Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Hand-book of physiology / by W. Morrant Baker and Vincent Dormer Harris. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. The original may be consulted at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

45/930 (page 17)

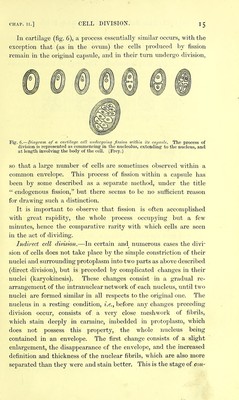

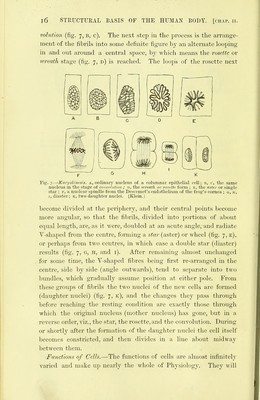

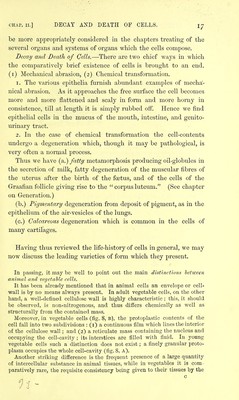

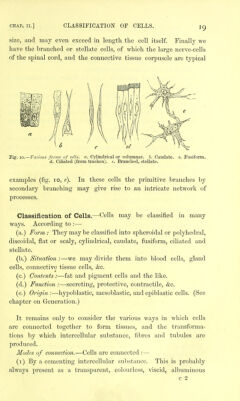

![CHAP. II.] DECAY AND DEATH OF CELLS. be more appropriately considered in the chapters treating of the several organs and systems of organs which the cells compose. Decay and Death of Cells.—There are two chief ways in which the comparatively brief existence of cells is brought to an end. (i) Mechanical abrasion, (2) Chemical transformation. 1. The various epithelia furnish abundant examples of mecha- nical abrasion. As it approaches the free surface the cell becomes more and more flattened and scaly in form and more horny in consistence, till at length it is simply rubbed off. Hence we find epithelial cells in the mucus of the mouth, intestine, and genito- urinary tract. 2. In the case of chemical transfonnatioii the cell-contents undergo a degeneration which, though it may be pathological, is very often a normal process. Thus we have (a,.) fatty metamorphosis producing oil-globules in the secretion of milk, fatty degeneration of the muscular fibres of the uterus after the birth of the foetus, and of the cells of the Graafian follicle giving rise to the corpus luteum. (See chapter on Generation.) (b.) Pigmentary degeneration from deposit of pigment, as in the epithelium of the air-vesicles of the lungs. (c.) Calcareous degeneration which is common in the cells of many cartilages. Having thus reviewed the life-history of cells in general, we may now discuss the leading varieties of form which they present. In passing, it may be well to point out the main distinctions hetween animal and vcfjetahle cells. It has been already mentioned that in animal cells an envelope or cell- wall is by no means always present. In adult vegetable cells, on the other hand, a well-defined cellulose wall is highly characteristic ; this, it should be observed, is non-nitrogenous, and thus differs chemically as well as structurally from the contained mass. Moreover, in vegetable cells (fig. 8, b), the protoplastic contents of the cell fall into two subdivisions : (i) a continuous film which lines the interior of the cellulose wall; and (2) a reticulate mass containing the nucleus and occupying the cell-cavity ; its interstices are filled with fluid. In young vegetable cells such a distinction does not exist; a finely granular proto- plasm occupies the whole cell-cavity (fig. 8, A). Another striking difference is the frequent presence of a large quantity of intercellular substance in animal tissues, while in vegetables it is com • paratively rare, the requisite consistency being given to their tissues by the](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21906300_0045.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)