supposed greater merit than others; hence the difficulty of givirig a true and comprehensive detail of these branches. This assertion has been partly demonstrated already, when speaking of the grist; and in the next operation, the mashing, it becomes more manifest. The whole of Uie saccharine and fermentable matters of the grist introduced into the mash tun, is generally extracted in three, always in four mashings at most; but the manner of doing so is different, according to the notions of the manager. At one time, the first, second, and third mashings were evaporated till the mixture ac- quired a density of about 1-05, when it was ready for the fermenting tun, the fourth wash being reserved for extracting fresh quantities of grist. Some employ the water in the first and second extract in such quantities as that the wort will be of a strength fit for fermenting, and the third and fourth wash may be concentrated by evaporation to the proper density, and then added to the preceding; or these dilute solutions may be made of the proper strength by running them on fresh quan- tities of ground malt and grain. Others, again, manage the quantity of water in such a manner that the pro- duct of the first extract will have the density necessary for submitting it to the fermenting vessels. The re- maining three washings are rendered stronger either by evaporation, or mashing with fresh portions of malt or grist. In the latter case, the quantity of water is larger in the first mashing than in the preceding in- 61 stance, where the first two extracts are made of the strength 1'050, which together amount to about twice the volume of grist In Macfarlane and Co.’s distillery at Glasgow, two hundred and sixty himdred-weight of grist, including a sixth or a fourth of malt, are taken for an ordinary mash, and these are put into the mash tun, and about seven hundred and eighty-eight barrels of water— nearly twenty-eight thousand three hundred and sixty- eight gallons—are poured upon them at two stages of the operation. In the Dublin distilleries, about seven-eighths of raw grain are employed. Like the preceding, the first mash is tlie only one let into the fermenting tun, the succeed- ing small worts being kept for the next day’s brewing; and in preparing this wort about five barrels of water are taken to the quarter of grist, hut more if small worts are used; to completely exhaust the grist, about the same amount of water is required for the subsequent mashing. The temperature of the water varies with the quan- tity of malt present; when the malt and raw grain are mixed in the proportion of one of malt to two of grain, the first mashing may be made at a tem- perature of 150° to 160° Fahr., but if the malt and grain be as one to four, six, or nine, then the water should not exceed 145° for the first mashing, in order to prevent the setting of the mass. A longer time is likewise required for the first mashing with a large quantity of raw grain than if it were entirely malt, as the starchy matter of the grain is more difficultly ex- tracted than the saccharine principle which replaces it in the malted grain. From one hour and a half to two hours generally suffice for this operation, where the contents of the mash tub are kept in agitation by machinery, and the proper heat of the water has been attended to; but very often the time occupied may extend to three or more hours. In successful cases, the time required for the wort to clarify, is about one to two hours. As the temperature of the solution becomes lower from contact with the grist, and from the agitation, it is customary not to add the whole of the water employed in the first mash at once, but to retain from half to a quarter of the liquid, which is added, at short intervals, towards the middle of the operation. This serves to keep the heat more uniform, and the work is more effectually accomplished. In the Scotch distillery above mentioned, when the first water at 140° permeates the whole of the grist, the remainder of the seven hundred and eighty-eight barrels is poured in, at a temperature ranging between 175° and 180°, so as to heat the whole contents of the tun to 150°. After the wort has been drawn off into the under- back, and pumped into the coolers, the second sperge is then let in upon the grist remaining in the mash tun, and a similar treatment to the foregoing given to the mash; the time occupied is one hour and a half, and the density of the weak wort is from fifteen to six- teen pounds per barrel. Since the greater part of the saccharine and starchy matters of the grist is extracted in the first affusion.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b28122719_0001_0087.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)