Licence: Public Domain Mark

Credit: Hand-book of physiology / by W. Morrant Baker and Vincent Dormer Harris. Source: Wellcome Collection.

Provider: This material has been provided by the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh. The original may be consulted at the Royal College of Physicians of Edinburgh.

61/930 (page 33)

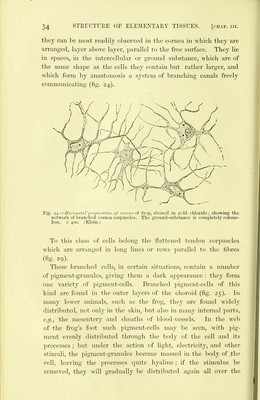

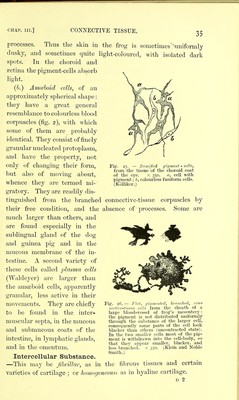

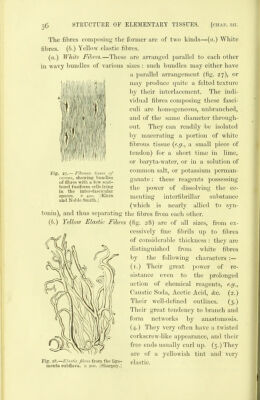

![CHAP. III.] THE CONNECTIVE TISSUES. 23 in the deeper layers. The various stages of its growth and de- velopment can be -well seen in a section of any laminated epithe- lium, such as the epidermis. Th.e Connective Tissues. This group of tissues forms the Skeleton with its various con- nections—bones, cartilages, and ligaments—and also affords a supporting framework and investment to various organs composed of nervous, miiscular, and glandular tissue. Its chief function is the mechanical one of support, and for this purpose it is so inti- mately interwoven with nearly all the textures of the body, that if all other tissues co\ild be removed, and the connective tissues left, we should have a wonderfully exact model of almost every organ and tissue in the body, correct even to the smallest minuticB of structure. Classification of Connective Tissues.—The chief varieties of connective tissues may be thus classified :— I. The Fibrous Connective Tissues. A.—Chief Forms. a. Areolar. h. White fibrous. c. Elastic. B.—Special Varieties. a. Gelatinous. b. Adenoid or Retiform. c. Neuroglia, d. Adipose. II. Cartilage, III. Bone. All of the varieties of connective tissue are made up of two parts, namely, cells and intercellular s^ihstance. Cells.—The cells are of two kinds. (a.) Fixed.—These are cells of a flattened shape, with branched processes, which are often united together to form a network: D](https://iiif.wellcomecollection.org/image/b21906300_0061.jp2/full/800%2C/0/default.jpg)