Text-book of botany : morphological and physiological / by Julius Sachs ; translated and annotated by Alfred W. Bennett ; assisted by W.T. Thiselton Dyer.

- Date:

- 1875

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Text-book of botany : morphological and physiological / by Julius Sachs ; translated and annotated by Alfred W. Bennett ; assisted by W.T. Thiselton Dyer. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. The original may be consulted at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

100/880 page 84

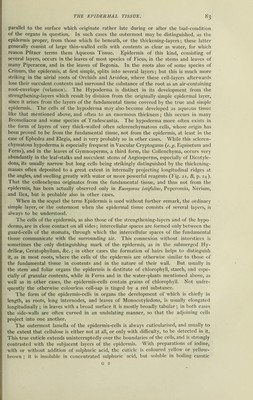

![potash. In submerged organs and roots it is very thin, difficult to be seen immediately, but rendered visible by iodine and sulphuric acid. The true cuticle is much thicker in aerial stems and leaves; it may be obtained in them even in large lamellae by decay or solution of the subjacent cells in concentrated sulphuric acid. In many cases, and especially in stout leaves and internodes, the outer wall of the epidermis-cells lying beneath the cuticle is strongly often enormously thickened; while the inner-walls re- main thin, the lateral walls are usually strongly thickened outwardly, becoming inwardly suddenly thinned. The thick portions of the wall are usually differentiated into at least two shells; — an inner thin shell, immediately surrounding the cell-cavity, shows the reactions of pure cellulose, while the epidermal layers lying between it and the cuticle are more or less cuticularised, and the more so the nearer they lie to the cuticle. Not unfrequently these layers of cuticle extend downwards in the thick part of the side-walls, in which case the middle lamella sometimes behaves like the true cuticle, with which it is in contact on the outside. Like the isolated cells of the cuticle (pollen- grains, spores), the epidermis has also a tendency to form projecting lumps, knots, ridges, &c., but they almost always remain very insignificant, and are best seen on a superficial view; as, for example, in many delicate petals (cf. sect. 4, (e)). According to the recent researches of De Bary, particles of wax are deposited in the substance of the cuticular layers of the epidermis which cannot be seen on section, but separate in the form of drops when warmed to about ioo° C. This deposit of wax (often combined with resin) is one of the causes which protect the aerial parts of plants from becoming moistened with water. But very frequently the wax extends in an unexplained manner over the cuticle, and becomes deposited there in different forms, forming the so-called bloom on fruits and some leaves, or as a continuous shining coating, which is reformed on young organs after being wiped off, and in ripe fruits of Benincasa cerifera (the wax-cucumber) appears again long after maturity. De Bary distinguishes four principal forms of this wax-coating. The bloom or gloss which is easily wiped off consists of small particles of two forms:—(1) of quantities of delicate minute rods or needles, e. g. the white-dusted Eucalypti, Acaciae, many Grasses, &c.; or of granules collected into several layers, as in Kleinia fcoides and Ricinus communis; these are aggregated wax-coatings. (2) Simple granular coatings consist of grains iso- lated or touching one another in one layer; this is the most common form, e. g. in Iris pallida, Allium Cepa, Brassica oleracea, &c. (3) Coatings of minute rods consisting of thin, long, rod-shaped particles, bent above or even curl-shaped, and standing perpen- dicularly upon the cuticle, e. g. Heliconia farinosa and other Musaceae, Cannaceae, Saccha- rum, Benincasa cerifera, leaves of Cotyledon orbicularis. (4) Membrane-like layers of wax or incrustations; (a) as a gritty glazing in Sempervivum, Euphorbia Caput-Medusa, Thuja occidentalis ; (b) as thin scales, in Cereus alatus, Opuntia, Portulaca oleracea, Taxus baccata; (c) as thick connected incrustations of wax, which sometimes permit a finer internal structure to be recognised, similar to the striation and stratification of the cell-wall: Euphorbia canariensis, fruits of species of Myrica, stems of Panicum turgidum. On the stem of the Peruvian wax-palms, especially of Ceroxylon andicola, these incrus- tations attain a thickness of 5 mm.; those on the stem of Chamcedorea Schiedeana are thinner, but of similar structure. According to Wiesner (Bot. Zeitg. p. 771, 1871), these flakes of wax consist of doubly refractive four-sided prisms standing perpendi- cularly close to one another. Hairs1 are products of the epidermis; they originate from the growth of single epidermis-cells, and are present in most plants in large numbers ; when they are 1 A. Weiss, Die Pflanzenhaare, in vols. IV and V of the Bot. Untersuchungen aus dem phys. Laborat. by Karsten, 1867.—J. Hanstein, Bot. Zeitg. p. 697 et seq., 1868.—Rauter, Zur Entwickel- ungsgeschichte einiger Trichomgebilde. Wien 1871. [See also J. B. Martinet: Organes de secretion des v£getaux. Ann. des Sci. Nat. Fifth series, vol. XIV, 1871.]](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21981437_0100.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)