A manual of chemistry : on the basis of Dr. Turner's Elements of chemistry : containing, in a condensed form, all the most important facts and principles of the science designed for a text book in colleges and other seminaries of learning / by John Johnston.

- John Johnston

- Date:

- 1846

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: A manual of chemistry : on the basis of Dr. Turner's Elements of chemistry : containing, in a condensed form, all the most important facts and principles of the science designed for a text book in colleges and other seminaries of learning / by John Johnston. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the National Library of Medicine (U.S.), through the Medical Heritage Library. The original may be consulted at the National Library of Medicine (U.S.)

65/488

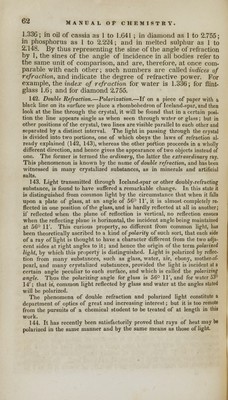

![141. Bodies differ in their power of refracting light. In general, the denser a substance is, the greater is the deviation which it produces. If in figure 14, sulphuric acid were mixed with the water, the ray IC would be refracted to some point between E and G; and if a solid cake of glass were substituted for that liquid, the refracted ray would be bent down to CG. But this is far from universal: — alcohol, ether, and olive-oil, which are lighter than water, have a higher refractive power. Observation has shown it to be a law, to which no exception is yet known, that oils and other highly inflammable bodies, 6uch as hydrogen, diamond, phosphorus, sulphur, amber, olive- oil, and camphor, have a refractive power which is from two to seven times greater than that of incombustible substances of equal density. But whatever may be the refractive power of bodies in relation to each other, refraction is always governed by the two following laws, discovered in 1618, by Snell, though usually ascribed to Descartes. 1. The direction of the incident and refracted ray is always in a plane perpendicular to the surface common to the media. 2. The sine of the angle of incidence and the sine of the angle of refraction are in a constant ratio for the same media. Fig ]5 The first law is similar to the u first law of reflection already ex- -v. plained(142.) To explain the second ^\ law, let ABE, fig. 15, be a vertical \ section of a refracting medium, \ PP' the perpendicular to it, IC a ] ray of light incident at C, and CE jB the refracted ray Then ICP is / the angle of incidence, and ECP' \ / the angle of refraction. Also from VV/ C as a centre, with any radius CI, Ee and in the plane of the ray ICE, draw a circle; and from the points I and E, where the course of the ray cuts the circle, let fall la, Ec at right angles to PP. Then may la be considered the sine of the angle of incidence, and Ecthe sine of the angle of refrac- tion. The second law denotes that these lines are for each substance in a constant ratio, whatever may be the direction of the incident ray In the figure the sine of the angle of refrac- tion is to the sine of the angle of incidence as 1 to 2; and this ratio being once determined, each ray must conform itself to it, so that any angle of incidence being given, the direction of the refracted ray may be foretold. Thus, if ?C be a second ray incident at C, of which ib is the sine of the angle of inci- dence, the ray will be bent into such a course, that ed shall be to ib as 1 to 2. This ratio is nearly that observed in glass made of one part of flint to three of oxide of lead. In common flint-glass, the ratio is nearly as 1 to 1.6; in water it is as 1 to 0](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21133840_0065.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)