A history of the mathematical theory of probability from the time of Pascal to that of Laplace / by I. Todhunter.

- Isaac Todhunter

- Date:

- 1865

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: A history of the mathematical theory of probability from the time of Pascal to that of Laplace / by I. Todhunter. Source: Wellcome Collection.

548/648 (page 528)

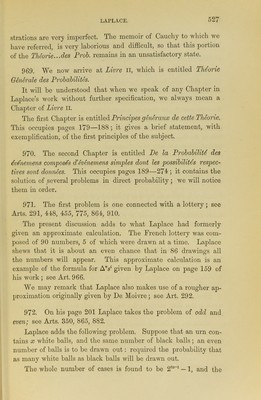

![whole number of favourable cases to be (2a; \x \x — 1; the required probability therefore is the latter number divided by the former. 973. The next problem is the Problem of Points. Laplace treats this very fully under its various modifications; the dis- cussion occupies his pages 203—217. See Arts. 872, 881. We will exhibit in substance, Laplace’s mode of investigation. Two players A and B want respectively x and y points of winning a set of games; their chances of wanning a single game are p and q respectively, where the sum of p and q is unity ; the stake is to belong to the player who first makes up his set: determine the probabilities in favour of each player. Let </> (x, y) denote A’s probability. Then his chance of Avin- ning the next game is p, and if he wins it his probability becomes (f) [x — 1, y); and q is his chance of losing this game, and if he loses it his probability becomes (x, y — 1) : thus cf)(x, y) =pc})(x-l, y)+ qc})(x, y-l) (1). Su]3pose that <£ (x, y) is the coefficient of txTv in the develop- ment according to powers of t and r of a certain function u of these variables. From (1) we shall obtain u — Xcf){x, 0)f — X<}> (0, y) jv + $ (0, 0) = u (pt + qr) — ptX </> (x, 0) f — qrX4> (0, y) rv (2), where X </> {x, 0) f. denotes a summation with respect to x from x — 0 inclusive to x = go ; and X (f> (0, y) rv denotes a summation with respect to y from y — 0 inclusive to y = co . In order to shew that (2) is true we have to observe two facts. First, the coefficient of any such term as tmrn, where neither m nor n is less than unity, is the same on both sides of (2) by virtue of (1). Secondly, on the left-hand side of (2) such terms as t t , wheie m or n is less than unity, cancel each other; and so also do such terms on the right-hand side of (2). Thus (2) is fully established. From (2) we obtain (1 -pt) X(/> (x, 0) f + (1 - gr) X<J> (0, y)tv-4> (°._0); . 1 —pt — qT u =](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b24863026_0548.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)