A manual of diseases of the nervous system / by Sir W.R. Gowers ; edited by Sir W.R. Gowers and James Taylor.

- William Richard Gowers

- Date:

- 1899

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: A manual of diseases of the nervous system / by Sir W.R. Gowers ; edited by Sir W.R. Gowers and James Taylor. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by King’s College London. The original may be consulted at King’s College London.

672/720 (page 650)

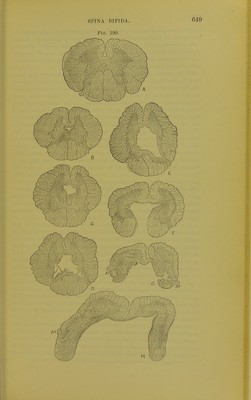

![SPINAL CORD. according as the sac contains only the spinal membranes (meningocele), the spina] cord as well as the membranes (meningomyelocele), or the latter distended by enlargement of the central cavity (syringo- myelocele). These are the chief classes; they do not, indeed, exhaust the rarer forms, but to take full cognizance of Uicsc would entail a very complex list of varieties.* Of the several forms, that without an external tumour has been least frequently met with, although it is probable that a knowledge of the significance of the growth of hair in the lumbar region would lead to the detection of this state in many cases in which it is now undiscovered. Putting this form aside, simple meningocele and syringomyelocele are both rare; the common form is meningo- myelocele, in which the cord, altered or intact, extends within the sac. The Clinical Society's Committee found that this was the condition in 62 per cent, of the cases in which there was an external tumour. The lower part of the spinal cord is generally adherent to the posterior wall of the sac, where its traction often causes a depression on the stirface, always at the membranous area, which, as already mentioned, is generally to be observed in the upper portion. The cord may again become free, and extend downwards in the cavity, or it may be flattened, expanded, and lost in the wall, of which its tissue really forms an inner layer. In this layer there is no distinction of grey and white substance. In either case the lower nerves arise in the wall, and pass, first in this, and then forwards, across the cavity, to their fora- mina of exit. The arachnoid always extends into the sac, and the fluid is that contained within the subarachnoid space; sometimes there is an external opening from which the fluid flows. As a rule, the central canal of the cord is not continuous with the sac ; and it may be closed, even in the condition of syringomyelocele,'in which the canal is dilated. In other cases the canal opens into the cavity, sometimes by only a small aperture, even when the lower part of the cord expands into the wall, and the nerves course along the wall in a layer continuous with the arachnoid and superficial to the membrane that represents the cord-tissue from which they arise. As stated, ordinary syringomyelia may exist in the upper part of the cord. The extension of the cord in the wall of the sac probably indicates a developmental defect similar to that of the bony canal; in the lumbar region the primitive canal has failed to close, so that the cord is open posteriorly, and the two posterior columns may even be far apart, or the cord may even be applied, in the form of a thick or thin lamina, to the wall of the sac. An instructive although rare example of the involvement of the cord in the developmental effect is shown in Fig. 190, which illus- trates also the manner in which the latter may involve in some degree the whole cord. In the cervical region the grey commissure is unusually large, and the canal is cruciform, a shape which it presents * Several other varieties are enumerated by Bland Sutton (loc. cit.).](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21294483_0678.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)