Text-book of botany : morphological and physiological / by Julius Sachs ; translated and annotated by Alfred W. Bennett ; assisted by W.T. Thiselton Dyer.

- Date:

- 1875

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Text-book of botany : morphological and physiological / by Julius Sachs ; translated and annotated by Alfred W. Bennett ; assisted by W.T. Thiselton Dyer. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. The original may be consulted at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

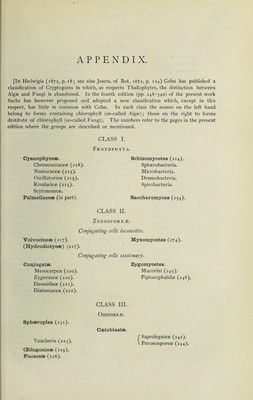

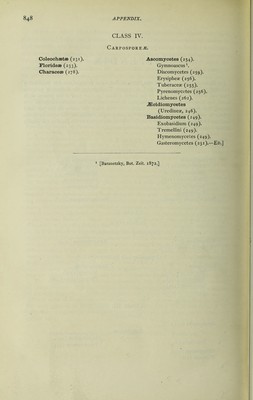

861/880 page 845

![represent the ancestors of the Vascular Cryptogams, and from this branch of the tree the Ferns, Equisetacese, Ophioglossacese, Rhizocarpese, and Lycopodiacese, would proceed as branches which themselves further ramify. Where the branch is given off for the heterosporous Vascular Cryptogams would be situated the primitive forms of Phanerogams, beginning with the Cycadeae, and producing by further ramifications the Conifer®, Monocotyledons, and Dicotyledons1. There is still much uncertainty in this plan, but the greater the progress made by a severe method of investigation and with the light of the theory of descent, the more nearly will it be possible to build up the family-tree and to give it a distinct form. The theory of descent requires that the various forms of plants must have arisen at different times, that the primitive forms of the separate classes and groups existed at an earlier period than the derived ones; and palaeontological research, although at present it has but a very small amount of material at its disposal, supports this view. In the same manner it is a necessary consequence of the theory that each plant- form must have originated at a definite spot, that it must have spread gradually more widely from that spot, that its change of locality in the course of generations must have depended on climatic conditions, the competition of rivals, &c., and that its distribution must have been impeded by hindrances or assisted by means of transport2. The geographical distribution of plants has already determined in the case of many forms the spots on the surface of the earth or centres of distri- bution from which they gradually spread; it has shown how the distribution has been hindered sometimes by climate, sometimes by chains of mountains, sometimes by seas; how more recently formed islands have been peopled by the plants from the neighbouring continents which have become the ancestors of new species3; how some species when transported to a new soil (as European plants in America and vice versa) have sometimes carried on a successful struggle for existence with the native plants and have increased enormously. In the distribution of plants at present existing, as for instance Alpine plants, it is possible to recognise the influences of the last great geological changes, of the entrance and disappearance of the glacial epoch and of earlier periods. 1 [In the fourth edition of his 1 Lehrbuch,’ recently published, Sachs has united Algae and Fungi into one group (see Appendix, p. 847). He has also withdrawn the pedigree of the vegetable king- dom sketched in the text, and has substituted for it (p. 918) the following remarks :— ‘ Frequent attempts have been made to draw up such a so-called “ genealogical tree” either for the whole or some part of the vegetable kingdom. Up to the present time these attempts have not proved very satisfactory. Our knowledge of the true relationships is still very imperfect; too much room is consequently left for fanciful speculation and the influence of subjective impressions. I shall content myself therefore with pointing out that in drawing out such a genealogical tree the closest attention must be paid to the simplest existing forms of the different types or classes ; the relationship to the common primitive parent-forms will reveal itself most distinctly in these. From each of these simplest forms, however slightly different, a ramifying series may be derived ; variation, proceeding independently in each series, will separate the series themselves still further ; and the most perfect forms of the different types will therefore differ the most widely from one another.’—Ed.] 2 Kemer has given an illustration of what can be accomplished in this direction in the rela- tionships, geographical distribution, and history of the species of Cytisus from the primitive form Tubocytisus, in his pamphlet Die Abhiingigkeit der Pflanzengestalt von Klima und Boden; Inns- bruck, 1869. 3 See Dr. Hooker, On Insular Floras, Gardener’s Chronicle, Jan. 1867 ; Ann. des sci. nat. 5th series, vol. IV, p. 266.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21981437_0861.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)