Chinese clay figures. Pt. 1, Prolegomena on the history of defensive armor / by Berthold Laufer.

- Berthold Laufer

- Date:

- 1914

Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Chinese clay figures. Pt. 1, Prolegomena on the history of defensive armor / by Berthold Laufer. Source: Wellcome Collection.

18/380 (page 84)

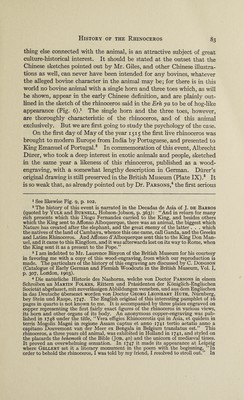

![student of the anatomy of the rhinoceros, it is impossible to assume that he had ever seen the animal. This fact is quite certain, for it is known that the King of Portugal despatched the animal to the Pope, and that it was drowned off Genova when the vessel on board which it was being carried was foundered. The only supposition that remains, therefore, is that some one of Lisbon near King Emanuel must have sent on to Diirer a rough outline-sketch of the novel and curious creature, which was im¬ proved and somewhat adorned by the great artist. But to what sources did he turn for information on the subject? Naturally to that fountain¬ head from which all knowledge was drawn during that period, the au¬ thors of classical antiquity. The fact that Diirer really followed this procedure is evidenced by the very de¬ scription of the animal, which he added to his sketch, and in which he reiterates the story of the ancients regarding the eter¬ nal enmity and struggle of rhinoceros and elephant.* 1 The most curious feature about Diirer’s rhinoceros is Marble Relief of Two-Horned Rhinoceros in Pompeii . (from O. Keller, Antike Tierwelt). that, besides the hOTO On Fig. 3. 1748 it reached Augsburg where Johann Ridinger made a drawing and etching of it with the title as stated (L. Reinhardt, Kulturgeschichte der Nutztiere, p. 751, Miinchen, 1912). The rhinoceros is a subject which for obvious reasons has seldom tempted an artist. It should be emphasized that no artist has ever made even a tolerably good sketch of it, and that only photography has done it full justice. 1 According to the tales of the ancients, the feuds between the two animals were fought for the sake of watering-places and pastures; and the rhinoceros prepared it¬ self for the combat by sharpening its horn on the rocks in order to better rip the arch¬ enemy’s paunch which it knows to be its softest part (compare Diodor, i, 36; Aelian, Nat. animalium, xvn, 44; Pausanias, ix, 21; and Pliny, Nat. hist., viu, 20: alter hie genitus hostis elephanto cornu ad saxa limato praeparat se pugnae, in dimicatione alvum maxime petens, quam scit esse molliorem). The same story is still repeated by Johan Neuhof (Die Gesantschaft der Ost-Indischen Gesellschaft [1655—57], p. 349, Amsterdam, 1669) in his description of the Chinese rhinoceros, which is based on classical, not Chinese reports: “ It makes permanent war on the elephant, and when ready to fight, it whets its horn on stones. In the struggle with the elephant it always hits toward its paunch where it is softest, and when it has opened' a hole there, it desists, and allows it to bleed to death. It grunts like a hog; its flesh eaten by the Moors is so tough that only teeth of steel could bite it.” The Brahmans allowed the flesh of the rhinoceros to be eaten as a medicine (M. Chakravarti, Animals in the Inscriptions of Piyadasi, Memoirs As. Soc. of Bengal, Vol. I, p. 371, Calcutta, 1906); according to al-Berunl (Sachau, Alberuni’s India, Vol. I, p. 204), they had the privilege of eating its flesh. Ctesias stated wrongly that the flesh is so bitter that it is not eaten.](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b31362266_0018.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)